Note: This post is 3460 words--about a fourteen minute read.

Several presidential candidates have been in favor of the gold standard including Ron Paul in 2012 and Rand Paul and Ted Cruz in 2015. In response, Megan McArdle, explained why almost all economists agree that the gold standard is a terrible idea. McArdle describes herself as a libertarian, but whereas the gold standard is particularly popular among libertarians, she favors Milton Friedman’s version of libertarianism. Friedman strongly advocated that monetary policy–the quantity of money, its value (inflation rate), and its price (interest rate)–should be determined by a government-run central planning agency (the Fed) and not be left up to private markets. McArdle:

Money is a mysterious thing. It is a store of value, it is a medium of exchange. It is [a unit of account, which] in a fiat currency economy, [is] worth only what people think it is worth, and what they think it is worth can be oddly affected by what they think it may be worth in the future, resulting in self-fulfilling feedback loops (at least in the short term). Even in non-fiat currencies, such as the gold standard, the value of the underlying asset can be changed by rising (or shrinking) demand for money. Economists studying this fascinating topic tend to suffer from migraines as they suffer from all the mysterious–hell, nearly mystical–attributes of money.

However, over the last fifty years, economists have settled on some very broad areas of consensus. The first is, as famous libertarian monetary economist Milton Friedman wrote, “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”. When the supply of money outstrips the demand, prices rise. And this is by no means limited to fiat currencies; see the great Spanish inflation of the 16th & 17th centuries, thanks to the steady influx of gold from the New World. Or check out the price of basic commodities in mining towns during the Gold Rush, when all anyone had was gold.

The second is that a little bit of inflation is okay–possibly even beneficial, since it helps the economy to overcome the problem of sticky wages when the relative value of labour has fallen. But a lot of inflation is very, very bad. …[For every] economy that has had inflation… above the double-digit mark; the higher the inflation, the worse the economy did. The feeling that the currency will experience an unpredictable amount of inflation dampens the willingness of the citizens to save and invest, which is why so many third-world loans are denominated in dollars.

The third is that deflation is also bad, and at the lower percentage values, often even worse than inflation. This surprises/offends/meets with the frank disbelief of many “sound money” types, who think that, barring local shortage, in an ideal world everything ought to cost the same or less than it did when Grandpa was a boy. (These sorts of opinions are cemented further by the fact that Grandpa, who is often the source of them, is usually living on a fixed income, and therefore feels that he would make out better in a deflationary economy.) The problem is, deflation does rather devastating things to anyone who has debt, since they now have to repay what they borrowed in more expensive dollars. Deflation means that, thanks to the abovementioned sticky wages, the economy has to deal with demand shocks by lowering output. Deflation can result in what’s known as a liquidity trap, a concept pioneered by liberal economist John Maynard Keynes and best elucidated by liberal economist Paul Krugman… Deflation is what made the Great Depression so memorable. Deflation is so bad that almost everyone agrees that moderate inflation… is better than risking even a small amount of deflation.

Advocates of a gold standard dispute this. They argue that America experienced a long, slow deflation throughout most of the 19th century, without anyone getting hurt. What they neglect to mention is that people did get hurt, repeatedly, in the period’s awful financial contractions. …It’s pretty clear that recessions were longer and deeper than they are now.

This is not only due to the gold standard; the era’s primitive financial system and its approach to financial regulation, which often ranged between lighthearted and foolhardy, also played substantial roles. But the gold standard also has to stand up and take a bow. There’s a strong correlation, for example, between how long a country hewed to the gold standard, and how badly it suffered from the Great Depression.

The gold standard cannot do what a well-run fiat currency can do, which is tailor the money supply to the economy’s demand for money. The supply of gold grows–or not–depending on how much of the stuff is mined. Demand also fluctuates for non-economic reasons; gold has uses besides being money, like industrial components and jewelry.

The lone advantage of a gold standard–and it is a real advantage–is that it prevents governments from inflating the currency. The problem is, this is only moderately true. The government, after all, can always modify its gold standard…

As James Hamilton has pointed out, gold-backed currencies, like all money with a fixed exchange rate, are subject to speculative attacks whenever the government’s financial position looks weak. Such speculative attacks often require punitive economic measures to fight off, which is one of the reasons that America suffered so nastily from the Great Depression–it raised interest rates in the middle of a recession in order to defend the credibility of its currency.

Also, since devaluations tend to produce sharp changes in the values of currencies, rather than smooth appreciations or declines, the economic dislocations are magnified. Imagine you’re a company with a contract denominated in dollars. If the value of the dollar gradually declines, you lose a little, but not too much, since you periodically renew the contract, giving you time to adjust the amounts. If, on the other hand, the devaluation pressure builds up over a period of years, and then all at once the government has to devalue by 20%, you end up badly hurt. You might go out of business. Now multiply that all across the country, and you can see why recessions used to last for years.

[In actuality, the most important issue for businesses is not the rate of inflation, but how predictable inflation is. Businesses can adjust contracts by padding future prices to cope with inflation if the inflation rate is stable over time. It is unexpected changes in inflation that cause problems and the gold standard causes terribly unpredictable inflation.]

In short, you don’t get anything out of a gold standard that you didn’t bring with you. If your government is a credible steward of the money supply, you don’t need it; and if it isn’t, it won’t be able to stay on it long anyway. (See Argentina’s dollar peg). Meanwhile, the limitations on the government’s ability to respond to fiscal crises, the necessity of defending against speculative attacks in times of crises, and the possibility of independent changes in the relative price of gold, make your economy more unstable. It’s a terrible idea, which is why there are so few economists willing to raise their voices in support of it.

In 2011, many Americans wished to return to the gold standard because they were worried about high inflation that never came because the Fed kept inflation low. In fact, the Fed kept it too low. Still some state governments like North Carolina were so scared about inflation they were even discussing plans to print new forms of money based on the gold standard:

Cautioning that the federal dollars in your wallet could soon be little more than green paper backed by broken promises, state Rep. Glen Bradley wants North Carolina to issue its own legal tender backed by silver and gold. The Republican from Youngsville has introduced a bill that would establish a legislative commission to study his plan for a state currency.

Matt Yglesias noted that

A similar measure already passed in Utah. But this reflects, among other things, a fundamental misunderstanding of the relationship between currency and promises. It’s actually a gold-backed currency that’s backed by nothing but promises. When America was on the gold standard, that meant that the government promised to give you such-and-such an amount of gold in exchange for a dollar. When FDR came into office, he decided the government needed expansionary monetary policy so he changed the price of gold. Under the Bretton Woods system, similarly, the government’s promise to convert dollars to gold lasted a few decades and then it went away. It’s a gold standard that represents a government promise that can (and will) be broken. Fiat currency is a government that’s being honest with you. It’s not pretending the money is anything other than what it is.

The practical response for Americans who question the forward-looking strength of the US dollar is just to buy another currency. Europe is run almost exclusively by center-right governing coalitions right now, so you can trust your money to them. Or maybe since all Europeans are socialists by definition you’d prefer to trust your money to the Canadian or British governments. You can buy Korean won or Australian dollars or Brazilian reals. You can even go out and buy actual bars of gold. …But whatever you do, don’t entrust your money to promises by the North Carolina state government to give you gold in the future. That’s just a sucker move that’s going to leave you get stuck holding the bag next time there’s a budget crisis.

I would not expect a new North Carolina dollar to catch on unless people begin to trust the North Carolina state government more than the US federal government. I certainly don’t. Throughout history, whenever a crisis came, governments suspended the gold standard (or silver standard). The US did it during the revolutionary war, the civil war, WWI, and the great depression. Just to give a sense of how it worked, consider WWI. When the war began in Europe it created a financial crisis that spread to the US, so the US briefly suspended the gold standard in July 1914 to deal with it even though the US had not even entered the war yet. Then when the US financial system stabilized, the gold standard was re-established in December 1914 until September 1917 when the US entered the war and gold exports were banned again. The US resumed the full gold standard in June 1919 until 1933 when the US left the gold standard again and never went back. Gold was still used for setting foreign exchange rates until 1973, but Americans couldn’t exchange dollars for gold after 1933.

The only government that has tried to return to the gold standard in modern times is the Islamic State (ISIS) because Isis had a very hard time getting anyone to trust their government and they are embarrassed that they run so much of their economy using US dollars! Plus, they had an ideological reason in that the gold standard is mentioned in the Koran and ancient Islamic law defined exactly how much gold should be in each coin.

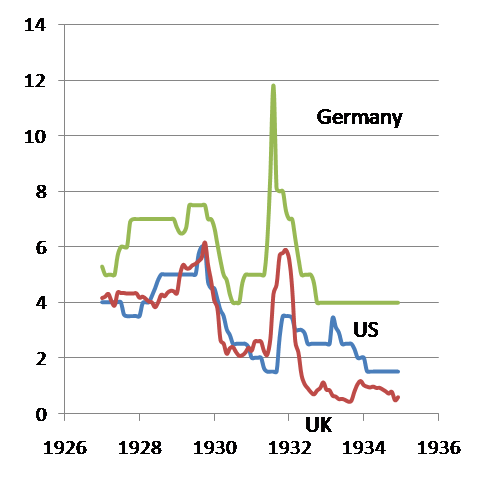

But the gold standard limits monetary policy during recessions and makes recessions worse by causing deflation. Usually countries try to lower interest rates during a severe recession, but several countries dramatically raised a basic interest rate (the discount rate) in 1931 during the Great Depression in a doomed attempt to preserve the gold standard. Paul Krugman created the following graph to show how Germany, the US, and the UK all doubled their interest rates in 1931 because of trying to maintain the gold standard. That crippled these economies and the 12% interest rate in Germany created an economic disaster that helped elect Adolph Hitler in 1932. If Germany had not been on the gold standard, they might have avoided the economic disaster that ultimately produced the disasters wrought by Hitler.

Recessions were much more frequent under the gold standard as you can see on the following graph from Jill Mislinski. There were a lot more shaded vertical bars under the gold standard.

(Note that if you click on the link, you will get an updated version of the graph with the recession shading removed perhaps because it was embarrassing for Dshort which makes money marketing gold purchases to gold bugs and so has ulterior motives to advocate for returning to the gold standard.)

The above graph shows that recessions were longer and more frequent before the Fed was created, and after the gold standard was abandoned in 1933, recessions became dramatically less damaging. It also shows the real value of the dollar over time. One dollar in 1870 was worth twenty times more than a dollar in 2018!

Here is an even longer-term graph from Catherine Mulbrandon:

This graph uses a log scale so that the slope of a line is the rate of growth of prices; in other words the inflation rate. There was very slight deflation for the century before the gold standard was abandoned and modest inflation thereafter. The graph seems to blame the creation of the Fed for higher inflation, but the Fed didn’t create higher inflation. It was WWI that created higher inflation because it created an economic crisis which caused the US to suspend the gold standard, just like what happened during both major prior wars, except that the Fed (intelligently) didn’t allow as much grinding deflation after WWI as had previously happened after the War of 1812 and the Civil War. (The Spanish-American “war” didn’t cause economic problems because it was a super cheap, optional military adventure wherein the US acquired some colonial territory at very little cost. Most wars require at least doubling the military budget, but the Spanish-American “war” was accomplished almost entirely within the normal annual military budget.)

Advocates for the gold standard argue that the two graphs above show that the gold standard is beneficial because it keeps the inflation rate near zero because the value of the dollar stayed fairly constant between the late 1700s and 1933 whereas it lost 95% of its value after then because of abandoning the gold standard.

However, the long-run change in the price level as shown in the graphs above is not at all important for the functioning of the economy. What is important is short-run changes in the price level. That is called inflation and it is important because it is impossible for businesses to plan from year to year if inflation is unstable. Jill Mislinski’s graph of inflation rates tells a more important story by showing the rate of inflation from month to month.

Swings in the inflation rate were more than twice as severe under the gold standard compared with after it was abolished. During the gold standard, the inflation rate commonly swung from -7% to +7%, (a total of 14 percentage points) within only five years of time. After the gold standard was abolished, the inflation rate rarely went negative at all and the positive peaks gradually diminished until 1983 when the “Great Moderation” began. In the four decades since then, inflation has rarely strayed below 1% and rarely risen above 4% (a total range of 3 percentage points).

The only advantage of a gold standard in theory is that if governments stick with the gold standard, it would prevent hyperinflation by limiting monetary expansions somewhat, but they never stick with it during a crisis. And even when governments do stick with the gold standard, there are still bigger swings in inflation than we have seen ever since.

The gold standard officially started in the US in 1900 although gold certificates began circulating as paper money in 1873 and silver started going out of fashion in 1834. Before that, the US and most of Western nations were on the silver standard which looks even worse as a way to avoid inflation and keep prices stable.

(Note that the following graph makes the very brief “classical gold standard” from 1880-1914 look a lot better than the other estimate in the graph above.)

The red arrow in the graph above marks the end of the gold standard during the Great Depression. Although our data quality is poor for the era before fiat money was introduced during the Great Depression, inflation almost certainly reached higher peaks during the silver standard and then the gold standard than it has in the eighty years since. Inflation regularly rose above 13% before fiat money was introduced and has never risen that high since. Even more importantly, there was massive deflation every few years before abandoning the gold standard, and that was frequently accompanied by economic recessions. Under fiat money, we have never had significant deflation and the variance of inflation (the up and down motion) has been MUCH less which helps everyone plan for their economic futures.

The gold standard created more frequent and more severe recessions than we have had with fiat money. A major lesson of the Great Depression is that the gold standard made it Great. Ben Bernanke and Harold James (PDF) found that the sooner each nation abandoned the gold standard the sooner they began their economic recovery from the Great Depression.

The following graph shows the point when each nation left the gold standard using colored lines. Each nation recovered soon after abandoning the gold standard. France had a milder depression than the other nations initially did and so it was able to hold on to the gold standard longer and that helps explain why France didn’t recover as soon as the other nations too. Note that the following graph is not completely accurate because the US did not suspend the gold standard until April of 1933, and what really matters is that the US did not do much to expand the money supply until 1934 which is when the graph shows industrial production finally taking off.

…recovery from the Great Depression does not begin until countries give up on the… gold-standard… Those countries that have central banks willing to print up enough money so that people are willing to spend it–it is when you adopt such policies that your economy begins to recover. If you don’t, you become France, which sticks to the gold standard all the way up to 1937, and never gets a recovery. When World War II begins, Nazi Germany’s production–equal to France’s in 1933–had doubled between 1933 and 1939. French production had fallen by 15%.

If France had ended the gold standard as soon as Germany did, France’s economy would have been much healthier when WWII began and the war might have turned out differently!

The red line in the following graph shows the real price of gold. On the gold standard the value of gold would equal the value of money, so a rise in the gold price would be deflation and a fall in the price of gold would be inflation. There would have been extreme deflation in the 1973 and 1979 on a gold standard and then hyperinflation in the mid 1970s and early 1980s.

That is no way to run a monetary system. Of course, one reason why gold prices took off in the mid 1970s was that it had been illegal for American citizens to own gold bullion until 1974! That bizarre restriction of American freedom had been a legacy of the efforts to maintain the gold standard. Good riddance.

A monetary history of US gold

In response to calls to abolish the Fed and go back to the gold standard, in 2011 the US Congress ordered an analysis of how the gold standard actually worked in US history. This is the conclusion:

U.S. monetary history is not one of steady commitment to gold suddenly abandoned in favor of a fiat standard. Nor were the metallic standards of the 19th and early 20th centuries without paper money or other characteristics abhorrent to some advocates of gold.

First, a genuine gold standard existed only from 1879 to 1933. Prior to that was a bimetallic standard in which silver was dominant from 1792 to 1834, a bimetallic standard with gold dominant from 1834 to 1862, and a fiat money system from 1862 to 1879. After 1933, it was a quasi-gold standard that gradually became a pure fiat standard over the period 1967-1973.

Second, even under the gold standard, the United States had paper money. For most of the time the standard was in operation, this money was issued by [private] banks. Until the Civil War, none of the paper money was legal tender; yet, it circulated [much more than gold]. Moreover, the gold reserve behind paper money was never more than a fraction of the total. This is a common characteristic of metallic standards.

Third, a metallic standard is no guarantee against currency devaluation. The definition of the unit of account can be changed. This was demonstrated by the currency depreciation of 1834, which occurred without ever leaving the standard. Similarly, under a bimetallic standard, depreciation can occur as a consequence of the changing availability of the two metals.

Fourth, even under a metallic standard, the United States issued legal-tender coins that were [alloys of varying purity]. As early as 1853, coins were minted with less silver than called for by the official mint ratio.

Fifth, the Federal Reserve system did not replace the gold standard. The Fed operated under the gold standard for nearly 20 years. A central bank and a metallic standard are not mutually exclusive. Indeed, central banks historically were set up to help the gold standard operate.

Sixth, the classic gold standard ended in 1933; what followed was only a partial—and not full gold standard. A definition of a dollar as a given amount of gold does not make a real gold standard. A genuine metallic standard is one in which the public is able to freely shift gold from exchange to other uses, and paper issued by the government freely convertible into gold. [Gold was only used for foreign exchange settlements to keep exchange rates fixed after 1933.]

Seventh, the final move to a fiat money was not deliberate or purposeful. It occurred by default as [the fixed exchange rates linked] to gold became impossible to maintain. Nor did the final abandonment of gold occur suddenly or cleanly. The United States began to halt its redemptions of dollars into gold for international transactions in 1967 and 1968. The actions of 1971 and 1973 were not the adoption of floating exchange rates and fiat money, but the loss of the ability to redeem dollars at a fixed price. Floating occurred by default.

[…] which is partly controlled by the gold market. Unfortunately for the libertarian purists, even on the gold standard, central bankers and financial regulators could still assert tremendous control over monetary […]

[…] neither the short run (like most modern fiat currencies) or in the long run (like currencies under the gold standard) in which inflation should be close to […]

[…] The problem is that when there is economic growth, people want more money as a store of value and for making more transactions and if the supply of money (gold) is limited, then its price will go up when the money demand goes up. That means deflation. Normally since the Great Depression, the price (value) of money has gone down relative to the value of goods (inflation), but periodic deflation is common under a gold standard. […]

[…] incomes to plummet in a vicious cycle. The reason central banks let the dollar rise was their attempt to maintain the gold standard. Gold has a much less stable (short-run) value than modern fiat dollars and every time gold/money […]