For centuries, markets have been expanding into ever greater spheres of human life and displacing non-market human interaction. This has been an exciting time for economists because economists mostly just study markets. This has led economists to neglect major spheres of human activity such as the economic interactions within households and families which is unfortunate because the family has always been a much more important institution for the creation and distribution of goods and services than markets due to the fact that the majority of Americans have always gotten more of their goods and services via households than markets.

Libertarian economists have particularly celebrated the relentless expansion of markets as you can see at the website, Markets In Everything or among anarcho-capitalists like David Friedman who hopes that markets will eventually expand to completely replace government. Recently there have been signs that the forward march of markets may have reversed and markets are now a shrinking share of total economic activity. For example, the FRED graph below shows that the percent of Americans who worked in markets peaked in the year 2000 at a bit under 50%.

We don’t have a measure of non-market economic activity, so we cannot know when the market share of total economic activity peaks, but this graph probably gives the single best measure of how much of Americans’ lives are dominated by markets because labor income is the majority of GDP, Americans households get over 80% of their income from working, and market work is the single biggest time commitment for most adults after sleep. The blue line represents the percent of Americans with any amount of market work and the red line is just the full-time workers. It shows that only about 30-something percent of the American population has ever been working full time. Presumably, most part-time workers rely on sharing resources with family, so the blue line somewhat overstates the importance of markets.

Since 2000, the relative importance of markets has been shrinking as fewer Americans have been working for pay. This trend is compounded by the fact that each worker has been working fewer hours per week for decades as you can see below. The graph shows two different data series that are not perfectly in sync due to measurement error, but both show the same basic story of declining work hours and the same thing is happening in all rich countries around the world. As individuals get wealthier, they tend to spend less time working.

Although the employment-population ration in first graph has been trending back upward again since the last recession, this is probably just a temporary rise that is due to the economic recovery and the next recession will push it back down again. The US labor market is unlikely to ever return to the peak employment level reached in 2000 because the American workforce is getting older and more of the population will drop out of the labor force as more Americans retire. In 2015, 22% of the population was age 65 or older and the number of senior citizens is climbing rapidly.

Plus, the percent of American males who are working (blue line) has been steadily dropping since the 1940s mainly because an increasing percentage of men have been getting their livelihoods from nonmarket sources, most notably from rising market work among women in their households. That had been offset by rising female labor-force participation (red line) until it peaked sometime around the turn of the millennium.

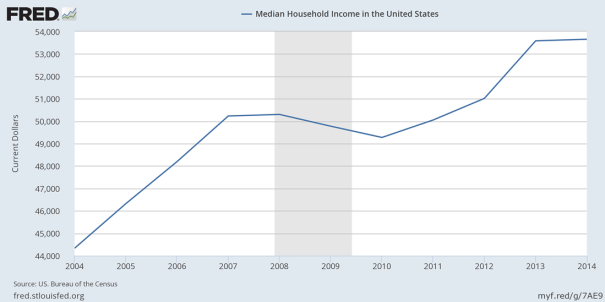

Historically, more Americans have always relied on family for their goods and services than upon market exchange. Our children, students, homemakers, disabled, and/or elderly parents have relied upon gift exchange for their economic wellbeing without market prices attached to the goods and services that they get. That is why the most important economic institution for most Americans has always been the family. But whereas most retired Americans used to live with their families and traditionally got most of their economic resources from their children, retirees are increasingly relying upon government programs for the elderly, notably Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. These government transfer programs have been a steadily rising percent of American market income as the following graph shows. They accounted for over 11% of GDP in 2015 and rising.

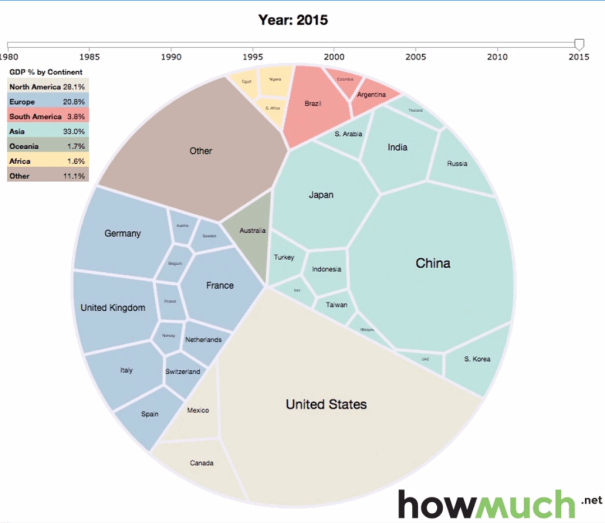

Around the world over the past century, governments have slowly been supplanting markets and increasing the share of GDP that they dominate. The main exception is the formerly communist nations which discovered that it was a bad idea for government to control 100% of GDP. New technology is one reason for the rising dominance of government. Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid would be unthinkably unwieldy without computers and modern communication technology. Information technology has also enabled the rise of mammoth multinational corporations which have come to dominate an increasing share of the global economy. Although corporations interact with suppliers and customers via markets, within corporations, goods and services are produced and distributed according to the dictates of central planners (MBAs) who have proven to be more efficient than markets. There is little difference between how Lockheed Martin manages its 126,000 employees and how Communist Russia’s Uralvagonzavod operates. Although Lockheed Martin is one of America’s biggest private corporations and Uralvagonzavod was founded by communists and continues to be state-run, both get most of their money from government and almost exclusively sell to governments. Communist companies and private corporations operate internally in much the same way. Although corporations and families interact with outsiders via markets, internally they operate more like communism than markets. The expansion of corporations is also a sign that markets are becoming less important. This graph shows World Bank data for the declining share of self-employed Americans.

Small companies are so buffeted by markets that Americans increasingly prefer to work for central planners (MBAs) in big companies. This has been a long-term trend around the world. As nations get richer, their companies tend to get larger and a larger percentage of their workforce becomes employees with steady wages rather than entrepreneurs whose incomes rise and fall with the whims of markets. Usually in poor countries the majority of workers are self-employed entrepreneurs. As nations get richer, fewer people are self-employed and the biggest 2% of America’s firms employ 64% of American workers. Startups are becoming rarer.

Image credit: Inc

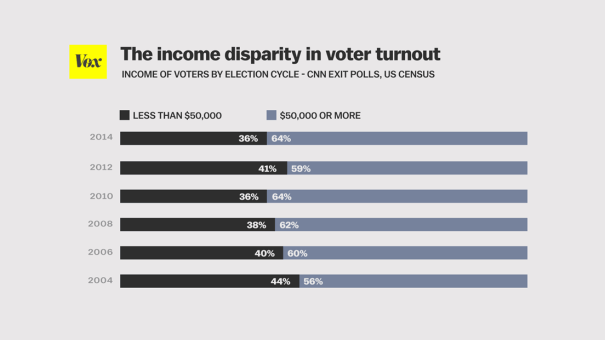

Technological developments contributed to the rise of markets and newer developments are now contributing to their decline. As computers develop smarter artificial intelligence, they will take over more and more jobs thereby either eliminating markets by bringing the price down to zero or by concentrating most of the profits in the hands of a few computer owners. The latter scenario is one where many jobs are being outsourced to computers that benefit a few tech-company owners thereby increasing inequality. Rising inequality will increase the government’s share of the economy because as inequality rises, transfer programs become ever more tempting for democracies because elite wealth becomes more lucrative to tax and the median voter feels more deprived relative to the elites and less sympathetic to letting them live in ever greater luxury. One of the reasons for the rise in government transfer programs like Social Security and Medicare since the 1970s has been the rise in inequality during this time. I expect that technology will continue to increase inequality and that will continue to increase democratic incentives to expand government transfer programs.

But even if there were no increase in government transfer programs, inequality could still destroy markets eventually by eliminating customers. For example, a large rise in inequality would eliminate most of the automobile, housing, and health markets because fewer people could afford these goods and rich elites cannot increase their consumption enough to replace the middle class. Rich elites can only buy a limited quantity of cars, houses, and doctor visits before they get completely satiated. The idea of consumption satiation is so far from most people’s reality that it is hard to imagine and some people think that it is impossible.

Technology is also directly destroying markets. For example, more and more of our information and entertainment is being created by volunteers because technology has made it virtually free for people to collaborate and distribute their creations. Wikipedia wiped out global encyclopedia markets. Open source software has wiped out big swaths of software markets, Craigslist and bloggers have destroyed a large segment of traditional journalism, and music corporations can no longer charge as much for recorded music. Many economists complain that GDP fails to measure the real growth of production in in the digital age because markets are being destroyed as the prices of many information goods are falling to zero and more digital production is moving back to the unpaid household sector. GDP fails to measure the fact that consumers are getting more benefit than ever before from greater access to information, music, and video because they aren’t paying for as much of it anymore. If artificial intelligence doesn’t destroy markets by increasing inequality, it will destroy markets by lowering the price of many services so close to zero that they will be given away for free. That is the optimistic scenario in which the median prosperity increases and paid work hours continue to decline. As we reduce our paid work hours, we will spend more time in the gift economy creating digital information and art to donate to the global community and more time creating traditional goods and services like labor-intensive artisanal wooden furniture and epicurean meals to donate to family members and friends.

We will always have markets, but peak market has passed and the economy of the future will be increasingly dominated by gift exchange, corporate management, and government exchange. Get used to it.

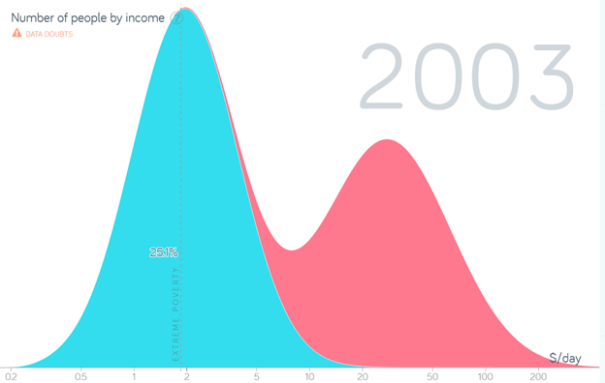

If these two neighbors merged across the Red Sea into one nation the result would look a bit like South Africa. Because the two economies would not be fully integrated, a binomial distribution would be the result as displayed in the

If these two neighbors merged across the Red Sea into one nation the result would look a bit like South Africa. Because the two economies would not be fully integrated, a binomial distribution would be the result as displayed in the