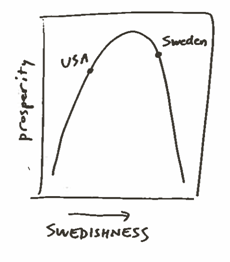

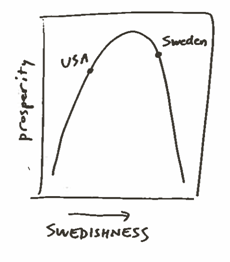

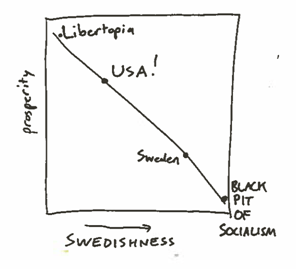

Jordan Ellengerg’s book, How Not To Be Wrong: The Power of Mathematical Thinking has an entire chapter about how surprisingly difficult it is for people to think in terms of non-linear relationships like the equity-efficiency curve. On page 23, he draws a very similar curve that describes how much government intervention is optimal for a nation. At one end of the curve is communism and the other end is anarchy. He humorously calls it the “Swedishness” curve but what he means by that is government intervention or socialism.

In any case, the left side of the curve should end a lot lower than the right side of the curve because all real examples of anarchy certainly have less prosperity than communism. I’m talking about nation-state size populations rather than tribes or villages that are left alone by other people. Anarchy can work fine for a small group of people as long as they can avoid disputes with bigger or more powerful groups of people. There are many examples of both anarchy and communism with varying outcomes, so it is a gross simplification to represent the curve as a precise line, but even the worst example of communism is probably more prosperous than the average example of anarchy. I’m not sure what the worst example of communism is because there are so many examples: North Korea, Cambodia, etc. I’m not sure what the best example of anarchy is either (Somalia in the 1990s, medieval Iceland, etc.) but all examples of large-group anarchy are all either extremely poor, or extremely short lived. Mass-society anarchy in the 20th century has been much less stable than communism. The worst example of communism might even have a better record of creating prosperity than the best example of anarchy! It is hard to know for certain because there is no government to collect statistics about prosperity under anarchy.

However, there is no doubt that the best example of communism was FAR, FAR better at creating prosperity than the best example of anarchy. The Soviet Union was far better at creating prosperity than any other example of communism and it worked quite well for almost half a century. We all tend to think of it as being a basket case now, but that is historical revisionism. It is easy to forget that the communist Soviet Union was one of the two great superpowers of the 20th century.

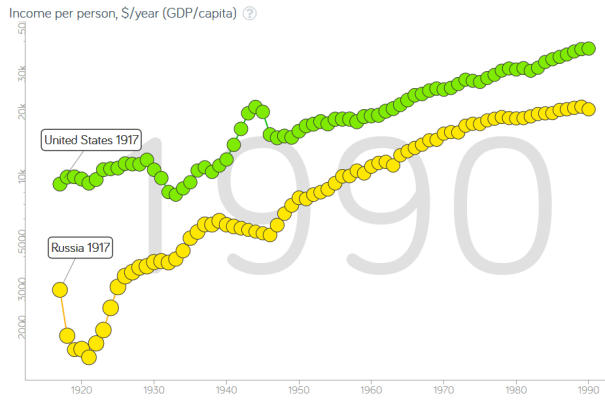

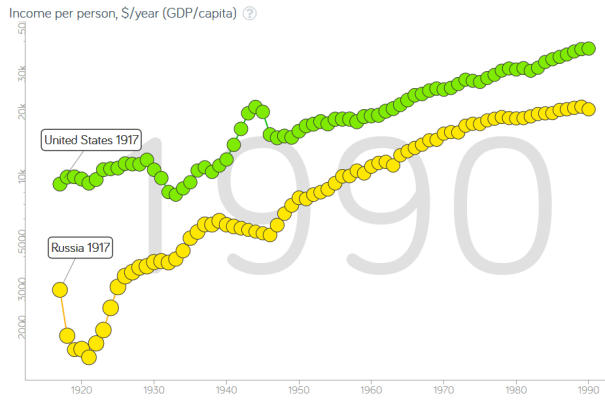

The USSR grew quite rapidly for 40 years after the 1917 communist revolution as you can see in this Gapminder graph comparing Russia and the US.

This graph shows the best measure of economic prosperity that we have, GDP/capita, on the vertical axis. It is in log scale because that represents the relative progress between the two nations as the size of the gap between the two lines. The gap narrowed from 1920 until 1939 because Russian growth was faster than US growth until WWII when Russian GDP was artificially suppressed by wartime destruction whereas US GDP was artificially boosted by government production and the gap widened. WWII was so horrific in Russia that life expectancy dropped to under 16 years which is much worse than conditions on the western front to say nothing of in the US. US life expectancy actually rose during WWII, perhaps in part because massive wartime spending finally helped the economy recover completely from the Great Depression. After WWII the economic gap between the US and Russia dramatically narrowed as life normalized in the later half of the 1940s and Russia again grew faster than the US. Overall, average Russian growth was faster than US growth until sometime in the 1970s when Russian growth stagnated and the slope of the yellow line levels off.

When capitalist progress collapsed during the Great Depression of the 1930s, the USSR economy kept right on chugging along without any problem with unemployment. That made it look appealing to unemployed workers in the US where unemployment reached 25%. Then it turned what had been a 3rd-rate military power under the Tsars into a superpower on par with the USA and bore the majority of the weight of defeating the Nazis in WWII. It detonated a nuclear bomb only four years after seeing the US drop one on Japan and then launched the space race by putting the first satellite into orbit and the first human in space. They were also a superpower in international competitions like chess and the Olympics where the USSR usually won the most medals.

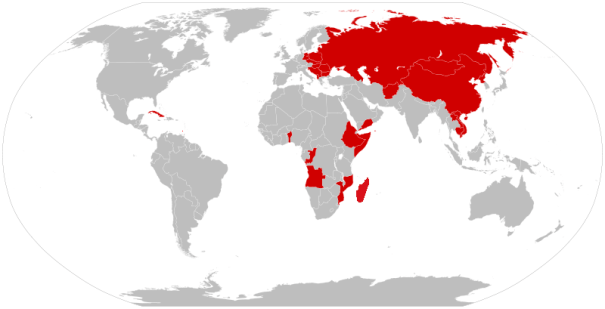

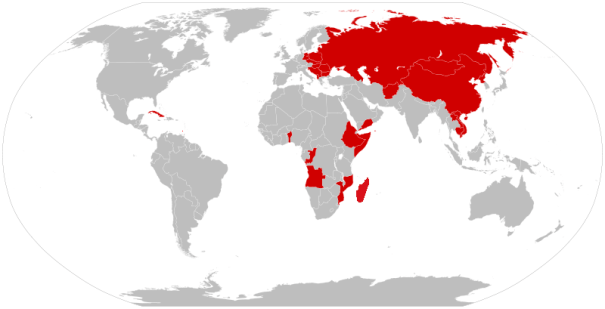

The USSR’s dramatic economic success until the 1970s is what inspired a half century of imitators around the globe. It inspired armed communist insurgencies in about 30 nations around the world. Communism became a particularly attractive model for the former colonies in the “3rd world” whose economies had stagnated in poverty under the capitalist management of the “1st-world” nations of Europe. The USSR was then called the 2nd-world and it had been an economic development miracle in comparison to capitalist colonialism. The fledgling independent governments that the 1st-world nations left in place when they granted independence to their former colonies were largely composed of the same old capitalist elitist that had been so unsuccessful at economic development under colonialism and many of their peoples wanted something different. The fact that many capitalists in the 1st-world were terrified of communism only burnished the appeal of 2nd-world economics in the 3rd world. The map below shows the countries that were officially communist in 1980. Many more nations were run by communists at some other point in history and communist parties have achieved at least partial power many capitalist nations. For example, communists have had some degree of official political power over many European nations to the extent that six European nations have elected representatives of communist parties to the European Parliament.

Oddly, except for the USSR, no other communist nation was particularly successful at growing economic prosperity. China and Vietnam have grown spectacularly since about 1980, and they still claim to be communist, but they achieved economic success by gradually abandoning soviet-style communism and adopting state-directed capitalism in a way that is more like a blend of Singapore and fascist economics than free-market capitalism. Unlike the USSR, their economic success can hardly be ascribed to communism even if they do retain a much larger degree of government ownership and government involvement in business management and planning than in western capitalism.

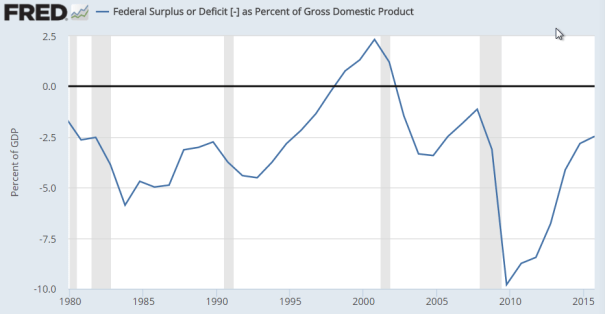

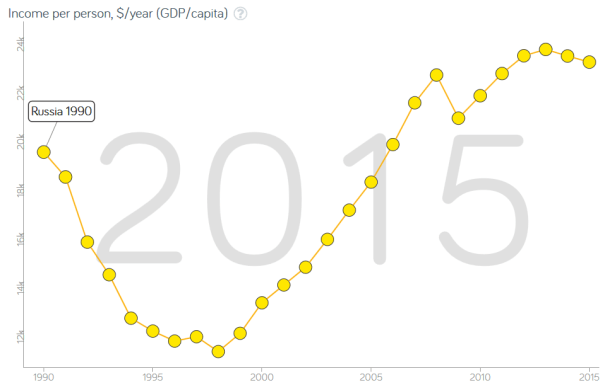

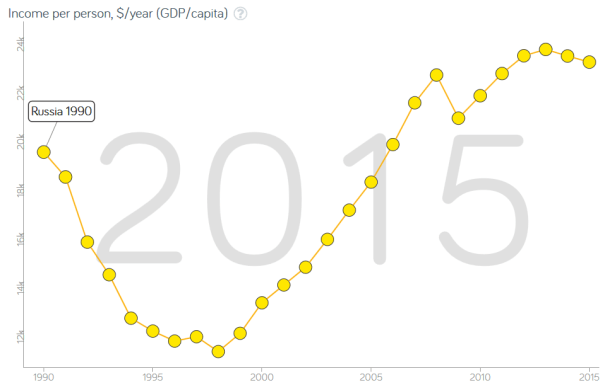

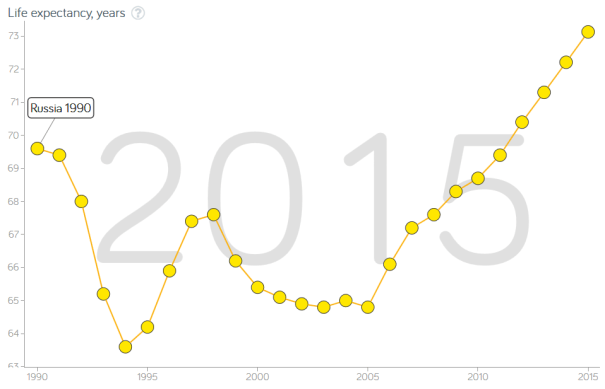

The communist nations of East Asia were not successful economically, but even so, they succeeded militarily in fighting the combined weight of the US and allies to stalemate in Korea and then succeeded in driving the US out of Vietnam. In the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan was convinced that the USSR had surpassed America in military might. Ironically, the USSR’s economy had been stalling at that point and their military was stagnating, but Americans believed Reagan’s fears that the USSR military was ahead of the US and cold war movies like Firefox (1982), The Day After (1983), and Red Dawn (1984) are good illustrations of popular sentiment during the Reagan era. The last big cold-war movie in this genre was The Hunt for Red October which was released in 1990, after the USSR was already disintegrating, but even then Soviet supremacy still felt real enough to make it a blockbuster. To modern eyes, the movie looks like a strange alternate reality because we tend to remember the USSR as a basket case whereas the communists were portrayed in the movie as being terrifyingly super powerful. Although the USSR was already stagnating in the 1980s, the Russian economy did not collapse until the transition to capitalism from 1990 until 1998 as you can see in the Gapminder graph below. Russia didn’t even recover the economic prosperity it had at its peak under communism in 1989 until 2007 and much of that was due to the rise in energy prices bringing it prosperity as one of the world’s biggest oil and gas exporters. Lower oil prices since then (and economic sanctions against its military adventures in Ukraine) have produced another round of economic stagnation since 2008.

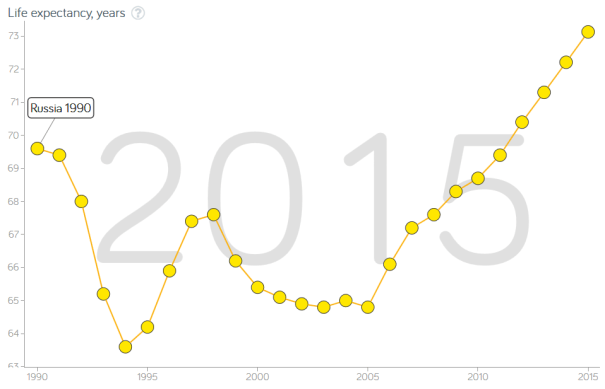

Russian life expectancy also plummeted under capitalism and didn’t recover back to its peak under communism until 2012.

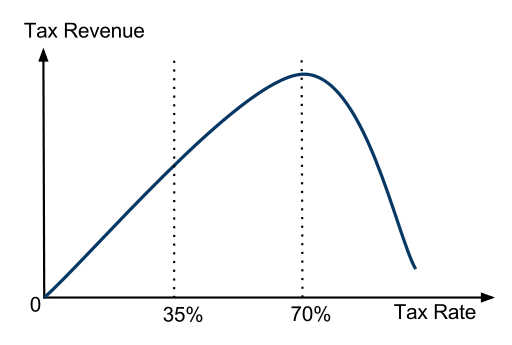

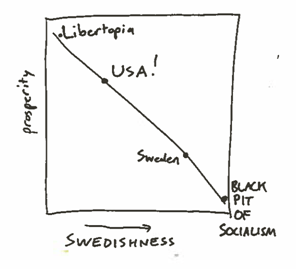

The fact that Russia has done far worse in growing both GDP and life expectancy under capitalism than it did under communism is a good example of the complexities of both kinds of systems. Ellengerg’s book correctly points out that many people today think that there is a linear relationship between capitalism and communism with capitalism being successful at one end of the line and communism being a failure. As the Russian experience demonstrates, this is false. And the opposite of communism is not capitalism, but anarchy. Capitalism is somewhere in the middle between communism and anarchy because capitalism cannot exist without some amount of socialism. Zero socialism is anarchy and capitalism cannot survive for long under anarchy. Capitalism can produce higher prosperity than either communism or anarchy, but multiple different combinations of government and markets can produce similar levels of prosperity from socialist-leaning Sweden and Norway to Singapore to the US. Linear thinkers think the world is like this (in which ‘Swedishness’ is really a measure of socialism again):

Milton Friedman was easily one of the ten most influential economists of the 20th century and he famously said, “I’m in favor of cutting taxes under any circumstances and for any excuse, for any reason, whenever it’s possible.” Friedman was a meticulous, nuanced thinker in his academic work, but in his popular work, he sometimes promoted sloppy thinking as this quote illustrates. He was a libertarian who said here that he would cut taxes to zero. That would not result in libertarian capitalist utopia, but anarchy. Friedman was an ardent believer in capitalism, not anarchy, and he realized that some taxes are inevitable. Even so, it is so easy to fall into the trap of linear thinking that even Friedman fell into it in his quote which is generally parroted by people with much less nuanced thinking.

Although Friedman’s quote exhibits some sloppy linear thinking, he clearly understood the non-linear relationship between socialism and prosperity. He even helped invent payroll tax withholding for the US government as a way to raise tax revenues more efficiently, so he clearly didn’t advocate for zero taxation in all cases! He just thought that the peak prosperity of capitalism could be achieved with a little less socialism than the Swedish voters want. Although many Americans think that Sweden is socialist, they don’t agree. They have never officially called their economic system socialist and in some ways they are more free-market than the US.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7298003/Screen%20Shot%202016-10-18%20at%209.38.48%20AM.png)