Once upon a time, there were three neighboring families with young children. They all needed babysitting at different times and there was a shortage of reliable professional babysitters in the neighborhood. The neighbors all wanted their children to be able to play with neighboring kids, so they often take turns babysitting for each other. However, the Smith family started babysitting more for the Wilsons than the Wilsons could reciprocate, and the Wilsons would often say ‘we owe you one’ to the Smiths. The Smiths know that they can count on getting the favor returned, but the Wilsons were worried that they would forget so the Wilsons started writing IOUs on scraps of paper to help keep track.

Then the Wilson family’s schedule changed and they could no longer babysit the Smiths anymore. The Smith family had accumulated five IOUs, and the Wilson’s felt bad about not being able to pay them back. Fortunately, the Jones family was available to babysit for the Smiths. The Smiths give them an IOU each time to help keep track because they Smiths’ schedules meant that they weren’t able to pay them back very often. The Joneses accumulated a pile of IOUs.

The Wilsons had been feeling guilty about not doing their part, so they figured out how to rearrange their schedule to babysit for the Wilsons even though they actually owed the Smiths. Naturally, the Wilsons gave them IOUs and the Smiths were surprised to see that they were getting back the very same IOUs that they originally gave to the Smiths. The three families got together and decided to invite other neighboring families to join their babysitting circle and a babysitting coop was born.

This parable illustrates that even with only three families, there is often a coincidence of wants problem that is makes it difficult or impossible to barter between any two people even though there are other people who could fill the wants of both. IOUs (also known as Money) can help solve this coordination problem.

This is also essentially how all money works. In societies with less trust and more potential problems with counterfeiting than a community of friends exchanging the gift of babysitting, some sort of intrinsically-valuable commodity like gold or cigarettes is sometimes also used, but commodity money works exactly the same way as IOUs except for the greater difficulty in creating commodity money (and the greater incentive to intentionally destroy it to use it as a commodity). People accept gold coins in payment merely because they know that lots of other people will feel indebted to whoever has a lot of gold coins.

Paul Krugman has often written about a similar case study that he says changed his life. It was published in the Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking in 1978 and entitled, “Monetary Theory and the Great Capitol Hill Baby-Sitting Co-op Crisis” by Joan and Richard Sweeney.

The Sweeneys tell the story of …a baby-sitting co-op …to which they belonged… Such co-ops are quite common: A group of people (in this case about 150 young couples with congressional connections) agrees to baby-sit for one another… It’s a mutually beneficial arrangement: A couple that already has children around may find that watching another couple’s kids for an evening is not that much of an additional burden, certainly compared with the benefit of receiving the same service some other evening. But there must be a system for making sure each couple does its fair share.

The Capitol Hill co-op adopted one fairly natural solution. It issued scrip—pieces of paper equivalent to one hour of baby-sitting time. Baby sitters would receive the appropriate number of coupons directly from the baby sittees. This made the system self-enforcing: Over [the long run], each couple would automatically do as much baby-sitting as it received in return [because when the parents left the coop, they had to return as many coupons to the coop as they originally received. The coupons were effectively loaned to the parents]. As long as the people were reliable—and these young professionals certainly were—what could go wrong?

Well, it turned out that there was a small technical problem. Think about the coupon holdings of a typical couple. During periods when it had few occasions to go out, a couple would probably try to build up a reserve—then run that reserve down when the occasions arose. [Normally] there would be an averaging out of these demands. One couple would be going out when another was staying at home. But …what happened in the Sweeneys’ co-op was that …the number of coupons in circulation became quite low [because members paid dues in coupons and some coupons got lost.]

As a result, most couples were anxious to add to their reserves by baby-sitting, reluctant to run them down by going out. But one couple’s decision to go out was another’s chance to baby-sit; so it became difficult to earn coupons. Knowing this, couples became even more reluctant to use their reserves except on special occasions, reducing baby-sitting opportunities still further.

In short, the co-op had fallen into a recession.

Since most of the co-op’s members were lawyers, …They tried to legislate recovery—passing a rule requiring each couple to go out at least twice a month. But eventually … More coupons were issued, couples became more willing to go out, opportunities to baby-sit multiplied, and everyone was happy. Eventually, of course, the co-op issued too much scrip, leading to different problems …

If you think this is a silly story, a waste of your time, shame on you. What the Capitol Hill Baby-Sitting Co-op experienced was a real recession. …if you are willing to really wrap your mind around the co-op’s story, to play with it and draw out its implications, it will change the way you think about the world.

…Above all, the story of the co-op tells you that economic slumps are not punishments for our sins, pains that we are fated to suffer. The Capitol Hill co-op did not get into trouble because its members were bad, inefficient baby sitters; its troubles did not reveal the fundamental flaws of “Capitol Hill values” …It had a technical problem—too many people chasing too little scrip—which could be, and was, solved with a little clear thinking. …

…imagine a co-op …when a couple found itself needing to go out several times in a row, which would cause it to run out of coupons—and therefore be unable to get its babies sat—even though it was entirely willing to do lots of compensatory baby-sitting at a later date. To resolve this problem, the co-op [could allow] members to borrow extra coupons from the management in times of need—repaying with the coupons received from subsequent baby-sitting. To prevent members from abusing this privilege, however, the management would probably need to impose some penalty—requiring borrowers to repay more coupons than they borrowed.

Under this new system, couples would hold smaller reserves of coupons than before, knowing they could borrow more if necessary. The co-op’s officers would, however, have acquired a new tool of management. If members of the co-op reported it was easy to find baby sitters and hard to find opportunities to baby-sit, the terms under which members could borrow coupons could be made more favorable, encouraging more people to go out. If baby sitters were scarce, those terms could be worsened, encouraging people to go out less.

In other words, this more sophisticated co-op would have a central bank that could stimulate a depressed economy by reducing the interest rate and cool off an overheated one by raising it.

…imagine there is a seasonality in the demand and supply for baby-sitting. During the winter, when it’s cold and dark, couples don’t want to go out much but are quite willing to stay home and look after other people’s children—thereby accumulating points they can use on balmy summer evenings. …the co-op could still keep the supply and demand for baby-sitting in balance by charging low interest rates in the winter months, higher rates in the summer.

Krugman also wrote about this story in his 2012 book, End This Depression Now! and I found some of the text online with a quick Google search. He begins by giving an example of one of the many anti-Keynesians who do not believe that there could be a problem like the babysitting coop example:

…Here’s Brian Riedl of the Heritage Foundation …in an early-2009 interview with National Review:

The grand Keynesian myth is that you can spend money and thereby increase demand. And it’s a myth because Congress does not have a vault of money to distribute in the economy. Every dollar Congress injects into the economy must first be taxed or borrowed out of the economy. You’re not creating new demand, you’re just transferring it from one group of people to another.

Give Riedl some credit: …he admits that his argument applies to any source of new spending. That is, he admits that his argument that a government spending program can’t raise employment is also an argument that, say, a boom in business investment can’t raise employment either. And it should apply to falling as well as rising spending. If, say, debt-burdened consumers choose to spend $500 billion less, that money, according to people like Riedl, must be going into banks, which will lend it out, so that businesses or other consumers will spend $500 billion more. If businesses …scale back their investment spending, the money they thereby release must be spent by less nervous businesses or consumers. According to Riedl’s logic, overall lack of demand can’t hurt the economy, because it just can’t happen.

…What do we learn from [the babysitting coop] story? If you say “nothing,” because it seems too cute and trivial, shame on you. The Capitol Hill babysitting co-op was a real, …miniature, monetary economy. It lacked many of the features of the enormous system we call the world economy, but it had one feature that is crucial to understanding what has gone wrong with that world economy—a feature that seems, time and again, to be beyond the ability of politicians and policy makers to grasp.

What is that feature? It is the fact that your spending is my income, and my spending is your income. Isn’t that obvious? Not to many influential people. For example, it clearly wasn’t obvious to John Boehner, the Speaker of the U.S. House, who opposed President Obama’s [fiscal stimulus], arguing that since Americans were suffering, it was time for the U.S. government to tighten its belt too. (To the great dismay of …economists, Obama ended up echoing that line in his own speeches.)

The question Boehner didn’t ask himself was, if ordinary citizens are tightening their belts—spending less—and the government also spends less, who is going to buy American products? Similarly, the point that every individual’s income …is someone else’s spending is clearly not obvious to many German officials…

And because the babysitting co-op, for all its simplicity and tiny scale, had this crucial, not at all obvious feature that’s also true of the world economy, the co-op’s experiences can serve as “proof of concept” for …at least three important lessons.

First, we learn that an overall inadequate level of demand is indeed a real possibility. When coupon-short members of the babysitting co-op decided to stop spending coupons on nights out, that decision didn’t lead to any automatic offsetting rise in spending by other co-op members; on the contrary, the reduced availability of babysitting opportunities made everyone spend less.

People like Brian Riedl are right that spending must always equal income: the number of babysitting coupons earned in a given week was always equal to the number of coupons spent. But this doesn’t mean that people will always spend enough to make full use of the economy’s productive capacity; it can instead mean that enough capacity stands idle to depress income down to the level of spending.

This is what happens in a recession when many factories and workers are unemployed.

Second, an economy really can be depressed thanks …failures of [demand] rather than lack of productive capacity. The co-op didn’t get into trouble because its members were bad babysitters, or because high tax rates or too-generous government handouts made them unwilling to take babysitting jobs, or because they were paying the inevitable price for past excesses. It got into trouble for a seemingly trivial reason: the supply of coupons was too low, and this created a “colossal muddle,” …in which the members of the co-op were, as individuals, trying to do something—add to their hoards of coupons— that [everyone simultaneously] could not, as a group, actually do.

This is a crucial insight. The [2008] crisis in the global economy …is, for all the differences in scale, very similar in character to the problems of the co-op. Collectively, the world’s residents are trying to buy less stuff than they are capable of producing, to spend less than they earn. That’s possible for an individual, but not for the world as a whole. And the result is the devastation all around us.

…If we look at the state of the world on the eve of the crisis—say, in 2005–07—we see a picture in which some people were cheerfully lending a lot of money to other people, who were cheerfully spending that money. U.S. corporations were lending their excess cash to investment banks, which in turn were using the funds to finance home loans; German banks were lending excess cash to Spanish banks, which were also using the funds to finance home loans; and so on. …And because your spending is my income, there were plenty of sales, and jobs were relatively easy to find.

Then the music stopped. Lenders became much more cautious about making new loans; the people who had been borrowing were forced to cut back sharply on their spending. And here’s the problem: nobody else was ready to step up and spend in their place [The world was trying to increase savings without being willing to increase lendings.] Suddenly, total spending in the world economy plunged, and because my spending is your income and your spending is my income, incomes and employment plunged too.

So can anything be done? That’s where we come to the third lesson from the babysitting co-op: big economic problems can sometimes have simple, easy solutions. The co-op got out of its mess simply by printing up more coupons. …Could we cure the global slump the same way? Would printing more babysitting coupons, aka increasing the money supply, be all that it takes to get Americans back to work? Well, the truth is that printing more babysitting coupons is the way we normally get out of recessions.

For the last fifty years the business of ending recessions has basically been the job of the Federal Reserve, which (loosely speaking) controls the quantity of money circulating in the economy; when the economy turns down, the Fed cranks up the printing presses. And until now this has always worked. It worked spectacularly after the severe recession of 1981–82, which the Fed was able to turn within a few months into a rapid economic recovery… It worked, albeit more slowly and more hesitantly, after the 1990–91 and 2001 recessions.

But it didn’t work this time around. I just said that the Fed “loosely speaking” controls the money supply; what it actually controls is the “monetary base,” the sum of currency in circulation and reserves held by banks. Well, the Fed has tripled the size of the monetary base since 2008; yet the economy remains depressed. So is my argument that we’re suffering from inadequate demand wrong? No, it isn’t.

…So what [happened] to us? We found ourselves in the unhappy condition known as a “liquidity trap.”

The Liquidity Trap

…[When the 2008 recession hit] the Federal Reserve …responded by rapidly increasing the monetary base. Now, the Fed—unlike the board of the babysitting co-op—doesn’t hand out coupons to families; when it wants to increase the money supply, it basically lends the funds to banks, hoping that the banks will lend those funds out in turn. (It usually buys bonds from banks rather than making direct loans, but it’s more or less the same thing.) This sounds very different from what the co-op did, but the difference isn’t actually very big. Remember, the rule of the co-op said that you had to return as many coupons when you left as you received on entering, so those coupons were in a way a loan from [the coop] management.

Increasing the supply of coupons therefore didn’t make [babysitting economy] richer—they still had to do as much babysitting as they received. What it did, instead, was make them more liquid, increasing their ability to spend when they wanted without worrying about running out of funds.

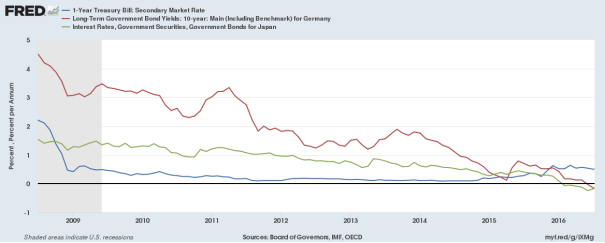

Now, out in the [US economy] people and businesses can always add to their liquidity, but at a price: they can borrow cash, but [they] have to pay interest on borrowed funds. What the Fed can do …is drive down interest rates, which are the price of liquidity—and also, of course, the price of borrowing to finance investment or other spending. So in the [US] economy, the Fed’s ability to drive the economy comes via its ability to move interest rates.

But here’s the thing: it …can’t push them below zero, because when rates get close to zero, just sitting on cash is a better option than lending money to other people. And in the current slump it didn’t take long for the Fed to hit this “zero lower bound”: it started cutting rates in late 2007 and had hit zero by late 2008. Unfortunately, a zero rate turned out not to be low enough… Consumer spending remained weak; [and] business investment was low… And unemployment remained disastrously high.

And that’s the liquidity trap: it’s what happens when zero isn’t low enough, when the Fed has saturated the economy with liquidity to such an extent that there’s no cost to holding more cash, yet overall demand remains too low.

A “liquidity trap” is a weird name for a situation where the Fed is “trapped” because it has driven short-term interest rates to zero and so further monetary stimulus won’t have any effect because interest rates can’t go below zero. Back to Krugman:

Let me go back to the babysitting co-op one last time… Suppose for some reason …most of the co-op’s members decided that they wanted to [hoard coupons and] run a surplus this year, putting in more time minding other people’s children than the amount of babysitting they received in return, so that they could do the reverse next year.

…That’s more or less what …happened to America and the world economy as a whole. When everyone suddenly decided that debt levels were too high, debtors were forced to spend less, but creditors weren’t willing to spend more, and the result [was] a depression—not a Great Depression, but a depression all the same. Yet surely there must be ways to fix this. It can’t make sense for so much of the world’s productive capacity to sit idle, for so many willing workers to be unable to find work. And yes, there are ways out. Before I get there, however, let’s talk briefly about the views of those who don’t believe any of what I’ve just said.

Is It Structural?

I believe this present labor supply of ours is peculiarly unadaptable and untrained. It cannot respond to the opportunities which industry may offer. This implies a situation of great inequality—full employment, much over-time, high wages, and great prosperity for certain favored groups, accompanied by low wages, short time, unemployment, and possibly destitution for others.

—Ewan Clague

The quotation above comes from an article in the Journal of the American Statistical Association. It makes an argument one hears from many quarters these days: that the fundamental problems we have run deeper than a mere lack of demand, that too many of our workers lack the skills the twenty-first-century economy requires, or too many of them are still stuck in the wrong locations or the wrong industry.

But I’ve just played a little trick on you: the article in question was published in 1935. The author was claiming that even if [there was] a great surge in the demand for American workers, unemployment would remain high, because those workers weren’t up to the job. But he was completely wrong: when that surge in demand finally came, thanks to …World War II, all those millions of unemployed workers proved perfectly capable of resuming a productive role. Yet now, as then, there seems to be a strong urge—an urge not restricted to one

side of the political divide—to see our problems as “structural,” not easily resolved through an increase in demand….Sometimes this argument is presented in terms of a general lack of skills. For example, former president Bill Clinton …told the TV show 60 Minutes that unemployment remained high “because people don’t have the job skills for the jobs that are open.” Sometimes it’s framed in terms of a story about how technology is simply making workers unnecessary—which is what President Obama seemed to be saying when he told the Today Show,

There are some structural issues with our economy where a lot of businesses have learned to be much more efficient with fewer workers. You see it when you go to a bank and you use an ATM, you don’t go to a bank teller. Or you see it when you go to the airport and you use a kiosk instead of checking at the gate.

…And most common of all is the assertion that we can’t expect a return to full employment anytime soon, because we need to transfer workers out of an overblown housing sector and retrain them for other jobs. Here’s Charles Plosser, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, and an important voice arguing against policies to expand demand:

You can’t change the carpenter into a nurse easily, and you can’t change the mortgage broker into a computer expert in a manufacturing plant very easily. Eventually that stuff will sort itself out. People will be retrained and they’ll find jobs in other industries. But monetary policy can’t retrain people. Monetary policy can’t fix those problems…

OK, how do we know that all of this is wrong? Part of the answer is that Plosser’s implicit picture of the unemployed—that the typical unemployed worker is someone who was in the construction sector, and hasn’t adapted to the world after the housing bubble—is just wrong. Of the 13 million U.S. workers who were unemployed in October 2011, only 1.1 million (a mere 8 percent) had previously been employed in construction…

Construction workers were only about 5% of the labor force in 2006, so their share of total unemployment was surprisingly small given that the housing bubble precipitated the entire economic crisis. Ninety-two percent of unemployment was in other sectors of the economy where there was no obvious reason why there should be a slowdown.

More broadly, if the problem is that many workers have the wrong skills, or are in the wrong place, those workers with the right skills in the right place should be doing well. They should be experiencing full employment and rising wages. So where are these people?

There were very few sectors of the economy where unemployment was as low during the Great Recession as it was in normal times. The fracking boom in the great plains was about the only place with normal, low unemployment, but the fracking companies were only looking for a few thousand skilled workers whereas the excess unemployed American workers numbered in the tens of millions.

…The bottom line is that if we had mass unemployment because too many workers lacked the Right Stuff, we should be able to find a significant number of workers who do have that stuff prospering—and we can’t. What we see instead is impoverishment all around, which is what happens when the economy suffers from inadequate demand…

the private sector, collectively, is trying to spend less than it earns, and the result is that income has fallen. Yet we’re in a liquidity trap: the Fed can’t persuade the private sector to spend more just by increasing the quantity of money in circulation. What is the solution?

Krugman goes on to argue that when monetary stimulus loses its effectiveness due to a liquidity trap, fiscal stimulus should be used because it is more effective in a liquidity trap when the government can borrow money for negative real interest rates. The massive military of World War II finally ended the Great Depression, so more productive spending on education, infrastructure, military training, and other domestic priorities (rather than just blowing up stuff like in WWII) would work again.

Alternatively, the Fed could get more aggressive in its monetary policy. It could do like the Babysitting coop and print money to loan $1,000 to every American adult at a low interest rate. Or it could do a “helicopter drop” and just give the money to every American. This was one of Milton Friedman’s ideas for how to avoid using a fiscal stimulus when there is a deflationary liquidity trap.

Of course, if the Fed is giving everyone money on behalf of the US government, then is there really much difference between monetary stimulus (the Fed pumping out money) and a fiscal stimulus (the Treasury pumping out money)? They both work the same way. The government could accomplish the same thing via a “fiscal stimulus” by borrowing money at zero percent interest (the going rate in a liquidity trap) and giving $1,000 to every American. Both would have essentially the same effect. Indeed, that is more-or-less part of what Obama’s 2009 fiscal stimulus did when the government borrowed money to give all working Americans a tax cut (or increase tax rebates). About a third of the 2009 fiscal stimulus was for tax cuts.