Henry George promoted a revolutionary plan for the tax system that economists generally agree would be more fair and efficient, but 120 years after his death, still (almost) nobody cares about his great idea.

Pigouvian taxes are another idea beloved by economists on both the right and the left that never captures the popular imagination.

Although most people claim to love democracy, few people ever think about the nuts and bolts of what kind of machinery of democracy works best. Nearly all voting experts agree that our voting system is the worst possible. There are many alternatives that are fairer and better (like Range Voting), but most people don’t care.

One of the essential parts of the machinery of capitalism is our laws that make corporations possible, but this framework is rarely examined by the public. Now there is another interesting proposal that will probably go nowhere because wealthy interests will oppose it and voters won’t care because it is too wonkish to appeal to the popular mind.

require any corporation with revenue over $1 billion — only a few thousand companies, but a large share of overall employment and economic activity… to consider the interests of all relevant stakeholders — shareholders, but also customers, employees, and the communities in which the company operates — when making decisions. That could concretely shift the outcome of some shareholder lawsuits but is aimed more broadly at shifting American business culture out of its current shareholders-first framework… Business executives, like everyone else, want to have good reputations and be regarded as good people but, when pressed about topics of social concern, frequently fall back on the idea that their first obligation is to do what’s right for shareholders. A new charter would remove that crutch, and leave executives accountable as human beings for the rights and wrongs of their own decisions.

Under current law, corporate executives are required to do whatever is most profitable for shareholders even if it pollutes then environment, addicts users (a particular problem in the tobacco, alcohol, and painkiller industries), or harms employees. If CEOs do something that is good for society at a cost to profits, they can be sued by shareholders and held personally liable. This new proposal would eliminate that legal threat. This is famously associated with Milton Friedman’s widea that “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase its Profits.”

Additionally, the proposal would 40 percent of the membership of their board of directors to be elected by employees. This is roughly how corporations are run in many other nations like Germany and employees generally don’t let CEOs extract as much money out of corporations as they do in the US. As Yglesias notes, “Consequently, German executives earn only about half as much as their US counterparts, even as major German firms like BMW, Bayer, Siemens, and SAP produce world-class results.” Employees also have insider knowledge of how well the management is working which outside board members lack which can help improve corporate governance.

Yglesias argues that this tweak of American corporate charters could help reduce inequality and boost productivity:

The shareholder value era has pretty clearly brought about an explosion in inequality in the United States. It succeeded, for starters, in greatly increasing the value of shares of stock in the English-speaking countries where Friedman’s doctrine has been most influential.

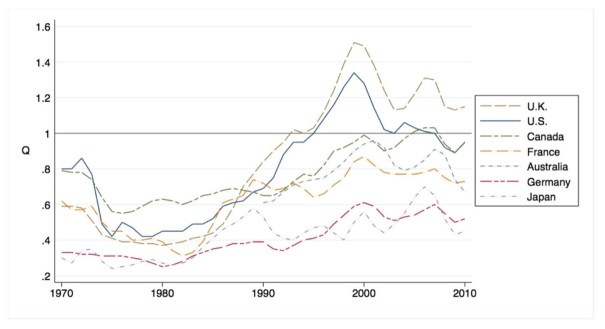

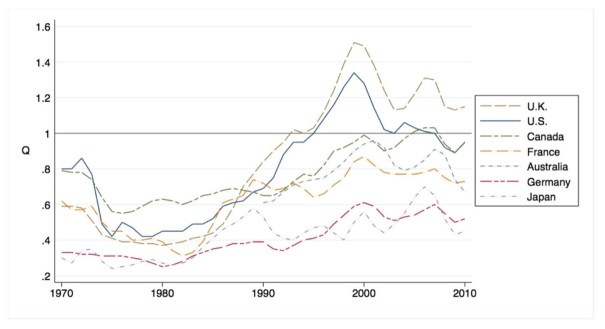

You can see this in the evolution of a ratio known as Tobin’s Q — the value of all the shares of stock outstanding divided by the book value of everything publicly traded companies own.

Historically, this ratio was well below 1, and it remains below 1 in Germany and Japan, where shareholder value does not reign supreme. But in the US, Britain, and Canada, the Q ratio has soared — meaning the financial value of corporate ownership has risen faster than the actual growth of the underlying enterprises — leading to huge increases in wealth for people who own shares of stock.

Thomas Piketty

Thomas Piketty

Since 80 percent of the value of the stock market is owned by about 10 percent of the population and half of Americans own no stock at all, this has been a huge triumph for the rich. Meanwhile, CEO pay has soared as executive compensation has been redesigned to incentivize shareholder gains, and the CEOs have delivered. Gains for shareholders and greater inequality in pay has led to a generation of median compensation lagging far behind economy-wide productivity, with higher pay mostly captured by a relatively small number of people rather than being broadly shared.

Investment, however, has not soared. In fact, it’s stagnated.

And a range of scholars believe shareholder capitalism is to blame. Dong Wook Lee, Hyun-Han Shin, and René Stulz find that firms enjoying high Q now invest in share buybacks rather than reinvesting in business. Heitor Almeida, Vyacheslav Kos, and Mathias Kronlund find that companies strategically time buybacks to manage earnings per share metrics in line with Wall Street expectations and that “EPS-motivated repurchases are associated with reductions in employment and investment, and a decrease in cash holdings.”

Germán Gutiérrez and Thomas Philippon empirically test seven possible causes of decreased business investment, and find that changes in corporate governance (along with reduced competition and a shift to intangible goods becoming more important) is a major factor.

The heterodox economist William Lazonick of the University of Massachusetts puts the thesis very squarely, arguing that “from the end of World War II until the late 1970s, a retain-and-reinvest approach to resource allocation prevailed at major U.S. corporations.” But since the Reagan era, business has followed “a downsize-and-distribute regime of reducing costs and then distributing the freed-up cash to financial interests, particularly shareholders.”

Although these ideas are worth pursuing, they will probably go nowhere because rich shareholders will spend political money to oppose it and wonkish ideas about corporate charters just can’t be captured in a populist slogan, so these ideas won’t be able to overwhelm the concentrated financial interest groups that oppose them.

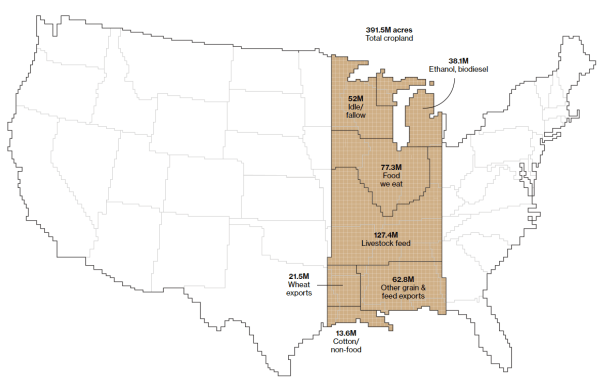

It also shows that the US has more land in military bases than in state parks:

It also shows that the US has more land in military bases than in state parks: