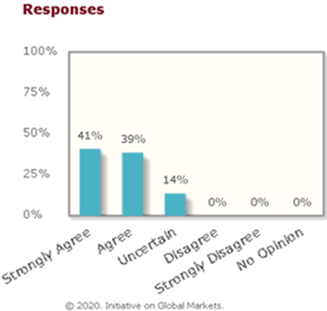

Economists tend to favor relatively free trade in goods and the discipline is even more optimistic about the benefits of the free movement of people. For example, below are some polls of elite economists done by the University of Chicago business school that demonstrate how economists overwhelmingly agree that immigration is good for American innovation, government deficits, and the real income of native-born Americans.

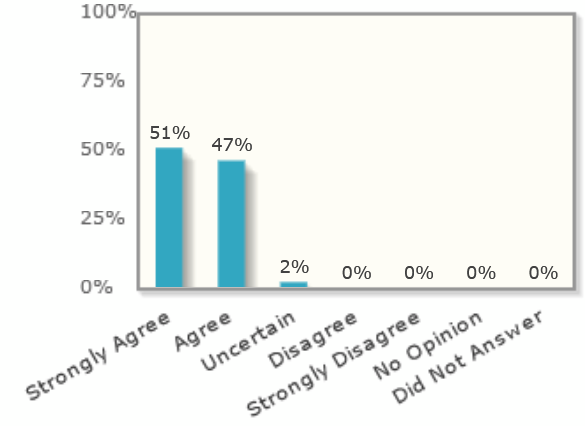

The first poll shows that all economists agreed that it weakened the US in technology when the US government reduced visas for skilled immigrants.

2020: “Even if it is temporary, the ban on visas for skilled workers, including researchers, will weaken US leadership in STEM and R&D.”

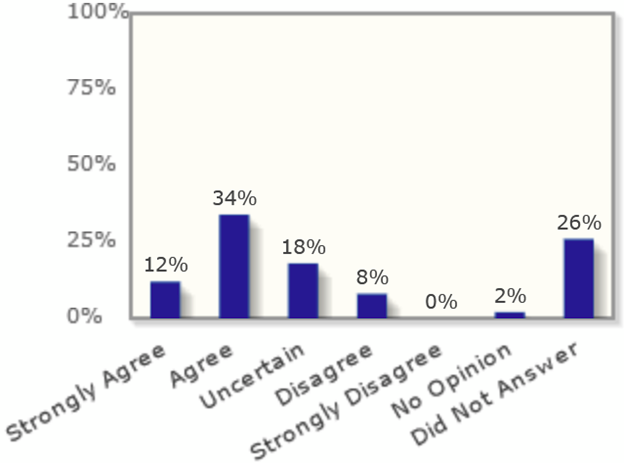

Only 2% of economists polled said that reduced immigration in 2018 would not hurt US innovation:

“Over the past two years, all else equal, the appeal of the US as a destination for immigrants has changed in ways that will likely decrease innovation in the US economy.”

And only 8% of economists thought that immigrants to Europe would get more in welfare benefits than they paid in taxes. And that is in Europe where welfare benefits are much more generous than the US and at a time when Europe was getting flooded by a refugee crisis who typically need more government help than the average US immigrant who was attracted by jobs.

2018: “People who migrated to Europe between 2015 and 2018 are likely — over the next two decades — to contribute more in taxes paid than they receive in benefits and public services.”

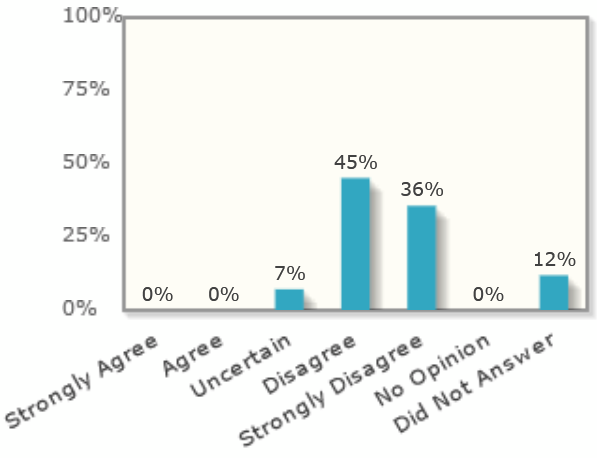

Zero percent of economists think that reducing high-skilled immigrants (who get an H-1B visa) would raise US tax revenues.

2017: “If the US significantly lowers the number of H-1B visas now, expected US tax revenues will rise materially over the next four years.”

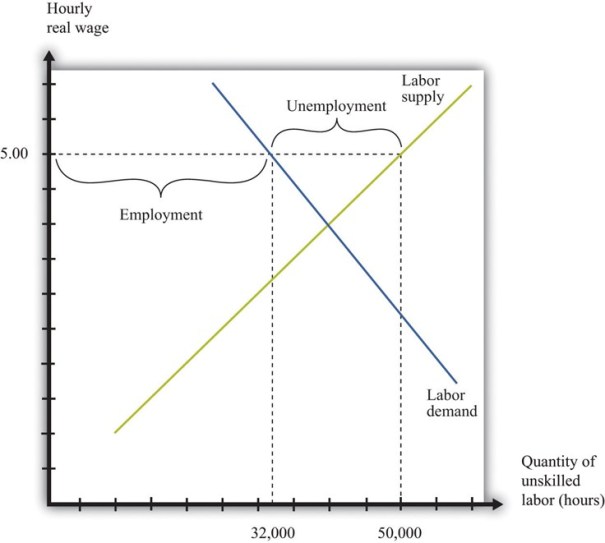

The main potential economic danger of immigration is that immigration of low-skilled workers might possibly contribute to inequality in America by boosting the real living standards of the middle and upper-classes and suppressing the wages of low-skilled Americans. Most research does not support this idea, but George Borjas (an immigrant himself) is one of the few prominent economist who really dislikes immigration.

Why A Wall is Political Theater

Although Borjas hates immigration, he does not believe a border wall does any good. It is easy to see why. Suppose you have a delicious nut tree, but squirrels have been coming from the forest on one side and they are eating the nuts, so you decide to build a fence around the tree, but you only put the fence around 38% of the border and a lot of that fence is only designed to stop vehicles, not walkers. How effective would that fence be? Furthermore, the squirrels have ropes and ladders for climbing over the fence and most of the fence is in a place where nobody is around to monitor it. Hardly any squirrels bother to bring a ladder because there are so many easier ways to get inside like to just walk across along most of the border where there is no barrier. Plus, you invite millions of squirrels each year to enter through gates in the fence to visit the tree on tourist visas. Many of them never leave.

This silly story is just like America’s border wall. Even Donald Trump has stopped talking about the wall. It was central to his 2016 campaign when he promised, hundreds of times, to build a wall across the Mexico border and make Mexico pay for it. In the end he added just 80 miles of new wall (which was just 47 miles of primary wall plus 33 miles of secondary wall built to reinforce the existing primary barrier). It is easy to see how that didn’t make much difference on a border that is nearly 2000 miles long. He spent most of the money improving the existing barrier that previous administrations had already built because that was easier than trying to build a wall on new territory. Despite the record expenditures on the wall it didn’t stop a surge of migrants that began during Trump’s last year in office and reached a record peak during the Biden administration. That was why he stopped talking about the wall.

Deportations are also mostly Political Theater

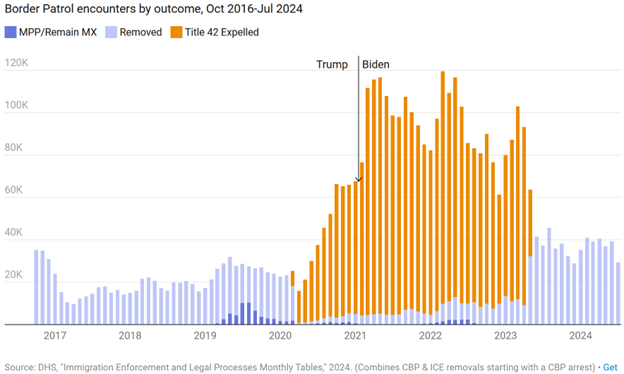

Who arrested more immigrants, Trump or Biden? Most would be surprised to learn that Biden arrested FAR more immigrants than Trump. This graph, by the conservative Cato Institute, shows the total and even includes the refugees who were forced to remain in Mexico while they awaited their asylum hearings which was much bigger under Trump than Biden.

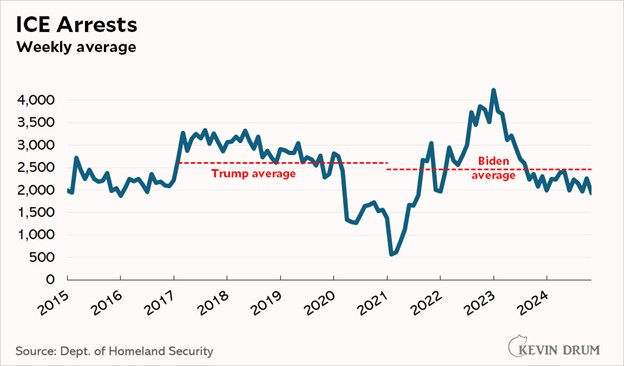

There are basically two places immigrants get arrested, at the border by the Border Patrol and within our communities by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE “raids”). There is very little difference in the number of ICE raids during Trump and Biden:

Deporting people isn’t as easy as you might think. The American Immigration Council estimates that it costs the government an average of $88,000 for each deportation. Most of that cost is for keeping each immigrant in jail while the government negotiates for their release. Jail is VERY expensive accommodation, and it can sometimes take years to get another country to accept a forced repatriation.

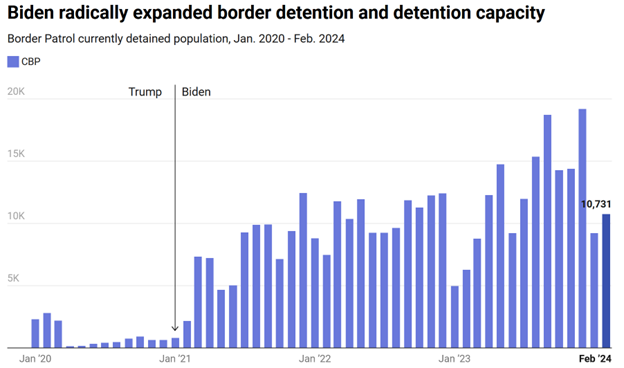

Who jailed more immigrants, Trump or Biden? You guessed it!

Most people THINK that Trump deported a lot more foreigners, but that is mainly because Trump is much more theatrical about immigration than Biden. When we combine the data, Biden actually deported, expelled or detained 73% more immigrants than Trump.

What causes illegal immigration to America?

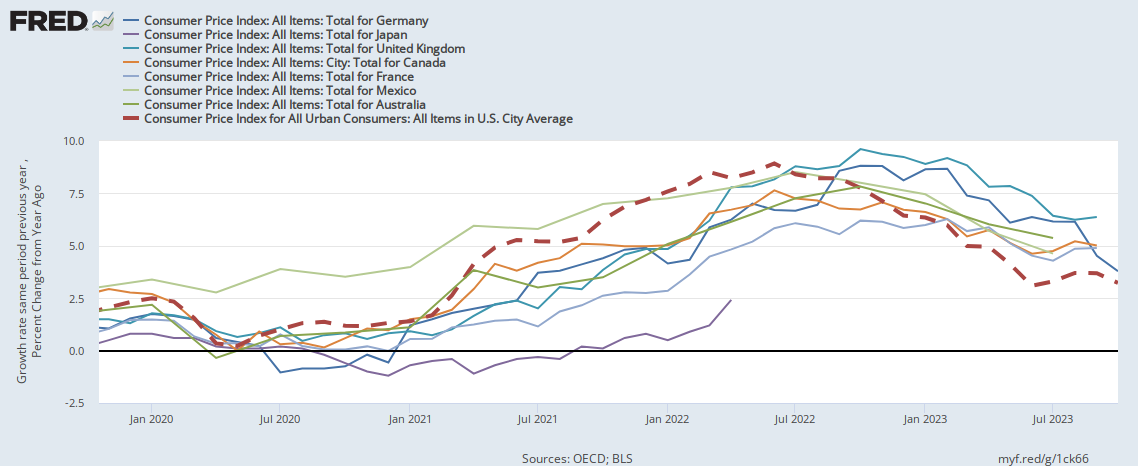

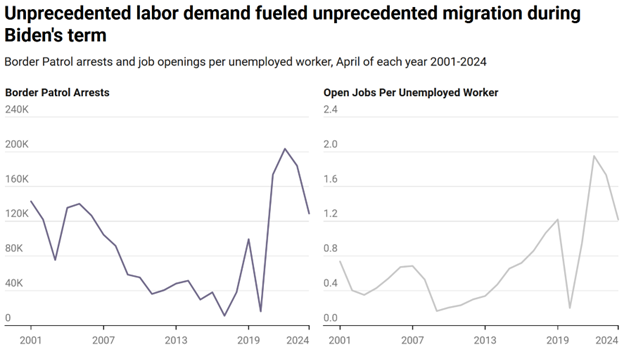

There are three main causes: jobs, jobs and jobs. This is the PULL that brings immigrants. Some analysts also correctly point out that there are PUSH factors like the political repression and economic collapse that has pushed 20% of Venezuelans to leave their country or the Syrian war that displaced half of that country, but push factors only explain why people leave a place and there are always push factors somewhere in the world. Push factors have very little power to explain why those migrants go to America rather than Guatemala and why few people wanted to go to America in 2010 whereas many came in 2021. By far the main driver of immigration to America is jobs.

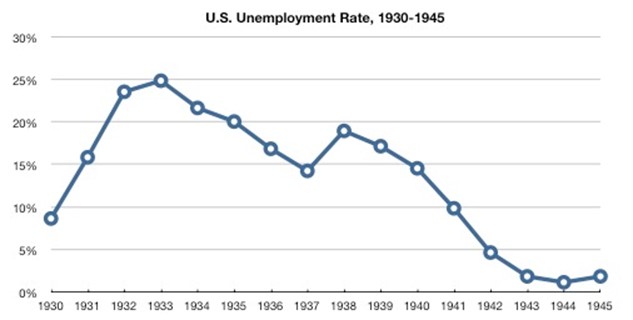

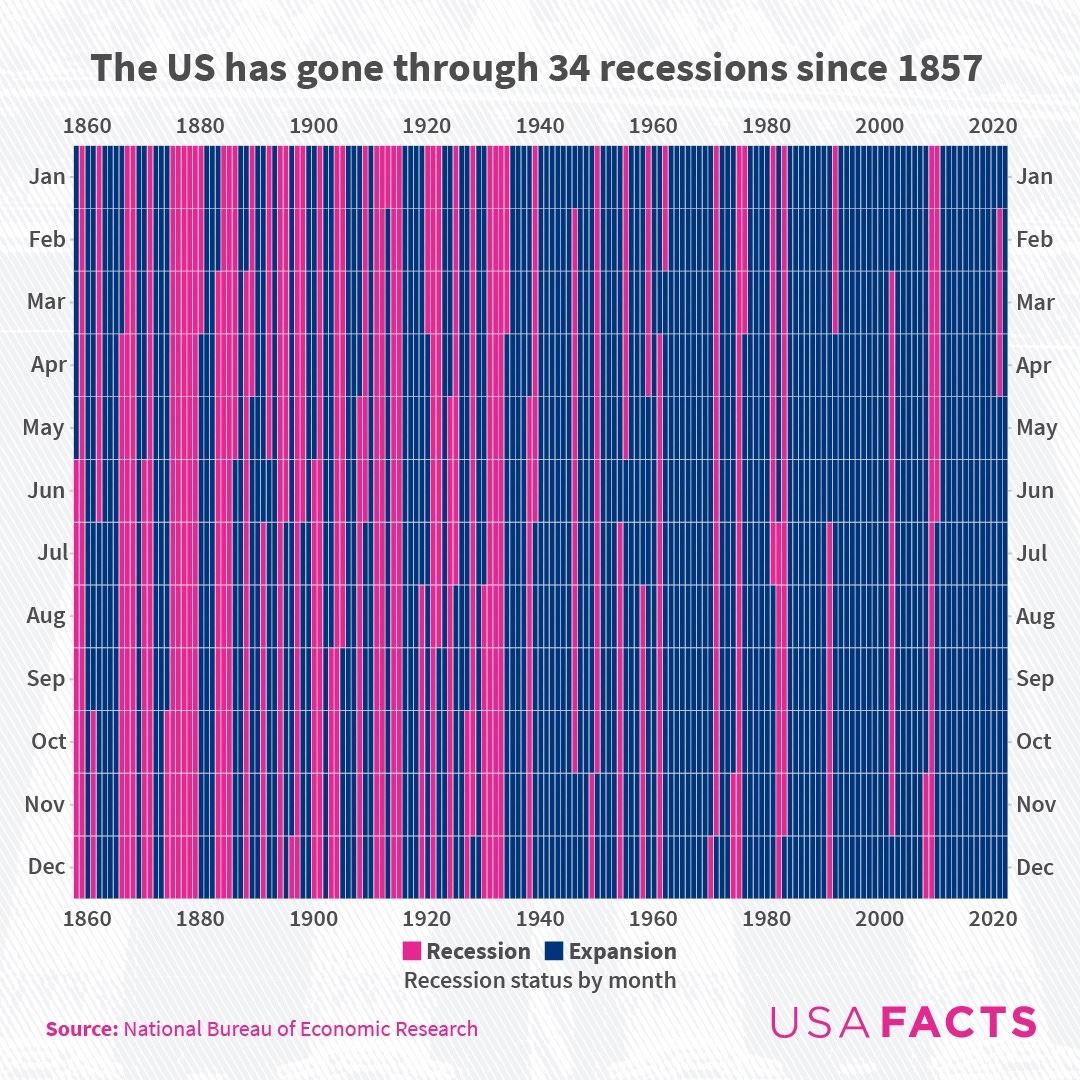

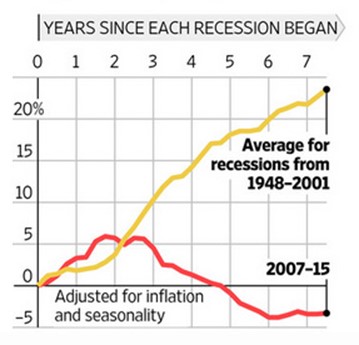

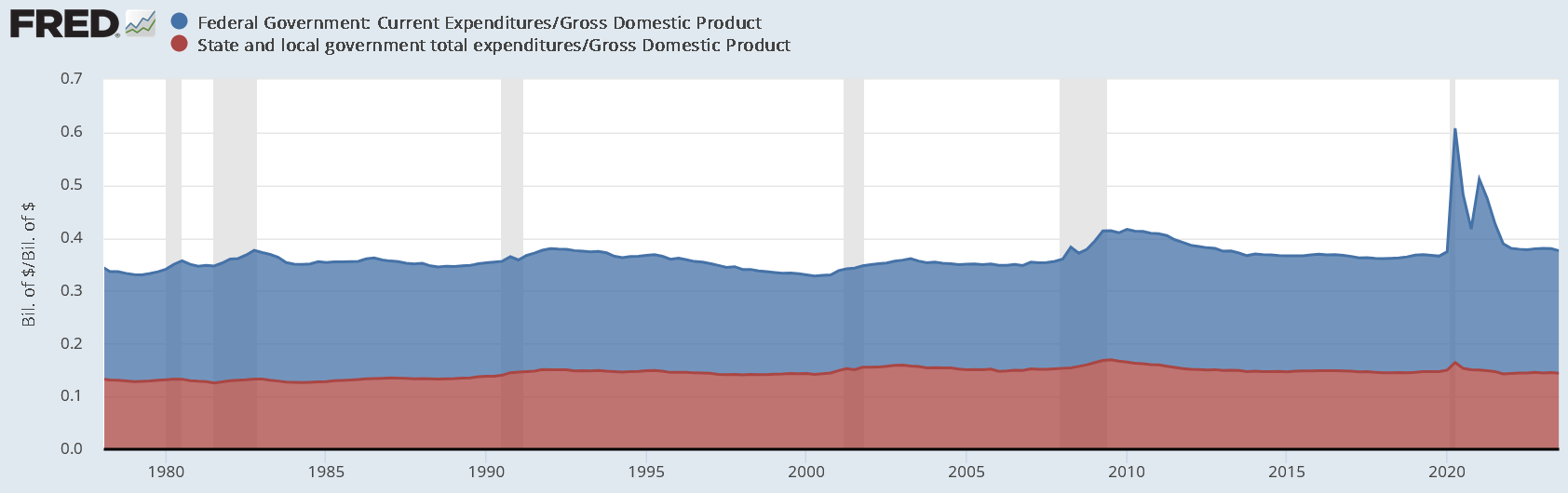

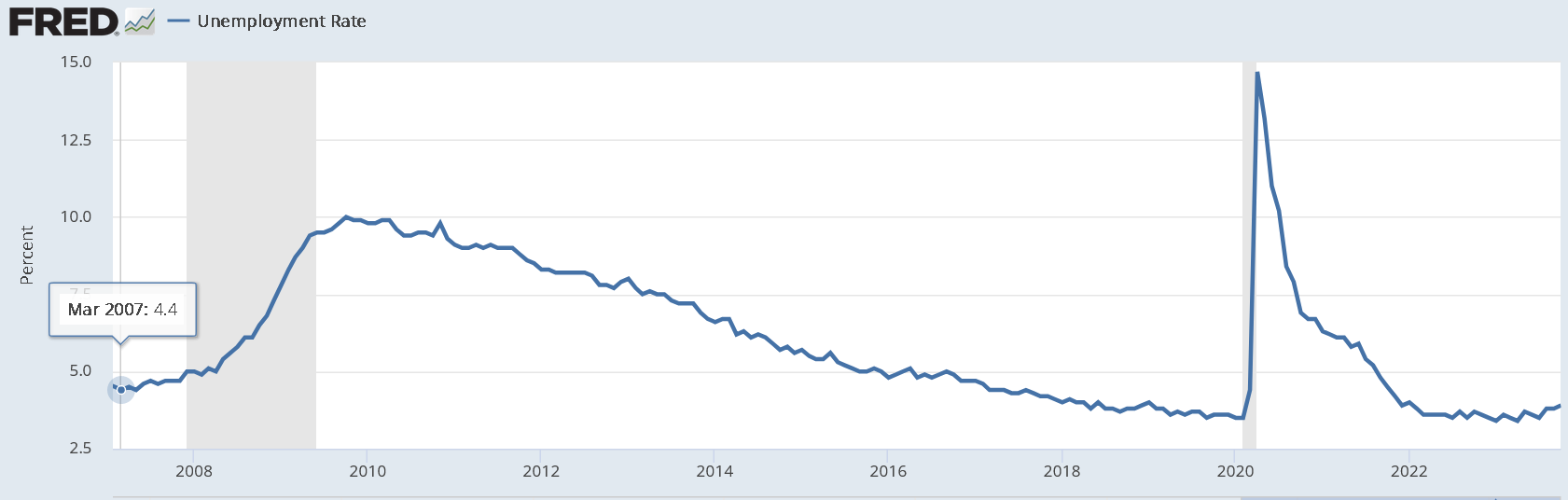

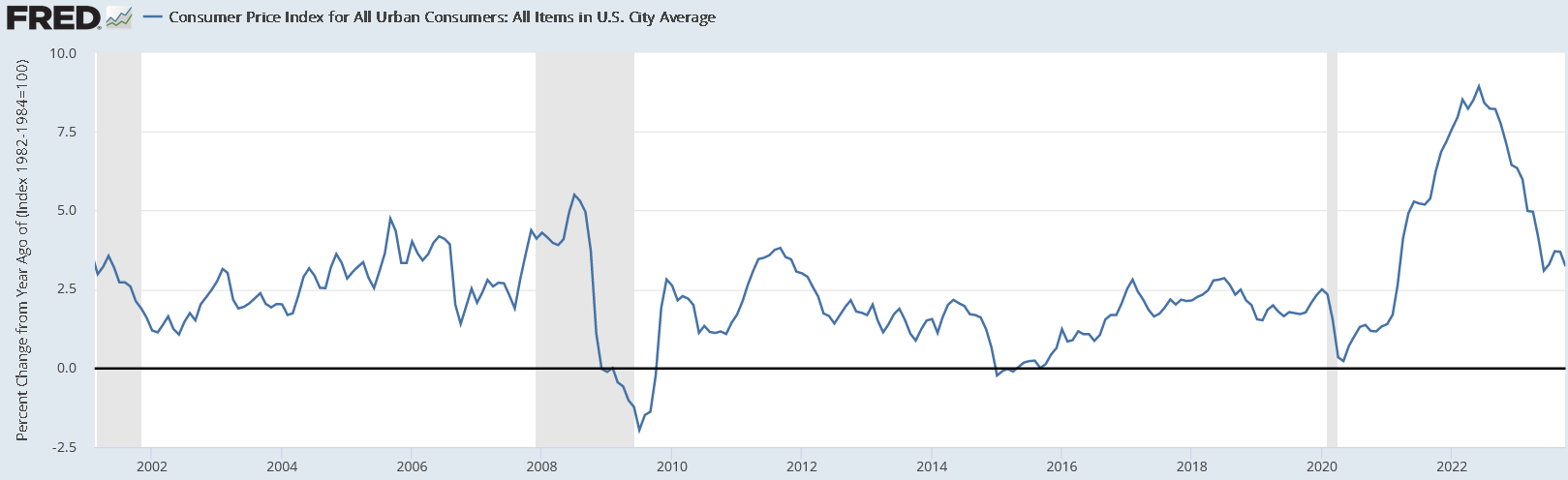

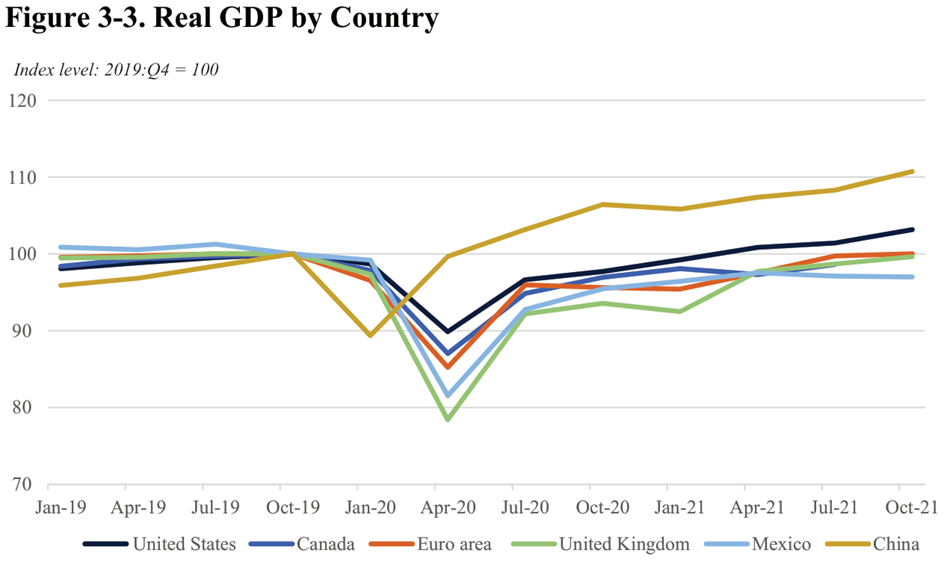

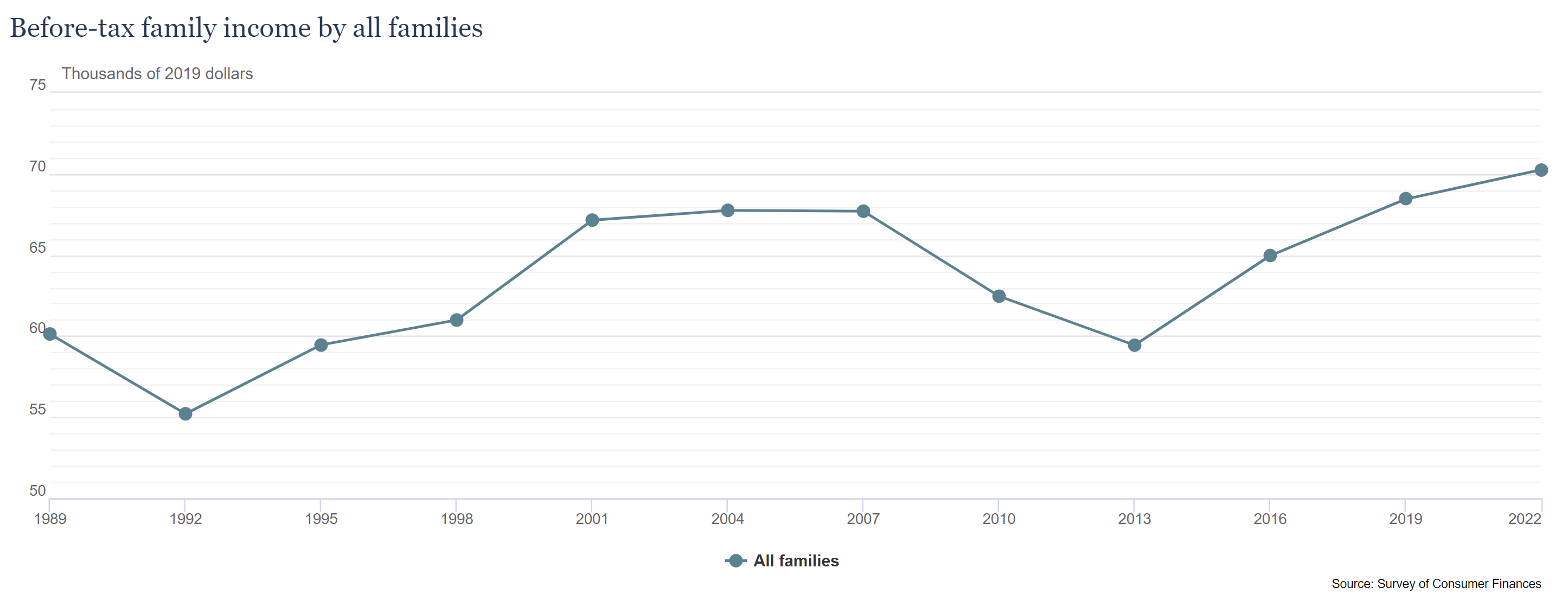

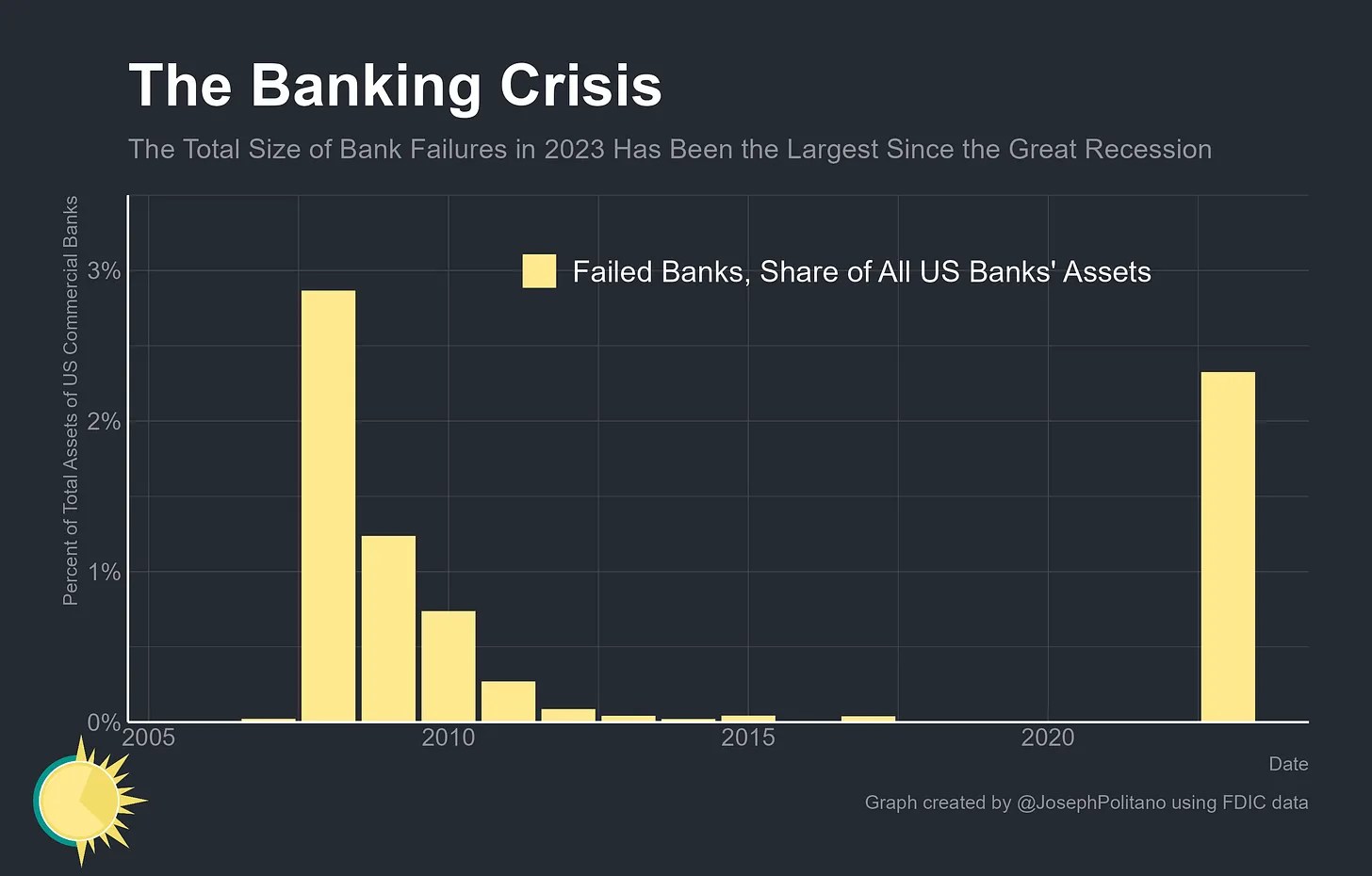

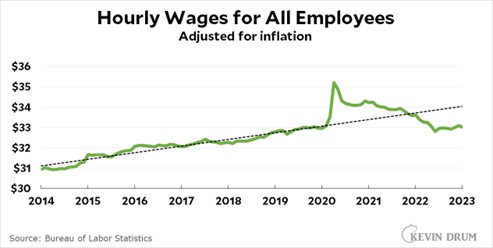

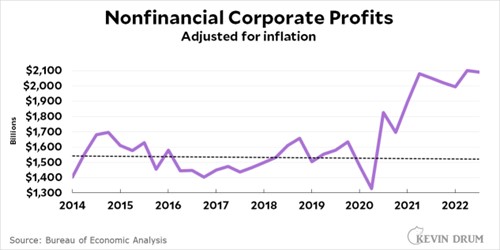

When labor markets are weak, like in 2007-2012, there are fewer immigrants. In fact, about a net of a million illegal immigrants self-deported and left the country during this time. The biggest reason for the migrant boom from 2021-24 was the exceptionally high number of job openings in America.

Why most immigration policy is political theater

The Wall Street Journal recently reported that Ron DeSantis has passed laws that radically crack down on immigration, but despite the fanfare, “the law hasn’t resulted in huge disruptions to the state’s labor market, as some predicted.” This is because, “Certain provisions were watered down before the bill passed or in its implementation, and the state has done little to enforce the law.”

This is typical immigration policy in the US. Like Trump’s wall, it gets a lot of press, but it doesn’t actually do much to change the labor market that is dependent upon undocumented workers. This is the sweet spot for the powerful business owners who dominate our political system. They get to keep most of their undocumented workers AND those workers become more afraid and docile. Businesses love immigration because they like to have more choices for hiring workers and the business lobby is the most powerful economic force in Washington. They are happy to play along with political theater that wastes a lot of tax dollars as long as it just makes immigrant workers more docile. They will block policies that actually cause them significant problems hiring immigrants.

If politicians were serious about immigration, they could eliminate most undocumented immigrants at zero cost to taxpayers!

It costs somewhere around $80,000 to deport each undocumented worker, many of whom make less than $20,000/year, but if we got rid of their jobs, they would be forced to leave. It would be a LOT cheaper to get rid of their jobs than to deport the workers. All we would have to do is fine the employers who hire them. These fines would generate income for the program so it could pay for itself! There would be no expensive jails for undocumented immigrants and the government wouldn’t have to pay for expensive flights. Most would voluntarily leave to look for better opportunities somewhere else.

Imagine if when the police raided a drug den, they just rounded up the addicts and left the drug dealers free to continue their business. That is basically how deportation works. Almost every time ICE raids a workplace and rounds up workers for deportation, it leaves the job dealer Scott-free to hire more undocumented workers again the next day. This is why deportation is political theater that doesn’t work. It doesn’t do anything about the root cause of immigration. If it is illegal for a foreigner to work in American then it should be illegal for an American to hire a foreigner, but in practice, fewer illegal job dealers get prosecuted than Americans who get struck by lightning. For American employers of illegal workers, the risk of dealing with ICE is just a small, manageable cost of doing business.

We already have an effective program for employers to check the immigration status of workers, but it just isn’t enforced. Here is Kevin Drum commenting on a LA Times article:

Don Lee at the LA Times writes all about it:

Even though E-Verify is free for employers, with more than 98% of those checked being confirmed as work-authorized instantly or within 24 hours, the program is significantly underused.

….In its earlier years E-Verify was riddled with errors, but today is seen as highly reliable. Of the 10 million employees checked through E-Verify in the first quarter of this year, fewer than 2% were flagged as mismatches. Of those, about 18,000 employees, or only 0.2% of the total, were later confirmed as work-authorized.

In other words, it’s 98% accurate within 24 hours and 99.8% accurate overall. And it’s easy to use. Despite this, few businesses use it and it’s not mandatory. Why?

Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah), with Republican colleagues including Ohio Sen. JD Vance, former President Trump’s running mate, in June introduced a bill to make E-Verify mandatory across the country. But similar efforts in the past have repeatedly failed to win enough bipartisan support.

….In Washington, many Democrats have indicated they will support a national requirement only if it is part of an overall reform that includes legalization of undocumented immigrants currently in the U.S., which most Republicans oppose.

Republicans also face resistance from some employers and special interest groups, whether farming or construction or other service sector that relies on immigrant labor. For them, it’s a bottom-line issue.

The not-so-secret truth is that nobody really wants to get rid of undocumented workers:

One key reason: There are simply not enough “legal” workers to fill all the jobs a healthy, growing U.S. economy generates. And that’s especially so in low-wage industries.

Employers say that requiring E-Verify — without other overhauls to the immigration system, including easier ways to bring in workers — would be devastating.

“I think you would see a general overall collapse in California agriculture and food prices going through the roof if we didn’t have them do the work,” said Don Cameron, general manager at Terranova Ranch, which produces a variety of crops on 9,000 acres in Fresno County.

….It’s not simply a matter of not having enough workers to do the hard, often dead-end and low-wage jobs that most U.S. citizens don’t want to do. It’s the shortage of workers overall, experts say.

For decades, birth rates in the U.S. have been declining, as they have in most of the economically developed world. Today, the birth rate among American women of childbearing age has dropped below the level needed to meet the country’s replacement rate. California’s birth rate is at its lowest in a century. If the economy is to grow and prosper, as almost all Americans say they want it to, additional workers must come from somewhere else.

Getting rid of immigrants wouldn’t solve any of America’s ECONOMIC problems

There is overwhelming evidence that immigrants don’t reduce job opportunities for native-born Americans. If anything, they help the average American. Of course, even though immigrants help most Americans doesn’t mean that there aren’t a minority of Americans who really wanted to pick strawberries and who end up doing something else instead because immigrants pick the berries for a lower wage.

Immigrants do not cost taxpayers. Overall, like native-born Americans, they pay as much in taxes as they get in government services. Actually, undocumented immigrants tend to be a net positive because they aren’t eligible for most services and they still have to pay taxes. A 2016 report by the National Academy of Sciences found that immigration’s fiscal impact is positive for everyone except the very least-educated immigrants. Again, there are exceptions to the general rule (particularly the least educated!), but if we throw them all out, we’ll not end up any richer.

Immigrants have a lower propensity to commit crimes than native-born Americans. Of course, this statistic is excluding the crime of living in America and working for pay, but that is a victimless crime! For example a 2020 paper found that:

Relative to undocumented immigrants, US-born citizens are over 2 times more likely to be arrested for violent crimes, 2.5 times more likely to be arrested for drug crimes, and over 4 times more likely to be arrested for property crimes.

And the Marshall Project found that places with more undocumented immigrants tend to have slightly less crime.

Although immigration is good for economic statistics, it also affects American culture.

America has the right to control our borders and decide who can immigrate here and who cannot. That is what sovereignty means. Even though immigrants help the US economy, they also affect our culture and it is certainly legitimate to decide to do something costly to preserve cultural values. Oddly, however, it would seem like liberals would have the most to fear from immigrant cultural values because most immigrants come to America with more conservative social values than the median American. They would be natural Republican supporters if Republicans embraced immigrants like they did in the past. In fact, Ronald Reagan was pro-immigration and signed the last big amnesty bill when he was president. California was a Republican state under Reagan and remained so until the Republican Party sponsored an anti-immigrant program which turned Hispanics against the party thereby turning the state blue. Of course, this is changing as most immigrants since 2010 have not been Hispanics. This perhaps helps explain why Hispanics in America are starting to turn against immigration too, just like previous waves of immigrants who do not like the strange cultures of newer immigrants.

American employers are paying them to come

The rise of non-Hispanic immigration also helps explain why illegal immigration from Canada has been surging. Immigrants to the US first try get a tourist visa to the US which is the easiest way to get in. In the past, between 1/3 and 1/2 of America’s unauthorized migrant population entered legally. If that fails, non-Hispanic migrants prefer to try Canada next because it is ridiculously easy to cross from Canada and only if that fails do they resort to first entering Mexico or farther south and traveling overland. The changing origins of American immigrants also explains why more are hiring boats to bring them in.

There are numerous businesses that shuttle unauthorized immigrants across Central America and help them cross the US-Mexico border. Other businesses smuggle migrants in by boat and if America puts up a longer wall, these entrepreneurs will find the weakest parts of the border and continue to smuggle immigrants in as long as American employers are demanding immigrant workers. As long as employers are free to employ unauthorized immigrants, there is just too much money to be made to stop this trade.

As long as American employers are paying them to come, they will find a way to come.