Writing changed the world by allowing one author to communicate with thousands of people. Even though only a few readers could read at the same time, a writing is a memory that can be preserved without corruption for decades and transported over vast distances.

The Population Resource Bureau estimates that nearly 7% of the total population of humans who have ever been born are currently alive today. That is a overestimate because they are assuming that the first two humans emerged only 50,000 years ago. Most scientists think that modern humans appeared at least 200,000 years ago. In any case, the Population Resource Bureau estimates that only 20% of all humans have been born after 1650.

Within that 20%, a small fraction of humans suddenly started becoming much more inventive because Gutenberg invented the printing press in 1436.

In particular, it was the Europeans and their cultural descendants who suddenly became more inventive because Gutenberg was European and his invention was particularly suited to European language and culture. But before Gutenberg came along, Europe had been a backwater for centuries after the collapse of the Roman Empire. If aliens looked at the peoples of the world and tried to predict what civilizations had the most potential at that time at the end of Europe’s dark ages, they would probably pick an Islamic or Chinese nation. The Ottoman Empire had inherited the fruits of the Islamic Golden age and just conquered the last remains of the Eastern Roman Empire. They were about to take over much of the Middle East, Southeastern Europe and North Africa.

The Chinese empire was already massive and they had produced the Grand Canal and the Great Wall and had the best technology in the world. They had just sent a majestic fleet to explore the seas. They sent hundreds of ships with about 27,000 personnel on several exploratory voyages including the largest ships in history dwarfing Columbus’ three ships that sailed at the end of the century. They brought back African elephants, giraffes, and raw materials from all across the South China Sea and Indian Ocean. Below you can compare the relative size of major European and Chinese ships and their voyages.

If the printing press had not come along, the Renaissance probably could not have rapidly spread out of northern Italy to the rest of Europe and it might have fizzled out. Later historians would trace the origins of the Renaissance to the decades preceding Gutenberg, but without the printing press, historians probably would not see the importance of the artistic and political achievements in the tiny Italian city states that were soon copied across Europe. When the printing press was invented, Europe was so backward, nobody would have thought that it would soon come to dominate the world. But Europe suddenly changed after Gutenberg.

Some argue that Gutenberg didn’t really invent the printing press because most of the technologies that he used had been invented by others. His main contribution was merely to combine several existing technologies into a revolutionary new business model that dramatically reduced the price of books. He was the first to figure out how to take advantage of several improvements in metallurgy, moveable type, paper, presses, ink, book binding, scripts, and literacy to produce an entirely new kind of publishing industry. Other than his cleverness (and luck) in combining those technologies into a new package, his main technological innovations were small: he invented an improved formula for ink that stuck to metal type better, and he probably reinvented an improved matrix for casting better moveable type. Gutenberg had been a goldsmith, so he had a perfect skill set for casting better moveable type.

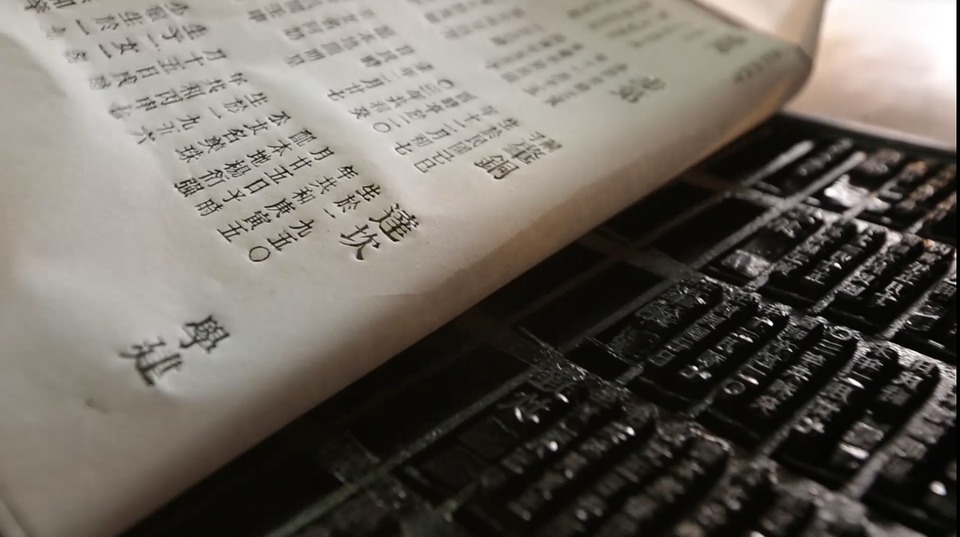

Moveable type is the practice of casting each letter of the alphabet in a separate piece of metal. Each metal letter is arranged in a frame to produce words and sentences. That way the same bunch of letters can be quickly and cheaply rearranged to print any combination of words for every possible page. Previously printers had laboriously carved each unique page in its entirety on a block of wood or other material. It could take days to just get a single page of text ready for printing. With moveable type, the pre-cast letters could be quickly rearranged to produce a new page of text in under an hour.

Gutenberg’s innovation dramatically increased the output of books and decreased their cost.

By Tentotwo Data from: Buringh, Eltjo; van Zanden, Jan Luiten: “Charting the “Rise of the West”: Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A Long-Term Perspective from the Sixth through Eighteenth Centuries”, The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 69, No. 2 (2009), (417, table 2), CC BY-SA 3.0

For example, by 1424, (after being open for 215 years) Cambridge University library still only owned 122 books total and each book had a average value equal to an average farm or vineyard. In market value, their library owned as much as 122 farms worth of books. All those riches could all easily fit on a single bookshelf in my office with the kind of printing that we have today.

Today’s books hold much more information because the paper was so coarse and primitive everyone preferred to books printed on leather instead of paper! Plus, before the printing press, handwritten books needed much more space to create legible words, so only about half as many words could fit on a page.

The Bible was originally divided into 72 separate books because it would have been too heavy and expensive to try to combine them into a single volume. That is why we still call them the books of the Bible rather than the chapters of the Bible. A single Bible was originally a library. A Bible was a collection of 72 separate books because books were so rare and expensive before Gutenberg that many early churches could not afford all of the holy books and different churches had different books. It took three and a half centuries after Jesus died for the Catholic church to first establish what books should be in the official cannon during the Council of Rome and that was the beginning of the official Bible. It took a long time to bring every congregation in line so that they had all 72 books of the Bible and stopped using the extras and most eastern churches maintained a separate tradition with somewhat different books.

Although there were dramatic improvements in paper and printing during Gutenberg’s lifetime, a complete Gutenberg Bible still weighted about 30 pounds if printed on paper and nearly 50 pounds printed on parchment (sheepskin) or vellum (calf skin), so it was still nearly impossible to handle all that information in a single book. The printing press soon enabled each worker to print 30 times more books.

The increased productivity in printing spurred inventions in paper production and book binding which caused further drops in the price of books and by 1500, there were 15,000 books in print that a wealthy library like Cambridge could buy.

Note that this graph estimates productivity growth beginning well AFTER Gutenberg’s invention and does not show how Gutenberg’s initial invention created an immediate revolution in efficiency in the first half century. These graphs just show how much gradual improvement in printing happened well after he died.

The printing industry was the first modern manufacturing industry because it was the first capital-intensive form of mass production using interchangeable parts (movable type) and the first example of manufacturing’s ability to dramatically increase production and reduce costs. Nevertheless, it is not associate with the industrial revolution because it didn’t have any measurable effect on the median standard of living. Most people were still too poor to own any books even at the dramatically reduced cost. And at least 90% were illiterate even some people who had money didn’t have any use for books. Books have always been an insignificant fraction of one percent of GDP both before Gutenburg and after.

Economists typically say that economic growth didn’t benefit ordinary people until it reduced the prices of things that most people spent most of their budget on like clothing, food, and fuel. They usually look at the “hockey stick” graph of world history and note that it looks like the exponential growth kink begins around 1800 (or even not until 1870 according to Brad Delong!). But the industrial revolution really began in England and if we focus on when growth took off in England, it looks like it began not long after the printing press was invented. It is just that a constant exponential growth rate of 1.8% doesn’t look like anything on a linear-scale graph until somewhere around 1800, but economic growth really started far earlier, in the mid 1600s according to the Bank of England’s data, which is shortly after literacy took off.

Jared Diamond’s book, Guns, Germs, & Steel, persuasively explains why somewhere in Eurasia conquered the world, but he didn’t do much to explain why Europe conquered Asian civilizations. One explanation is the printing press. That could explain why Europe subjugated China and not vice versa.

The printing press required an alphabet to work efficiently. Printing didn’t take off in China until the early 1900s, almost 500 years after it began revolutionizing European society! The complex Chinese scripts were just too cumbersome for moveable type, but when offset lithography and other techniques finally began replacing moveable type in the mid 1800s those new technologies made printing Chinese much easier and that helps account for why printing did not take off in China until the 20th century. A history of printing in Japan said the revolutionary invention of lithography was as dramatic as Gutenberg’s invention. The first modern moveable-type printing began in Japan in 1849 when a Stanhope press was given to the Shogun and lithographic printing began shortly after that in 1868.

The complex Chinese script is much easier to manage with lithographic printing than moveable type, but even with lithography, typesetting is slower and more difficult in Chinese than for languages that use alphabets. It is probably no coincidence that China did not take off economically until computers became powerful enough in the 1980s to allow printing in Chinese to finally become as cheap AND as easy to produce as in languages that use an alphabet.

The difficulties of Chinese writing also delayed their adoption of telegrams, typewriters, Braille, linotype printing presses, punch-card computer memory, and computer programming itself. Despite a century of development, Chinese typewriters never achieved the kind of importance they achieved in Western society:

The Chinese typewriter was a metaphor for absurdity, complexity and backwardness in Western popular culture. One such example is MC Hammer‘s dance move named after the Chinese typewriter in the music video for “U Can’t Touch This“. The move, with its fast paced and large gestures, supposedly resembles a person working on a huge, complex typewriter.

Whereas the typewriter for the half of the planet that uses an alphabet look approximately identical, here is a photo of a state-of-the art 1970’s Chinese typewriter. It works completely differently and it is MUCH harder. No mechanical Chinese typewriter ever had a keyboard and although they could never print the vast majority of Chinese characters! They only worked for the most common characters.

It wasn’t until the mid 1980s when the Chinese finally agreed upon a standard way to type with a keyboard (wubi). They could finally use computers with Chinese writing. Until that time, computers in China had to be run using foreign languages that used alphabets. The Chinese government saw this as such a crisis that they considered altogether abandoning their traditional Chinese logogram writing system. Today the most common method of typing in Chinese is to sound out the words using a Roman alphabet with the pinyin system.

Most people think that Gutenberg invented moveable type, but he was far from the first. Jared Diamond points out that moveable type was reinvented several times in history such as in 1700 B.C. in Crete (the Phaistos disk), and again in China and Korea a half millennium before Gutenberg. In fact, Asian societies still use stamps called “name chops” to sign documents that look just like moveable type as shown here at a modern store that sells them:

So one would think that they would have thought to use something just like these chops for printing too, but it never took off except in Korea where printing was strictly limited by the government. That combined with the fact that the population of Korean speakers was small so the total number of printed books in Korean didn’t have much influence. In contrast, most books in Europe were printed in Latin in the first half century after Gutenberg, so there was a much larger market that could buy the books and a larger population of authors who could write in Latin for the European audience.

Earlier inventors lacked the other technologies that made printing finally a commercial success when Gutenberg reinvented it yet once again. Although moveable type had been invented numerous times in history, it didn’t revolutionize those societies because they didn’t have other supporting technologies.

Gutenberg’s development of typecasting from metal dies, to overcome the potentially fatal problem of nonuniform type size, depended on many metallurgical developments: steel for letter punches, brass or bronze alloys (later replaced by steel) for dies, lead for molds, and a tin-zinc-lead alloy for type. Gutenberg’s press was derived from screw presses in use for making wine and olive oil, while his ink was an oil-based improvement on existing inks. The alphabetic scripts that medieval Europe inherited from three millennia of alphabet development lent themselves to printing with movable type, because only a few dozen letter forms had to be cast, as opposed to the thousands of signs required for Chinese writing. (Diamond, 1999, p259)

Not only did printing not revolutionize China when the Chinese invented it in the 1100s, it still didn’t revolutionize Chinese society even centuries after Gutenberg’s innovations revolutionized the Western societies simply because they use an alphabetic script which works much better with moveable type than the Chinese writing system.

The basic Latin alphabet only requires 26 characters to write everything (plus approximately 70 rarely-used characters for capital letters, punctuation marks, and common symbols like the dollar sign) and early moveable typefaces could be organized in a box divided into only ten columns and ten rows.

In the Chinese writing system, they would have needed more than 30 times more little boxes to store the minimal set of 3,000 characters and potentially up to 50,000 boxes to have a more comprehensive set. That would make moveable type maybe 100 times more expensive to use in Chinese than in languages like English.

So it is remarkable that the Chinese accomplished it at all as shown in this photo of wooden moveable type:

But given the cheap labor in China and greater difficulty of using moveable type with numerous Chinese characters, they preferred to use wooden block printing in which each page was custom carved by hand on a slab of wood and then laboriously pressed by hand (rather than pressed by a machine as with Gutenberg’s technology). Woodblock printing is an inferior technology because wooden blocks are much more expensive to carve and produce less sharp images and the blocks wear out much faster than Gutenberg’s metal movable type.

Japan may be an exception that proves the rule. Advanced printing presses took off in Japan much earlier than in China and that may be partly due to their adoption of alphabetic systems for writing. For example, Japanese printing first started with a Romanized script that the Jesuits developed in 1590. The Jesuit system never became popular, but the Japanese also developed their own kind of phonetic ‘alphabets’ representing syllables called kana made up of hiragana and katakana which each have just 46 basic characters and are easily adapted to moveable type. That may have helped Japan develop an earlier printing industry than China developed. Japan also developed early systems of copyright and circulating libraries. And whereas one system of Japanese writing does use Chinese characters (kanji), they use a much smaller set of characters than Chinese. Secondary school students are only expected to know 2136 kanji.

The printing press caused phonetic writing systems to spread and they took over the entire planet except places that had already developed a strong tradition of using Chinese logograms. Phonetic alphabets and syllabaries had a huge advantage over Chinese logograms for printing using moveable type since languages have much fewer sounds than words. Some of China’s cultural offshoots also adopted Chinese writing, notably Japan and Korea, but both of them also later developed phonetic writing systems and that may have helped them develop economically earlier than China.

Although Korea was another early innovator of movable type, it has an interesting history that explains why Korean society was not immediately revolutionized by printing like European cultures were. The primary theory is that printing was monopolized by the central government in Korea which may have recognized the potential threat of the printing press and wanted to control it. The fears of the Korean rulers were prescient because in Europe the printing press led to to religious revolutions and political uprisings. In Europe, neither the church authorities nor governments realized the extent to which the printing press would soon cause revolutions that would overthrow their power. Jeremiah Dittmar wrote that, “regulatory barriers did not limit diffusion [in Europe] because printing fell outside existing guild regulations and was not resisted by scribes, princes, or the Church (Neddermeyer 1997, Barbier 2006, Brady 2009).”

The Islamic world was a center of learning partly because Muslims call it a religion of the book to emphasize the sacredness of the written text. The word “quran” simply means ‘reading’ and the quran:

“transformed Arab society into a pre-eminently literary culture …[where] textuality became the predominante characteristic …and came to permeate Muslim society… The writing and copying of texts was an essential and integral part of this endeavour; during the 8th-15th centuries in Muslim lands it reached a level unprecidented in the history of book production anywhere.”

But moveable type was very slow to revolutionize Muslim society. Italy was the home of Arabic printing beginning with the first book printed on behalf of Pope Julius II for Arab Christians and continuing through the 16th century. Even in through the 19th century, printed Arabic books continued to flow from Europe to the Arab world and the first Arabic book printed in the 18th century. There were several reasons why the Arab world took many centuries to embrace the printing press.

- A full Arabic fount can contain over 600 sorts due to the abundance of letter forms, ligatures, and diacritics. That is much more expensive than the 52 letters in both upper and lower case.

- Arabic script is cursive which is harder to carve and more delicate to reproduce in printing. That is one reason it required many times more typesets than Latin alphabets.

- Book printing was challenged by the entrenched monopoly of the scholarly class called the ulama who had intellectual authority. Islamic governments also wanted to control information and even after modernizing rulers finally sponsored a few of their own printing presses, they did not give freedom of the press to private individuals.

- The foreign technology of mechanical reproduction was seen as sacrilege by many Muslims, particularly printing for religious texts which was the most common use of early printing in both Europe and the Islamic world. There were rumors that the ink used pig hair which is seen as a profane animal. Presses could not match the highly-refined style of proper Arabic calligraphy whereas printed text in the Latin alphabet usually looks more precise than handwriting.

- Joseph Henrich argues that Islamic culture was less interested in the kind of individualism and liberal ideas that flourished with printing. He points out that there was a second technology that revolutionized European society at the same time as the printing press: the mechanical clock. Every European town spent a large amount of resources to buy and maintain large clocks and even among the poor, a large percentage of workers (about 40% in England) bought pocket watches. Islamic culture simply had much less interest in non-religious texts and time keeping for parallel cultural reasons.

Most of the early printing in Arabic was done by Christian minorities or European missionaries that did not have these religious and aesthetic constraints, but they did not reach a large audience. Indigenous Muslim printing did not take off in Arabic until the advent of lithography in the mid 1800s which could finally reproduce the stylistic calligraphy that they considered (and still consider) sacred. Lithography had only been used in Europe for reproducing pictures and maps because it was much more expensive than moveable type, but it finally brought widespread mass-produced books to Muslim cultures. By the turn of the 20th century, printed books finally displaced expensive handwritten and block-printed books although it took a bit longer for printed Qurans to become the norm.

The greatest empire of the Muslim world during the age of printing was the Ottoman empire where printing in Arabic script was punishable by death for centuries although printing in other scripts like Greek or Hebrew was allowed. Printing in Arabic was legalized in 1727, but Ottoman printing did not take off until the mid 19th century:

…the major Ottoman printing houses published a combined total of only 142 books in more than a century of printing between 1727 and 1838. When taken in conjunction with the fact that only a miniscule number of copies of each book were printed, this statistic demonstrates that the introduction of the printing press did not transform Ottoman cultural life until the emergence of vibrant print media in the middle of the nineteenth century”

In contrast, about 12.6 million books were printed in Europe (and 27,704 different titles) between Gutenberg’s invention of the printing in 1454 and 1500, only 46 years later. Literacy and printing in Turkish were further boosted in 1929 when Atatürk replaced Arabic letters with the Latin alphabet for writing Turkish. He was partly motivated to simplify Turkish writing and boost literacy as well as by the needs of the telegraph and to facilitate more use of the printing press (Zurcher, 2005, p.188).

Nick Szabo wrote an excellent essay about how printing changed European culture entitled Book Consciousness, but he has unfortunately taken it down, so I’ll repost sections here:

Marshall McLuhan, Elizabeth Eisenstein and others have described the importance of the “printing revolution” to European developments such the Reformation, Renaissance, and science. According to Eisenstein, printing finally foiled the entropy that had destroyed the vast majority of written works since ancient times. Printing also enlarged the bookshelves of scholars all over Europe: by a factor of fifty or more by the middle of the 16th century.

I’d go even farther than Eisenstein. Printing soon brought literacy to vast numbers of people (eventually to the vast majority of us). Printing, especially printing in newly standardized vernaculars, changed the very consciousness of people, and turned a small corner of the world, Western Europe, into a culture that in conquered the world. Widespread decentralized printing and the accompanying book markets, new schools, and rise of literacy gave rise to a new form of consciousness — book consciousness.

Columbus was among the first generation of navigators who had been reading avidly and widely since a child. On his bookshelf was Marco Polo’s Travels. On his voyages he carried maps made by geographers who had been literate since they were children, and he carried astronomical tables that had been printed widely across Europe. These tables had been made by a Hungarian-Italian mathematician whose bookshelf was full of ancient Greek science and mathematics. Such information had been rather inferior and far less available just a few decades before.

With the easy conquest by tiny Portugal of Asia’s vast and ancient sea trade routes, rapidly literizing Western Europeans were by the early 16th century demonstrating a vast superiority in naval affairs. In navigation as in battle officers using accurate charts and astronomical tables were at a premium. (Europeans did not have quite such good luck on land against the Turks). Western Europeans would retain completely uncontested (except among each other) naval superiority on the world’s oceans until the Japanese victory over Russia in the early 20th century. The Japanese by then had long since taken up printing and had a very well read population . Even on the ground by the 18th century English merchants, officers, and civil servants, practically all of them literate and widely read since young children, were finding it quite easy to conquer and take over the administration in far larger and otherwise highly advanced civilizations like India.

Soon after the spread of the printing press, the very fundamentals of organization in Western Europe began to change. In the late Middle Ages organizations, even royal and papal bureaucracies and banking “super-companies”, rarely engaged more than a few dozen employees. Organizational size came up against the severe limit of the Dunbar number. By the end of the 16th century, the colonial companies and bureaucracies of Spain and Portugal were vast, highly literate, and well coordinated. Officer corps had often been raised on military books and thus able to draw lessons from a wide variety of ancient and recent battles. Even a minor salt extractor in Wear, England, was employing 300 men by the mid 16th century. (Large organizations in manufacturing would largely have to wait until the 18th century and the industrial revolution, however).

Before book consciousness there had been no national languages, but only a range of often mutually incomprehensible dialects and in Western Europe the language of the tiny literate elite, Latin. With newly unified national vernaculars, organizations were able to coordinate and grow in an unprecedented manner. A much larger group of people, raised on the same written language, increasingly also came to look and speak similarly and become far more mutually trusted. It was the birth of national loyalty and nationwide webs of trust. The “tribe” to which we are instinctively loyal vastly increased in size. The pool of already somewhat trusted “same tribe” people from which a bureaucracy could recruit new members vastly increased. National polities and militaries were able to coordinate political, economic, and battlefield strategies in an unprecedented manner. The 16th century saw the first major growth of the joint-stock corporation, enabling far more capital to be invested in the enlarging organizations that engaged in mining and manufacture as well as government and conquest. This development is probably a response to the new ability to form larger organizations, since the basic ideas (corporate law, shares of stock, etc.) had already been in use in Europe for quite some time. Some of the early English 16th century joint-stock companies included military expeditions (Drake’s privateering voyages and naval actions were financed through joint stock companies: a different company for each expedition), trading and slaving companies (the Muscovy and Guinea companies) and mining and manufacturing companies (the Royal Mining Company and the Royal Batteries & Mines Company). The most famous became the English East India Company, but many of the American colonies were also joint-stock corporations. The first widely traded and initially most successful joint-stock company was the Dutch East India company, which quickly grew far beyond the Dunbar number to have thousands of employees.

Book consciousness changed almost every profession. Good books on a trade could greatly increase the knowledge imparted during apprenticeships, and indeed eventually led to the end of the apprenticeship system. Meanwhile, widely printed books on mathematics and science, such as Euclid’s Geometry, gave knowledge that could be used in a wide variety of occupations, and training was often restructured to assume and build upon such new general knowledge. This led to a profound change in labor productivity, moving mankind away from the Malthusian curve and (along with the expansion of organizational size beyond the Dunbar limit) eventually to the industrial revolution.

A typical example of the rise of book consciousness was the radical improvement in how cases were reported in the English legal system by the late 16th century. For the first time, cases and statutes were widely and accurately cited. This reflected the fact that judges, barristers, attorneys, and even some of the parties had for the first time printed books of statutes and cases at their fingertips — instead of having to find the single copy of a scroll hidden away in some monk’s or bureaucrat’s library. The first great English opinion writer, Sir Edward Coke, dates from this period. In turn, the wide availability of printed statute and case law led to basic changes in the way we interpret and view the law.

Almost invariably, during the colonial period, when largely illiterate cultures (i.e. cultures where most of the second-tier nobility, military officers, and merchants, and almost all craftsmen and farmers, had not been raised on books) were encountered by literate Europeans, the latter described the former with severe epithets, such as “savages.” This makes our forbears seem odious to us, who understand that all human races are capable of literacy, and indeed by now book consciousness has spread to most of the globe and most of us encounter a wide variety of highly literate people every day. However, at least in the 16th century for book-raised Western Europeans this was not so much a racial prejudice as a largely accurate observation. “Savage” was applied not only to Neolithic Africans and Americans, but also to Irish backlanders and Scottish highlanders. There was a similar Western European attitude to otherwise very advanced civilizations in India and China. From the 16th century onward, any culture that did not have book consciousness was a culture of savages.

It’s possible that today the availability of thousands of times still more material to read, readily accessible by search engine, and the expansion of a small number language groups (but especially English) to a worldwide real-time network is creating a new “Internet consciousness.” People within this network may soon come to see people outside of it as savages.

…If I had to pin down three key differences between East Asia and European reception of printing they’d be (1) a small phonetic alphabet is more suited to printing and was already standard and widely used in Europe, (2) the decentralized nature of European printing business (Europe within a couple decades of Gutenberg had many competing printers not directly controlled by a government or religious organization), and (3) the widespread nature of European learning — especially the universities and the already literate merchants. The need for universities in turn was driven by the almost uniquely European need for those much-maligned lawyers. There’s a strong relationship here to the European adversarial legal system (as opposed to bureaucratic legal systems dominant in Asia).

The Chinese language has about 50,000 characters rather than the 26 used in the European alphabets, so even though the Chinese invented printing, it never became widely used because it was so expensive to do, and it was more of an art form than a means of mass media. Lots of civilizations had been printing with custom-carved wooden blocks, but Gutenberg’s great innovation was metal moveable type which finally made printing cheap and easy to do. The Chinese got European-style moveable type in the 1700s but it required about 250,000 types to be cut by hand from bronze to print books and the expense of using moveable type constrained printing relative. Relatively expensive xylography (wood-block printing) dominated Chinese printing until the late 1800s when techniques like lithography finally replaced it.

The lack of an alphabet also constrained the next great leap in communications technology, the telegraph, which reshaped business in the West beginning in the mid 19th century. Although the telephone replaced the telegram for local communication, the telegram continued to be preferred for long-distance communication for decades and the peak in telegraph messages happened in either the 1920s or perhaps as late as the 1940s. The telegraph revolutionized corporate America by permitting the rise of huge centrally-controlled conglomerates. It was particularly revolutionary in coordinating military operations, railroads, financial markets, and news organizations:

the railroads needed the telegraph to coordinate the arrival and departure of trains… The greatest savings of the telegraph were from the continued use of single-tracked railroad lines… The potential for accidents required that railroad managers be very careful in dispatching trains… By using the telegraph, station managers knew exactly what trains were on the tracks under their supervision…

Telegraph and Financial Markets

…in 1846, wheat and corn prices in Buffalo on the west end of the Erie Canal lagged four days behind those in New York City at the other end. In 1848, the two markets were linked telegraphically and prices synchronized immediately. The telegraph allowed centralization of stock prices and helped make New York the financial capital of the United States. Over the course of the nineteenth century, hundreds of stock exchanges appeared across the country as the economy grew and then as telecommunication created economies of scale, they disappeared again. Few of them remained, with only financial markets in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago and San Francisco achieving any permanence. By 1910, 90% of all bond sales and two-thirds of all stock trades occurred on the New York Stock Exchange.

The telegraph was adopted more rapidly in China than book printing even though it was also harder to use in Chinese because each character was assigned a number which had to be transmitted using Morse Code and then looked up in a large code book. Each code book only needed about 3,000 of the most common characters which would fit into a very slim book and every telegraph office in China only needed one book per telegraph, so the writing system wasn’t much problem at all. even though it was nearly impossible for anyone to memorize all the codes, Morse code was very efficient at communicating Chinese with very few keystrokes when using a code book.

Nick argues that the rise of large private companies was impossible without mass literacy and easy written communication. In particular, the corporation was impossible because it was a form of mass democracy which relied upon cheap printed communication to coordinate shareholders, but large private companies of any form had been impractical before Gutenberg. Although there had been a few relatively short-lived large ‘supercompanies’ in the city states of northern Italy such as the Compagnia dei Bardi, they were unusual as Nick says:

The Bardi supercompany was quite exceptional and didn’t last very long. You’d have a very hard time finding any other examples in the entire stretch of civilization from the Sumerians in 3,000 BC until the European 16th century where Dunbar number (really a range between about 100 and 200 people where organization becomes quite difficult) was exceeded for any long period of time by a commercial organization. The Dutch East India Company, with its managers and most of its employees raised on the same common language due to printing, was the first company to do so, and quite exceptionally so (it had by the 17th century over 10,000 employees if I recall correctly) and many other companies (mostly English) soon followed within a century.

This radical change in the ability of businesses to organize employees the leads directly to European empires, and later to the industrial revolution. It cries out to be explained. It corresponds to the rise of literacy in a common language. The most likely cause is the expansion of the perceived “ethnic boundary” created by language …or the “tribal illusion” and resulting network of easily trusted people… This phenomenon explains the exceptional (but comparatively very humble) pre-printing-press example of the Florentine supercompanies as well. But had it not been for the printing press that Renaissance, like many earlier ones, would have died and been largely forgotten.

The Dunbar number is important in all this because it’s a psychological limit on how many people we can get to know well enough to develop the long-term relationships needed for solid trust. …Christopher Allen… has observed that corporate culture changes radically as the size of organizations grow larger and in particular as they exceed the Dunbar range…

Before the European printing press commercial organizations almost never exceed the Dunbar number. …[T]he early 14th century “supercompanies”…[like the the Compagnia dei Bardi], only barely and temporarily exceed the Dunbar range. This was probably made possible by the unusually high level of literacy in a common language …among the Florentines.

Large organizations were only possible when people’s activities were coordinated by religious belief (church organizations) or threat of force (government & military organizations). Economic motivation (wages & earnings) were insufficient for coordinating workers across a very large organization before the printing press.

No large empire is possible without writing. It used to be thought that the Inca Empire was the exception to this rule, but that is only because their writing system was so different from any other we know of. They used khipu, a system of knotted cords, as writing and outsiders just didn’t understand it until recently. So now we know that no large empire has ever been managed without writing.

One reason why southern US states banned teaching slaves to read was that literacy is power. Throughout modern history, it is usually educated individuals who have led political revolutions because they have more access to knowledge that helps organize groups and they have better communication ability for mobilizing people.

Mass democracy is a very new thing in the history of the world. There were zero nations where a majority of the adult population could vote in 1900. Today the majority of the nations of the world at least aspires to have universal suffrage and this is the legacy of the printing press. Without printing, there could be no mass democracy because mass democracy requires mass communication. Before the printing press, decisions could only be made by a group of people that was small enough that they could be in the same physical space and hear each other when they yell. In theory, the Roman Colosseum could have enabled a democracy of about 50,000 that could hear an orator screaming in the middle, but ironically, there is no evidence that the Colosseum was ever used for political speeches. Instead, the machinery of democracy took place just outside the Colosseum in the Forum which was a remarkably small, flat, rectangular plaza which would have limited communication to relatively small groups and in the spartan Ovile which was named after the wooden sheep pens that it resembled. At the end of the Roman Republic a larger structure had been in construction for voting, the saepta Iulia, but the importance of voting was greatly diminished after the fall of the Republic and although in theory the space is estimated to have had the capacity to hold more than 30,000 people, it would have been impossible for them all to communicate in the din of a dark, crowded ballroom with voices echoing off of the stone ceiling and well over 60 large stone pillars. Compared with the Colloseum or the Parthenon, it would have been a miserable space for organizing large groups to try to undertake cooperative decision making because it had terrible acoustics and lines of sight.

Similarly, in Athens, the Theatre of Dionysus was the largest theater and could seat up to up to 17,000 people for mass communication, but again there is no evidence that it was used for democratic purposes. Instead, the Athenian assembly met in a park on Pnyx Hill, a 6-minute walk away, with a capacity of only about 6,000 to 13,000 people and much worse acoustics.

Before the printing press, there is no hard evidence that any vote ever extended to even 25,000 people and most democracies only relied on a fraction of that number actually casting a ballot. The major problem was mass communication. There was no point trying to attempt political communication in a Colosseum or large theater because it only took a few noisy people to block mass oral communication so it was just as well to campaign in relatively small groups in a forum or a park and that is why voting took place in such places rather than in the structures that were built to allow everyone in a crowd to see and hear the people on the stage.

The printing press didn’t immediately create mass democracy because it first had to create mass literacy:

And before the printing press created mass democracy, it created a revolution in constitutional government. As Jill Lapore wrote in a review of Linda Colley’s book about constitutions:

Laws govern people; constitutions govern governments. Written (or carved) constitutions, like Hammurabi’s Code, date to antiquity, but hardly anyone read them (hardly anyone could read), and, generally, they were locked away and eventually lost. Even the Magna Carta all but disappeared after King John affixed his seal to it, in 1215. For a written constitution to restrain a government, people living under that government must be able to get a copy of the constitution, easily and cheaply, and they must be able to read it. That wasn’t possible before the invention of the printing press and rising rates of literacy. The U.S. Constitution was printed in Philadelphia two days after it was signed, in …a newspaper that cost four pence…

One overlooked factor that distinguished the [US constitution from earlier constitutions like Russia’s] Nakaz… is how quickly, easily, and successfully the American document was circulated. There were no newspapers in Russia, and no provincial presses. By contrast, anyone who wanted a copy of the U.S. Constitution could have one, within a matter of days after the convention had adjourned.

…[The importance of the press for a successful constitution is why] constitutions guarantee freedom of the press. In the nearly six hundred constitutions written between 1776 and about 1850, the right most frequently asserted—more often than freedom of religion, freedom of speech, or freedom of assembly—was freedom of the press. Colley argues, “Print was deemed indispensable if this new technology was to function effectively and do its work…”

Nick also discusses how printing and culture are intertwined:

Printing was invented in the middle of the 15th century. Books were cheap by the end of that century. Thereafter they just got cheaper. At first books printed en masse what scribes had long considered to be the classics. Eventually, however, books came to contain a wide variety of useful information important to various trades. For example, legal cases became much more thoroughly recorded and far more easily accessible, facilitating development of the common law. Similar revolutions occurred in medicine and a wide variety of trades, and undoubtedly eventually occurred in the building trades that were the source of Clark’s data.

Printing played a crucial role in the Reformation which saw the schisms from the Roman Church and the birth in particular of Calvinism. The crucial thing to observe is that, while per Clark the gains from investment in skills did not increase relative to unskilled labor, with the availability of cheap books and with the proper content the costs of investing in the learning did radically decrease for many skills. Apprenticeships that used to take seven years could be compressed into a few years reading from books (much cheaper than bothering the master for those years) combined with a short period learning on the job. This wouldn’t have been a straightforward process as it required not just cheap books with specialized content about the trades, but some redesigning of the work itself and up-front investment by parents in their children’s literacy. Thus, it would have required major cultural changes. That is why, while under my theory cheap books were the catalyst that drove mankind out of the Malthusian trap, many institutional innovations, which took over a century to evolve, had to be made to take advantage of those books to fundamentally change the economy.

Probably the biggest change required is that literacy entails a very large up-front investment. In the 17th century that investment would have been undertaken primarily by the family. Such an investment requires delayed gratification — the trait Weber considered crucial to the rise of capitalism and derived from Calvinsim. However, Calvinist delayed gratification under my revised theory didn’t cause capitalism via an increased savings rate, as Weber et. al. postulated, but rather caused parents to undertake a costly practice of investing in their children’s literacy. Once that investment was made, the children could take advantage of books to learn skills with unprecedented ease and to skill levels not previously possible. So the overall investment in skills did not increase, but instead the focus of that investment shifted from long apprenticeships of young adults to the literacy of children. At the same time, the productivity of that investment greatly increased, and the result was overall higher productivity.

Protestants, and in particular sects like the Quakers derived from Calvinism, plaid a leading role in the early industrial revolution in England. For example the Quaker Darby family pioneered iron processing techniques and the use of iron for railroads and in architecture.

Investment in literacy would have both enabled and been motivated by the famous Protestant belief that people should read the Bible for themselves rather than depending on a priest to read it for them. This process would have started in the late 15th century among an elite of merchants and nobles, giving rise to the Reformation, but might not have propagated amongst the tradesmen Clark tracks until the 17th century. It is with the spread of Huguenot, Puritan, Presbyterian, etc. literacy culture to tradesmen that we see the 17th century revolution in real wages and the first major move away from the Malthusian curve.

Literacy took off in Europe after the printing press, but it still took a couple centuries:

No nation in Western Europe had a literacy rate above 10 percent in 1500, but by 1800 it was above 50 percent in Great Britain and the Netherlands, and between 20 percent to 40 percent in most other parts of Western Europe.

Max Weber famously theorized that the Protestants pioneered the industrial revolution and got rich sooner than the Catholic regions of Europe because he said the Catholics were lazy and the Protestants were more industrious. A less chauvinistic and scientifically measurable theory would be that the Protestants believed that they must learn to read the Bible and developed literacy to satisfy their religious duty whereas many Catholics believed that the church should interpret the Bible.

For example, in Germany after the printing press (red line), there was much more activity in publishing Protestant religious media (graph on left) than Catholic media (shown on the right).

The amount of literacy and printing seems to be a better predictor of industrialization than religious sect because literacy helps explain why northern Italy, a Catholic area, industrialized earlier than surrounding regions and why Scandinavia didn’t industrialize early despite being Protestant. Northern Italy actually had the largest demand for books in the world in the 1400s despite being Catholic. Industrialization tended to favor areas that developed printing industries:

Jeremiah Dittmar created these maps in his study of the effect of the printing press on economic growth. He found that cities that adopted the printing press had a 60 percentage point growth advantage between 1500-1600.

The movable type printing press was developed by Johannes Gutenberg and his business partners in Mainz, Germany around 1450. Printing was from the outset a for-profit enterprise… The key innovation in printing – the precise combination of metal alloys and the process used to cast the metal type – were trade secrets. The underlying knowledge remained quasi-proprietary for almost a century. The first known “blueprint” manual on the production of movable type was only printed in 1540. Over the period 1450-1500, the master printers who established presses in cities across Europe were overwhelmingly German. Most had either been apprentices of Gutenberg and his partners in Mainz or had learned from former apprentices. Thus a limited number of printers brought the technology from Mainz to other cities… The restrictions on diffusion meant that cities relatively close to Mainz were more likely to receive the technology other things equal… Historians observe that printing diffused from Mainz in “concentric circles” (Barbier 2006). Distance from Mainz was significantly associated with early adoption of the printing press,

The big anomaly on this map would seem to be England because that was the birthplace of the biggest revolution in economic growth, the industrial revolution, despite having almost zero printing industry in 1500. But printing was slow to spread in the early decades because the new technologies were guarded by insiders as trade secrets and it only spread when former employees or family members left one business to start another. The above map only shows the spread of printing in its first fifty years through 1500 before printing spread to England and soon took off there. England could not have led the industrial revolution if a thriving printing industry had not first revolutionized English society.

England soon caught up and along with the Netherlands, it became one of the literacy pioneers by 1650 according to Joseph Henrich who writes about how religion shapes culture:

The historical connection between Protestantism and literacy is well documented… Even as late as 1900, the higher the percentage of Protestants in a country, the higher the rate of literacy. In Britain, Sweden, and the Netherlands, adult literacy rates were nearly 100 percent. Meanwhile, in Catholic countries like Spain and Italy, the rates had only risen to about 50 percent. Overall, if we know the percentage of Protestants in a country, we can account for about half of the cross-national variation in literacy at the dawn of the 20th century…

The Protestant commitment to broad literacy and education can still be observed today in the differential impacts Of Protestant vs. Catholic missions around the globe. In Africa, regions that contained more Christian missions in 1900 had higher literacy rates a century later. …regions with early Protestant missions are associated with literacy rates that are about 16 percentile points higher on average than those associated with Catholic missions. Similarly, individuals in communities associated with historical Protestant missions have about 1.6 years more formal schooling than those around Catholic missions. These differences are big, since Africans in the late 20th century had only about three years of schooling on average, and only about half of adults were literate. These effects are independent of a wide range of geographic, economic, and political factors, as well as the countries’ current spending on education, which itself explains little of the variation in schooling or literacy… [Protestant missions had a particularly big impact on women’s literacy and the] impact of Protestantism on women’s literacy is particularly important, because the babies of literate mothers tend to be fewer, healthier, smarter, and richer as adults than those of illiterate mothers.

As you can see in Henrich’s graph below, Protestant nations achieved mass literacy earlier than predominantly Catholic or Orthodox Christian nations.

After the Protestant Reformation began in 1517, Protestant areas developed universities that were more secular than Catholic universities and focused more on secular topics like science, engineering, finance, law, and math compared with Catholic areas which maintained a more traditional religious focus.

The change in educational focus towards secular employment would have been a big advantage for bringing the economic growth of the industrial revolution.

Whereas it is true that Protestant areas achieved higher literacy than Catholic areas on average, there is also enormous variance within both groups. For example, the Brethren of the Common Life and the Cistercians promoted work ethic and the Jesuits promoted schooling and literacy about as ardently as many Protestent sects whereas some Protestants like the Amish rejected science and technology and discouraged education beyond grade school.

The United States was founded by religious sects that placed a high value on literacy to read the Bible. Early settlers not only started printing presses, but also numerous libraries. More than 2100 libraries were created between 1796 and 1840. In New England they already had tax-financed public schooling in the 1700s and the national postal system was set up to amplify the power of writing at the beginning of the revolutionary war.

Similarly, printing presses have had an influence in Africa. Cagé & Rueda found that,

African regions where Protestant missionaries were active had indigenous newspapers a century before other regions… this difference has had lasting effects. Proximity to a mission that had a printing press in 1903 predicts newspaper readership today. Population density and light density (a proxy for economic development) is also higher today in regions nearer to missions that had printing presses. The results suggest that a well-functioning media – not Protestantism per se – was important for development.

In the graph below, there were many, many Protestant missions (denoted by a “+”), but very few printing presses (red circles), but the printing presses seem to have a separate effect from religion.

Unfortunately, Africa prints less than 2% of global books and most of that is in the relatively developed country of South Africa. African literacy is also hampered by the fact that there are over 1,500 different languages spoken in the home and it is not profitable to publish in most of the native languages with such a limited market. Most publishing is in the European languages of former colonists which are not spoken fluently by everyone. That linguistic divide is an extra barrier to literacy and the culture of the book.

Like some Protestant sects, many Jewish sects thrived economically in European cities after the rise of printing and they too had a longstanding religious tradition that achieved near universal literacy among males. This helps explain why the Jewish diaspora is overly represented in science, literature, the arts and why Jewish communities have tended to earn incomes that are well above average. In modern times, some Asian diasporas have duplicated this cultural focus on education and achieved a similar level of economic success.

Literacy causes physiological changes in brain structure and neurology

Joseph Henrich documents biological differences in the brains and cognitive abilities of literate people versus non-literate which impacts basic cognitive features like memory, visual processing, and facial recognition:

- Specialized left ventral occipito-temporal region for literate people.

- Thickened corpus callosum, the information highway that connects the left and right hemispheres of your brain.

- Altered Broca’s area and other parts of the prefrontal cortex.

- Improved verbal memory.

- Shifted facial recognition processing to the right hemisphere. Pre-literate humans process faces almost equally on both the left and right sides of their brains.

- Diminished ability to identify faces, probably because the left ventral occipito-temporal region that usually specializes in facial recognition is dedicated to reading.

- Reduced tendency from holistic visual processing in favor of analytical processing.

Physiological changes in neurology must also change culture and economies.

Marshal McLuhan argued that all communication media changes how we think. When the telegraph was in its heyday, it caused people to think, write and speak more telegraphically in short, succinct phrases with newly invented words and acronyms that were invented to save money in telegraphic messages which paid by the letter. The greater accuracy of printing led to a renaissance in mathematics because ideas could be shared widely and more importantly they were shared much more accurately. The first major printed mathematics text popularized Arabic numbers and other new mathematical symbols which finally replaced Roman numbers in Europe and converted mathematics from a literary endeavor into a system of abstract symbolic logic. Arabic numerals (math) also replaced Latin as a lingua franca in international science.

In the days when manuscripts were hand-written, authors of mathematics texts avoided any use of the abstract symbols they used to do calculations—other than the basic numerals—because they could not rely on accurate copying of formulas and equations by the scribes who made copies. But with print, there was nothing that prevented them having entire pages consist of little else than formulas and equations. (The reason people today associate mathematics with symbols is a result of the printing press. Before then, mathematics was a subject presented in prose.)

Writing technology has also caused a divergence between how Chinese speakers and English speakers speak and think. Chinese people do not use an auditory part of the brain for reading and that shortcut means that they can read faster than people reading alphabetic languages. Ironically, modern Chinese text input also relies upon sound, so there is a return to the connection the phonetic. (Tom Mullaney argues that Chinese text input is also now faster on computers than English because Chinese computers have much better predictive autocompletion than is available for English.)

Because the English language uses phonetic writing it is easy to coin new words and disseminate them whereas Chinese words are much more difficult to coin because Chinese writing is logographic. The difficulty of memorizing thousands of different characters means that Chinese reading takes more time to learn. Chinese reading is so much more cognitively demanding that Chinese readers are going to be less receptive to needing to learn new words. Plus the pronunciation of a word is completely separate from the writing of a word, so people who would coin new words would have to teach two different kinds of information separately whereas alphabetical writing incorporates the phonetics directly in the writing. The difficulty is compounded by the fact that there are people who speak completely different languages and have completely different pronunciation for exactly the same written words who use the same Chinese writing system so it is impossible to define a single pronunciation for any given Chinese word that works for all readers.

As a result of these complexities, there are only about 7,000 characters that are used in modern Chinese as unique monosyllabic words. It is estimated that those characters are combined into a total of about 106,230 compound words, but the typical college graduate only recognizes about 4,000 to 5,000 characters, and 40,000 to 60,000 compound words. In contrast, there are many more words in alphabetic languages despite all other languages having fewer native speakers and a much younger writing system.

…the changes brought about by the printing press, and other information media, may have re-shaped our minds. Books laid the foundations for “deep reading” and, through that, deeper and wider thinking. Technology was, quite literally, mind-bending… this re-wiring stimulated the slow-thinking, reflective, patient part of the brain identified by psychologists such as Daniel Kahneman.

The most reliable way to improve brain function is much like how we improve the functioning of muscles: long-term deliberate practice. It is hard to imagine a better tool for changing brain function than books which require years of practice before they can be used fluently and then readers spend hours at a time in an altered mental state using them. Actually, the TV and the cellphone may have had a bigger effect upon brain function, but it is likely to be a negative effect because they are more passive and require so little concentration that many people use them while attempting to ‘multitask’. Books require too much concentration to multitask and train people to think more deeply rather than shallowly like browsing social media.

The internet is more addictive than books because it engages more of our senses with colorful videos and sounds and because the corporations that run most of the internet have turned us all into lab rats pressing levers to get immediate gratification. The corporations are constantly testing how to get us to be more engaged with content so they can sell data about our personal habits and influence us on behalf of advertisers. Activities like sustained, uninterrupted reading are bad for selling products. Selling and harvesting information about our triggers requires frequent interruption to encourage interaction with the various levers (links) they are testing.

As Steven Pinker said in Enlightenment Now:

The supernova of [published, mass-media] knowledge continuously redefines what it means to be human… Though unlettered hunters, herders, and peasants are fully human, anthropologists often comment on their orientation to the present, the local, the physical. To be aware of one’s country and its history, of the diversity of customs and beliefs across the globe and through the ages, of the blunders and triumphs of past civilizations, of the microcosms of cells and atoms and the macrocosms of planets and galaxies, of the ethereal reality of number and logic and pattern—such awareness [which originally came about through printing] truly lifts us to a higher plane of consciousness.

Printing changed how we organize information

Although alphabetical order was invented before printing, the idea of using it to index information did not take off until the printed codex (book) was invented and page numbers were added. Suddenly it became possible to nearly instantly look up all sorts of information by creating indexes and Dennis Duncan wrote an entire book about how indexing changed life. Suddenly we could have dictionaries and encyclopedias and tables of contents and library catalogs and the biggest index of all, Google’s search engine, which is merely a digital extension of the humble book index.

Information used to spread VERY slowly

It is hard to imagine how slowly information used to spread before the modern era. Goods used to spread much faster than information. For example, for thousands of years, silk was traded across thousands of miles along the silk road, but the tacit knowledge about how to produce silk didn’t travel. The surprising complexities of rice cultivation also took thousands of years to make it from Asia to Europe and Africa where it revolutionized diet after the late 1400s beginning in Italy. Although corn spread around the world rapidly, the nixtamalization process that made it much more nutritious never made it out of North America.

One reason why revolutionary know-how about silk, rice, and nixtamalization didn’t spread across oceans is that tacit knowledge is hard to write down, but it isn’t impossible and when the transactions costs of sending information are high and the extent of the market is small, it just isn’t worth the effort for anyone to try to communicate the information. Before the printing press, books were extremely heavy (due to the aforementioned primitive paper technologies) and easily damaged by dampness. Because they were extraordinarily valuable and easily damaged, they were rarely transported away from the places where they were created. Even in the early decades after the printing press brought down costs, According to Flood (1987, p.25), they were still not circulated widely outside of the towns where they were printed.

Similarly, although the printing press spread rapidly across the European cultures, it took hundreds of years for Book Culture to spread to many parts of Asia and Africa. Without Book Culture, they couldn’t develop corporations, science, democracy, nor the industrial revolution. But in the past half century, reading and literacy has finally transformed almost the entire globe and almost all poor nations have been catching up with rich countries in economic development for at least three decades now.

Still today in most developing nations public libraries are extremely rare or completely absent and bookstores are few and carry few titles. The printing-press revolution has only finally reached most of the world in the past century and because it is coming at about the same time as the cellular internet revolution, it is going to be an information revolution on steroids.

Conclusion

Francis Bacon said that the world’s most important inventions in 1620 were printing, gunpowder and the compass. All were invented in East Asia so it is surprising that Europeans used them to conquer the world. Although printing was invented in Asia with the oldest surviving printed work probably dating back before 751, Gutenberg’s printing press was a major advancement and that advance alone may explain why Europeans conquered the world rather than Asians.

Although computers and the internet have not yet increased measured GDP growth, they are revolutionizing society. Similarly, the printing press revolutionized society and eventually directly contributed to the industrial revolution even though printing itself was never more than a minuscule part of GDP. Printing caused numerous revolutions in society.

- Religious revolution ← protestant reformation

- Scientific revolution ← the rest of the industrial revolution depended on this. The enlightenment was based upon printed communication.

- Cognitive revolution. Literacy changes how people think. The extra challenge of written syntax pushes writers to be more logical and memorization was extremely important before literacy. The printing press nearly eliminated professional storytellers who specialized in reciting great works of oral tradition like Homer’s Illiad or Beowulf. Literacy completely changes how people think and alters brain anatomy. The written word is the most efficient way to communicate many kinds of information between humans.

- Political revolution

- Constitutional law: Before the printing press, most democracies didn’t have a constitution. Today, even many non-democracies have constitutions that constrain government.

- Mass democracy. Although most people think about democratic federal and local governments when they think about democracy, the corporation is also an example of a revolutionary form of mass democracy for the plutocratic governance of business which couldn’t have arisen until after the spread of mass communication.

- Capitalism. The printing press made capitalism possible because capitalism requires standardized forms of information in order to be able to create meaningful rule of law, financial markets (stock markets, etc.), corporations, contracts (insurance, etc.), and property rights. There was no point creating intellectual property rights before mass media was invented and so the first intellectual property wasn’t invented until 1710 when copyright was first created in England.

- Accounting standards couldn’t be developed and standardized without printed books to communicate exactly how to standardize bookkeeping and the literacy to adopt the standards.

- Printing increased the speed, durability, and accuracy of communication and dramatically reduced the cost of storing and transmitting information.

- Colonial revolution. Columbus might not have sailed across the ocean if the elites of Europe hadn’t been reading about the science of sailing west to get to China. Then the conquistadors would not have been able to learn from previous conquests and discoveries without cheap written communication. There would not have been sufficient communication power to organize the corporations that colonized India, Indonesia, New England, and elsewhere. And Europe’s armies would not have been backed by the industrial weaponry and infrastructure needed to take over the world.

- Ageist revolution. Elders were revered in every preliterate civilization partly because they had the most knowledge and wisdom. Mass literacy meant shifting social prestige away from the most experienced people because younger generations could seek wisdom from books instead. Today there is more shift from asking knowledgeable people towards asking Google or Alexa! (Elders were also more revered for most of history because there were so few elders due to high mortality and high fertility.)

- Industrial revolution. It would not have been possible without mass literacy and mass communication.

Ironically Gutenberg effectively went bankrupt by 1456, only about six years after he had starting printing. When he died in 1468, he was not seen as particularly important relative to local church leaders or nobility and his grave is now lost. It was only much later that historians developed enough perspective to realize how important his invention had been.

[…] because new information technologies has been helping knowledge spread faster. In the 1500s the printing press opened up the age of discovery and the industrial revolution for European nations which led them to grow much faster than nations […]

[…] as mass democracies could not exist before the spread of literacy and cheap communication that Gutenberg’s printing press brought about, corporations were impossible for all of history for the same reason. It was simply impossible to […]

During Liao Dynasty, the Khitans invented the first stone movable type in 921, then wooden one in 938, ceramic one in 974, bronze alloy one in 1000. Song took the knowledge from them and invented a piece of particular equipment for the ceramic and wooden ones, while the Goryeo (now Korean) took the bronze alloy one and invented another equipment for that.

Thanks for your comment. Do you have a source I could look up?

[…] advent of mass communication technologies beginning with the printing press have made it easier to influence and coordinate masses of people through verbal persuasion too. […]

[…] The innovation that allowed corporations to dramatically expand was the printing press. A corporation is a form of mass democracy and just as democratic participation in government is limited in scope by communication technologies, so is democratic participation in investing and managing a private company. […]

[…] it, and the new pronoun for non-gendered people would still be pronounced the same way. But it is difficult to add written words to the Chinese vocabulary and one of the most popular proposed pronouns for the nongendered human […]

[…] Without abundant mass communication, mass democracy is impossible, and prior to the printing press, we do not have any evidence for any election surpassing even 25,000 voters. Unfortunately, ancient societies never bothered to record precise vote counts (which demonstrates how little they cared about this), so we can only estimate based on the time spent voting (given our knowledge of voting practices) and the capacity of the physical spaces used for voting: […]