Updated January 9, 2024

Julie Beck wrote that

In America, we treat the mouth separately from the rest of the body, a bizarre situation that Mary Otto explores in… Teeth: The Story of Beauty, Inequality, and the Struggle for Oral Health in America… Specializing in one part of the body isn’t what’s weird—it would be one thing if dentists were like dermatologists or cardiologists. The weird thing is that oral care is divorced from medicine’s education system, physician networks, medical records, and payment systems, so that a dentist is not… a special kind of doctor, but another profession entirely.

Otto says that this state of affairs can be traced back to a historical accident in 1840 when some dentists established the first dental college in Baltimore. They approached the physicians at the University of Maryland to suggest that it be incorporated into the medical school, but they were rejected and so they started their own parallel system of education, research, financing, medical records, and licensure.

This doesn’t make much sense because dental health is an integral part of overall health and Olga Khazan says that

since the beginning of time, dentistry and medicine have been considered inherently distinct practices. The two have never been treated the same way by either the medical system or public insurance programs. But as we learn more about how diseases that start in our mouths can ravage the rest of our bodies, it’s a separation that’s increasingly hard to rationalize.

More than a million people go to emergency rooms for dental care each year because they lack other options, but emergency rooms are terrible places to get dental care and few people have useful dental insurance except people with great private employer benefits and children on Medicaid.

There have been some attempts to merge the two systems, but dentists prefer to stay independent because the dental associations value the power they get from their professional autonomy. It gives dentists more control.

For example, when dental hygienists can practice independently from dentists, they can earn more money and charge less for cleanings and dental health improves. As Matt Yglesias wrote:

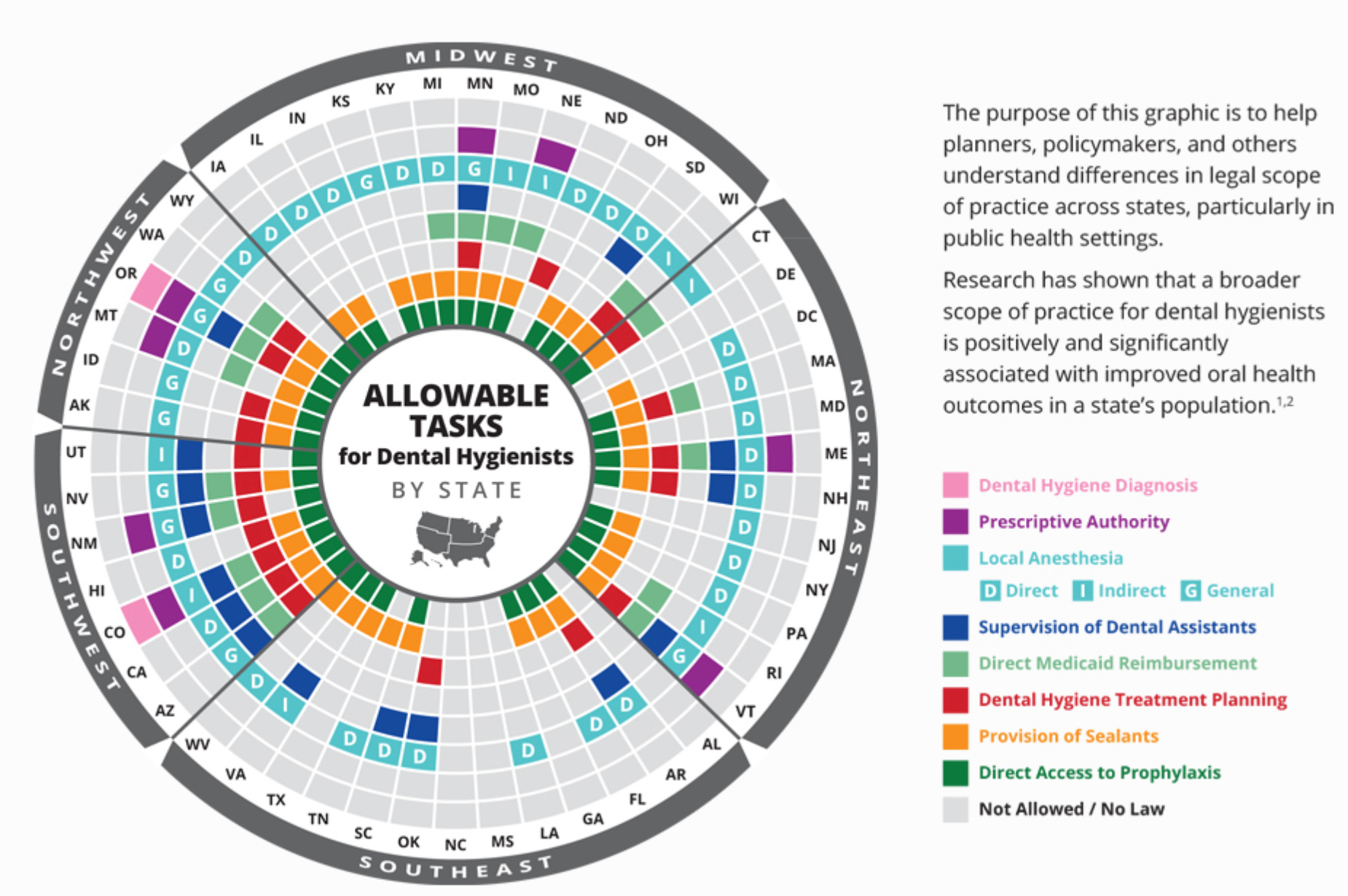

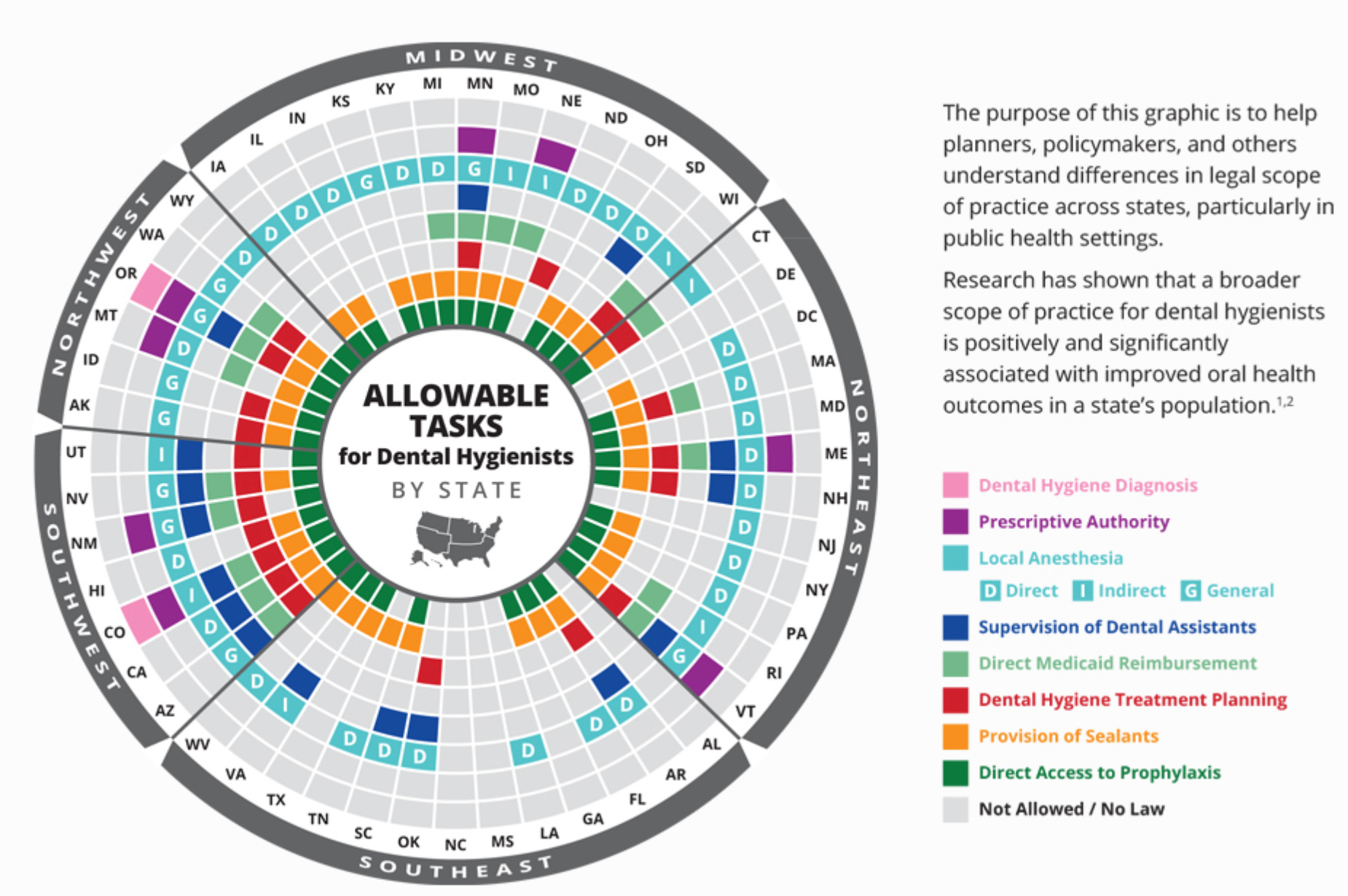

the form of dental care that most people need is a regular cleaning, and perhaps some x-rays just to check for problems. And if you’ve ever been to a dentist’s office, you’ve probably noticed that the dentist does not actually do this work and that it is done instead by a dental hygienist. One might think that since the work of a routine dental appointment is done by a hygienist rather than a dentist, a standard oral health appointment would simply be with a hygienist who lets you know if you need more specialized dental care. In reality, however, “scope of practice” rules pretty strictly limit which services a hygienist can provide, and only in Colorado and Oregon can hygienists perform diagnostic work…

There is, notably, no real …pattern to this patchwork of regulations, which is usually a sign that you are dealing with shady interest group politics rather than any plausible theory of public interest…

[The variation in regulation allows us to test what works best.] The Air Force assesses the dental health of its incoming recruits, which researchers used to gauge state-by-state variation. They find that stricter [limits on hygienist practice] are associated with higher prices for consumers of dental services and worse oral health outcomes. A different team looked at state-by-state variation in the need to have teeth removed due to decay, and found that “more autonomous dental hygienist scope of practice had a positive and significant association with population oral health in both 2001 and 2014.”

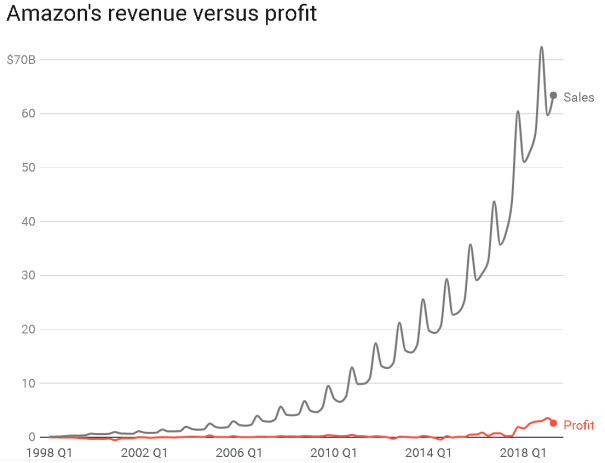

…Where hygienists are allowed to be self-employed, their incomes rise by about 10 percent, while the incomes of dentists fall. The median hourly wage for dental hygienists is about $39 per hour — higher than the national average, but much lower than for dentists, so this is a progressive economic change.

When dental hygienists can practice independently from dentists, everyone wins except dentists who earn 16% less according to one study. Max Ehrenfreund found that

Dentists in some places are so well compensated that they earn more than the average doctor. According to a 2012 report in The Journal of the American Medical Association, the average hourly wage of a dentist in America is $69.60 vs. $67.30 for a physician.

Although I have been fortunate to have mostly found honest, hardworking dentists who care about my family’s oral health, many dentists have been padding their incomes by using what Jeffrey H. Camm called “creative diagnosis” in a commentary published by the American Dental Association (also known as “supplier-induced demand” in the economics literature). Alison Seiffer wrote about this practice:

My household’s level of confidence in dentistry is at an all-time low. About six months ago, my dentist informed me that my “bunny teeth” were likely getting in the way of my professional success, a problem he could correct with a (pricey) cosmetic procedure. If I let him fix my teeth, he told me, he was sure I would start “dressing better.” A few months later, my husband scheduled a basic cleaning with a new dentist. Once they had him in the chair and looked at his teeth, they informed him that the regular cleaning wouldn’t do at all: He would need to reschedule for an $800 deep cleaning. No thanks.

We were convinced we must look like suckers—until I came across an op-ed in ADA News, the official publication of the American Dental Association. The article, by longtime pediatric dentist Jeffrey Camm, described a disturbing trend he called “creative diagnosis”—the peddling of unnecessary treatments. William van Dyk, a Northern California dentist of 41 years, saw Camm’s op-ed and wrote in: “I especially love the patients that come in for second opinions after the previous dentist found multiple thousands of dollars in necessary treatment where nothing had been found six months earlier. And, when we look, there is nothing to diagnose.”

…Poking around, I found plenty of services catering to dentists hoping to increase their incomes. One lecturer at a privately operated seminar called The Profitable Dentist ($389) aimed to help “dentists to reignite their passion for dentistry while increasing their profit and time away from the office.” Even the ADA’s 2014 annual conference offered tips for maximizing revenue… more and more young dentists are taking jobs with chains, many of which set revenue quotas for practitioners. This has created some legal backlash: In 2012, for example, 11 patients sued (PDF) a 450-office chain called Aspen Dental, claiming that its model turns dentists into salespeople. Some corporate dentists appear to have crossed the line into fraud. In 2010, Small Smiles, a venture-capital-owned chain with offices in 20 states, was ordered to refund $24 million to the government after an investigation found that its dentists had been performing unnecessary extractions, fillings, and root canals on children covered by Medicaid. A new lawsuit alleges that some toddlers it treated underwent as many as 14 procedures—often under restraint and without anesthesia. …Several other pediatric dentistry chains have been sued over similar allegations. ….

This isn’t a new problem although it might be getting worse. As America’s teeth have gotten healthier and need less dental treatment due to better brushing and fluoride, dentistry has found other ways to boost revenues at a double-digit growth rate.

One way dental offices have increased revenues is by offering a more spa-like experience with aromatherapy, nicer decor, Netflix, weighted blankets, hoise-cancelling headphones, massage, cake, and other services that make a dental visit a more pleasant experience and allow them to charge a premium.

Unfortunately, another way they have increased revenues is by tricking patients into getting excessive treatments. Readers Digest did an experiment in 1997 in which award-winning journalist William Ecenbarger visited 50 dentists in 28 states and wrote an article entitled, “How Honest Are Dentists?” For the baseline, he hired a panel of expert dentists from a dental school to tell him what they thought he should get. They all agreed that he should get one crown and he might need a filling although some thought he could wait and see. They estimated that the total cost for his dental care should be between $500 and $1500. Then he went out into the wild dental marketplace, and he got wildly varying opinions. Indeed 79% of dentists exceeded the recommendations of the panel of experts and creatively diagnosed urgent problems that would generate more revenues. At the same time, 30% missed the real molar problem that needed capping and more than 72% failed to do two low-profit preventative screenings that the ADA recommends:

- 72% neglected periodontal screening

- 58% neglected oral-cancer screening

Here is a chart showing the six most egregious examples of “creative diagnosis”. Note that two of the dentists wanted to do 28 crowns!! That would mean crowning every single tooth if (as is likely) he had already had his wisdom teeth extracted.

Location

(# most expensive)

|

# of crowns (C) and fillings (F)

|

Total estimate

|

| Panel of Experts |

1C, 1F (maybe) |

$500-$1,500 |

| (6) Englewood, OH |

11C, 5F |

$8,347 |

| (5) Seattle, WA |

17C |

$10,735 |

| (4) Memphis, TN |

28C |

$13,440 |

| (3) Albuquerque, NM |

22C |

$14,445 |

| (2) Salt Lake City, UT |

28C |

$19,402 |

| (1) New York, NY |

21C |

$29,850 |

Oddly, although this research was famous and generated lots of responses on the internet, Reader’s Digest doesn’t have anything about it on their own website! They seem to have buried one of their most important and popular pieces of investigative journalism. I wonder who influenced that decision!?

Although I have found great dentists, I have also had some who over diagnosed. One dentist wanted to replace all of my teeth and my wife’s teeth with implants (like you frequently see advertised on the internet) and he told my wife that she has ugly “buck teeth” that she deserves to have replaced. Three other dentists completely invented cavities that no later dentist has seen. And even good dentists frequently exceed the ADA recommendations. For example, most dentists encourage 6-month checkups whereas the ADA thinks most people are of low risk and only need annual checkups. Dentists also overdo X-rays. The ADA recommends waiting 2-3years between X-rays if there are no cavities whereas most dentists want (profitable) X-rays every visit.

In addition Joseph Stromberg suggests that dental patents should beware of:

1. Dental practices that advertise and offer deals. As he says,

The reason for this is that advertising-driven offices often use deals as a tool to get patients in the door and then pressure them to accept an expensive treatment plan, whether they need work done or not. Oftentimes, they’re corporate-owned chains, like Aspen Dental. “These big chains are kind of dental mills,” Mindy Weinman said. “They’re the ones that give you the free cleaning, and the free exam, then they tell you that you need $3,000 worth of [unnecessary] dental work.”

PBS also wrote about Aspen Dental’s practice of luring patients with low prices and then selling thousands of dollars of useless drilling and filling.

2. A new dentist who prescribes more treatments than usual.

3. Replacing old fillings

4. Veneers. These cash cows are almost always unnecessary and purely for cosmetic purposes, but they can make teeth problems worse in the long run.

5. Fluoride treatment or sealants for adults or special fluoride toothpaste. Kids benefit a lot from fluoride sealants (as noted below), but there is rarely any benefit for adults and sealants can actually weaken the teeth through the etching process.

6. Dentists who don’t show you evidence of problems on your x-rays. Of course, most dentists take way more x-rays than is healthy for their patients, but if they do take them and tell you that you have a problem, they should show you the problem on the x-ray and let you have a copy of the x-ray. It is legally your property even though some dentists don’t like to let you see them. As Stromberg wrote:

Virtually all honest dentists will gladly show you X-rays of your teeth that contain evidence of the work you need. “X-rays, legally, are your property. A dentist can charge for them, but they have to share them with you,” Mindy Weinman said.

You won’t necessarily be able to see evidence of every single type of problem in an X-ray, but many of them should be apparent. A dark spot or blemish, in general, corresponds to a cavity. And in general, the dentist should be willing and able to explain why you need certain procedures, both by using X-rays and other means.

But regardless of what the X-rays show, if you’re skeptical of the treatment a dentist is prescribing — especially if it’s your first visit to the practice, and they’re recommending far more work than you’re ever needed before — the best response is to get a second opinion. This was mentioned to me by every dentist I spoke with, along with the American Dental Association.

I have gotten a second opinion twice and both times I saved hundreds of dollars by avoiding completely unnecessary drilling and filling. It is extremely easy for healthcare providers to sell people on unnecessary treatments because they have more information than patients and they can easily motivate sales by gently stoking fears of future pain or illness.

For more stories about creative diagnosis at dental offices, see Ferris Jabr’s excellent essay. Jabr also tells that dentists have not been doing much scientific research, so a lot of what they do is based on dark-age evidence.

The Cochrane organization, a highly respected arbiter of evidence-based medicine, has conducted systematic reviews of oral-health studies since 1999. In these reviews, researchers analyze the scientific literature on a particular dental intervention, focusing on the most rigorous and well-designed studies. In some cases, the findings clearly justify a given procedure. For example, dental sealants—liquid plastics painted onto the pits and grooves of teeth like nail polish—reduce tooth decay in children and have no known risks. (Despite this, they are not widely used, possibly because they are too simple and inexpensive to earn dentists much money.) But most of the Cochrane reviews reach one of two disheartening conclusions: Either the available evidence fails to confirm the purported benefits of a given dental intervention, or there is simply not enough research to say anything substantive one way or another.

At the same time as some Americans are getting excessive, unnecessary dental care, other Americans lack access because they are too poor or because they live in a rural area where dentists are simply not available. Olga Khazan says that,

About a third of people in the U.S. don’t visit the dentist every year, and more than 800,000 annual ER visits arise from preventable dental problems. A fifth of Maryland residents have not visited a dentist in the past five years… There are about 4,000 designated dentist shortage areas all over the U.S. In some of the worst-affected states, between a quarter and a third of the population lacks access to dental care entirely.

Gabrielle Glasier writes in The Atlantic about

Gabrielle Glasier writes in The Atlantic about