Updated 2/19/23

The first wave of globalization happened due to technological advances in transportation and communication that dramatically reduced transactions costs in the 1800s: Railroads, steel-hulled ships, the screw propeller, telegraph, etc. Then politicians raised tariffs, restricted immigration, and went to war which caused trade and communication to collapse in the early 1900s. The second wave of globalization happened mainly because of lower political barriers (like tariffs), lower communications (fiber optic cables and satellites), and lower transportation costs (due to better aviation and especially the shipping container).

The first big advance in containerized shipping was the invention of the pallet. Skids that resemble pallets date back to Ancient Egypt, but they were little more than sleds and the real advance came first with the use of cranes for loading palletize goods onto ships and especially the development of the forklift starting in the 1800s for moving and stacking pallets inside of warehouses.

“According to an article in a 1931 railway trade magazine, three days were required to unload a boxcar containing 13,000 cases of unpalletized canned goods. When the same amount of goods was loaded into the boxcar on pallets or skids, the identical task took only four hours.”

Containerized shipping was the next big advance and it probably gave a bigger boost to globalization since 1950 than any other technology as detailed by the first history of “The Box” by Marc Levinson.

Consider in how a typical cargo ship would operate before the shipping container. Tim Harford told about a typical 1954 cargo ship, the SS Warrior, that sailed from New York to Germany carrying 5,000 tons of food, vehicles, letters, and other cargo. In total there were 194,582 separate items which required an incredible challenge to track as they were moved around the dock warehouses, loaded onto the Warrior and then the entire laborious process was reversed in Germany. The warehouse workers would pile those 194,582 items onto pallets which were jumbled in the warehouse alongside numerous other pallets that were destined to other ships. The ship took as much time to load and unload as it took to sail across the Atlantic Ocean. Plus, there were even bigger delays in the ports to move the goods into warehouses and then sort out which goods should go onto what trucks and then onto trains and back again, so this laborious process repeated over and over resulting in much longer time loading, unloading, and sorting than the amount of time actually spent transporting.

Although the pallets made it easier to move the goods, they were vulnerable to spoilage from theft, rats, and during the slow loading and unloading process, the goods could be spoiled by rain while exposed on the docks and the decks of ships. Inside the ships, each pallet was a slightly different size and the longshoremen often could not stack them and had to carefully wedge them together between the curved hulls of the ship using hooks and pry bars to try to prevent them all from shifting and spilling over on a rough voyage across the high seas.

The dangers of pallets falling over was severe even in port and this was a severe risk for longshoremen which was a far more dangerous job than manufacturing or construction. Harford says that longshoremen were killed every few weeks in large ports. In 1950, the New York port averaged about 6 serious incidents every day and it was a relatively safe place to work.

The Economist magazine explains containerization:

[C]ontainers—uniform boxes that can be easily moved between lorry, train and ship—have reshaped global trade over the past few decades. Why…?

Uniform metal containers were invented by Malcom McLean …in 1956. Before then goods were shipped as they had been for centuries. Crammed in to the hold of a ship, loose cargo in wooden crates would be loaded and unloaded by vast crews of dockworkers. The process was unwieldy, unreliable and so slow that ships often spent longer docked than they did at sea. Theft of transported goods was rampant: as an old joke put it, dock workers used to earn “$20 a day and all the Scotch you could carry home.”

Containers changed this in several ways. The price of everything fell…

- The cost of loading and unloading fell …to $0.16 per tonne to load compared with $5.83 per tonne for loose cargo. …

- Because containers were packed and sealed at the factory, losses to theft plummeted, which in turn drastically reduced insurance costs.

- More could also be loaded: in 1965 dock labour could move only 1.7 tonnes per hour onto a cargo ship; five years later they could load 30 tonnes in an hour.

- As a consequence, ships could get bigger and more efficient while still spending less time in port.

- As containers made inland distribution by train and lorry easier, ports became bigger and fewer in number. (In 1965 there were 11 loading ports in Europe; by 1970 there were three.) This, along with increased productivity, meant fewer dockworkers were needed.

Furthermore, the Box eliminated the need for warehouses at every port and trainyard. The box itself is a mobile warehouse which is rainproof, ratproof and relatively theftproof.

The Economist article also claimed that the Box undermined the bargaining power of longshoremen unions which is completely false. The longshoremen unions have achieved incredible wages due to containerization. Harold Meyerson says that they are “this country’s best-paid blue-collar workers; many make more than $100,000 a year.” Although there are only a tenth as many people working the docks as in 1950, their wages are incredible because they are so much more productive and an upset longshoreman can sabotage an incredibly expensive process if he is not happy. That gives enormous bargaining power.

Because containers ships are can be loaded and unloaded about 97% faster, and make it easy to stack much higher, they have enabled ships to grow in size so that modern container ships are over 20 times larger than the typical ship of the 1950s, and larger ships are more fuel efficient and labor efficient. The biggest container ships are now as big as the Empire State Building and they are so big that they would require a train that is 90 miles long to carry all 24,000 of their 20ft containers.

New research also claims that containerization is the most important reason that trade has increased over the past half century.

[The authors] find that containerisation is associated with a 320% increase in bilateral trade over the first five years and 790% over 20 years. A bilateral free-trade agreement, by contrast, boosts trade by 45% over 20 years, and membership of GATT raises it by 285%. In other words, containers have boosted globalisation more than all trade agreements in the past 50 years put together. Not bad for a simple box.

But the effect of containerization was not mainly by reducing the cost of shipping. The improved speed and reliability was just as important in boosting trade by allowing companies to reinvent their supply chains.

Speed and reliability of shipping enabled just-in-time production, which in turn allowed firms to grow leaner and more responsive to markets as even distant suppliers could now provide wares quickly and on schedule. International supply chains also grew more intricate and inclusive. This helped accelerate industrialization in emerging economies such as China, according to Richard Baldwin, an economist at the Graduate Institute of Geneva. Trade links enabled developing economies simply to join existing supply chains rather than build an entire industry from the ground up. But for those connections, the Chinese miracle might have been much less miraculous.

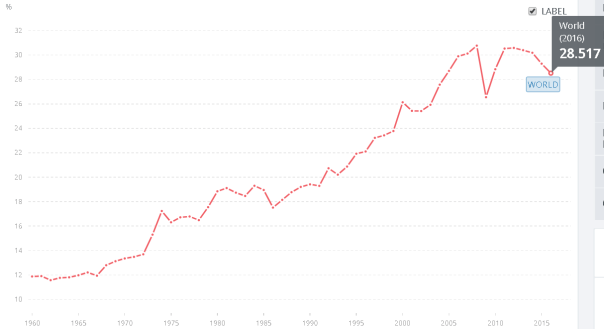

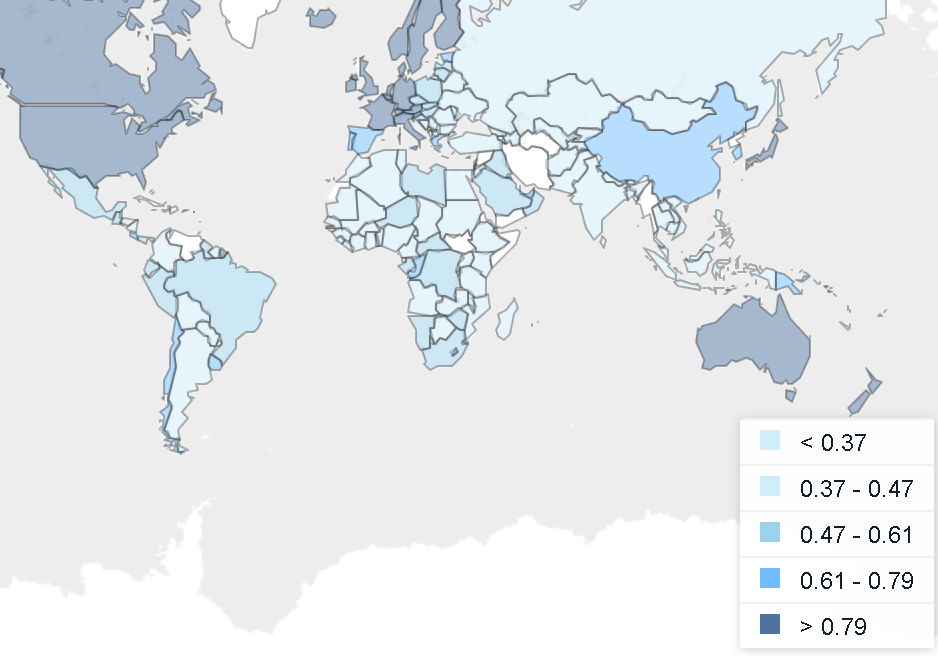

Although globalization seems like it might continue growing forever, it seems to have run out of steam. Here is a measure of globalization according to the latest World Bank data. It is the ratio of exports of goods and services as a percent of world GDP.

This shows that the world is less globalized in the latest data than it was back in 2005! Is rising globalization over? Paul Krugman thinks so:

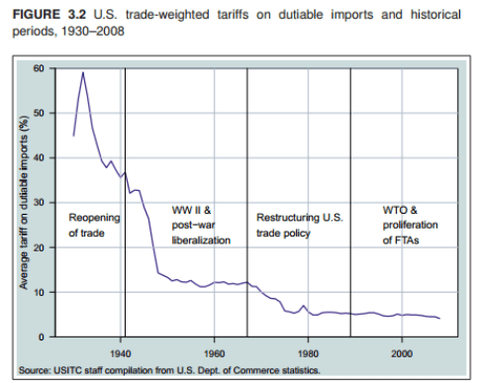

To explain a rising long-term ratio of trade to GDP, we have to turn instead to structural changes in the world economy, of which the most obvious involve declining costs of trade. My view is that rapid trade growth since World War II was driven by two great waves of trade liberalization and one major technological innovation. The first wave of trade liberalization involved industrial countries, and was largely over by 1980:

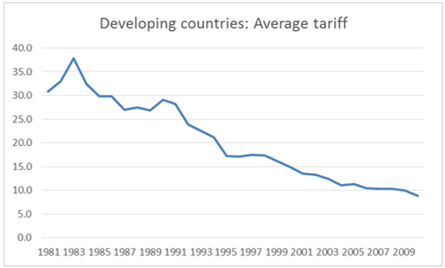

The second wave involved the great opening of developing countries:

This is still going on, but the major opening of Latin America, China, and India is already well behind us. …The point is that it’s entirely reasonable to believe that the big factors driving globalization were one-time changes that are receding in the rear-view mirror, so that we should expect the share of trade in GDP to plateau — and that this doesn’t represent any kind of problem. In fact, it’s conceivable that things like rising fuel costs and automation (which makes labor costs less central) will lead to some “reshoring” of manufacturing to advanced countries, and a corresponding decline in the trade share. Ever-growing trade relative to GDP isn’t a natural law, it’s just something that happened to result from the policies and technologies of the past few generations. We should be neither amazed nor disturbed if it stops happening.

The main technological improvements in shipping and telecommunications have long since run into diminishing marginal returns. International telecommunication is already so cheap that it can’t get much cheaper and the biggest innovation of the past half century in transportation was containerization (i.e. the “box”) which is already over half-century old and there haven’t been much additional gains.

Jessie Romero of the Richmond Fed says that as developing nations catch up technologically and as their wages rise, this could also depress trade:

there are signs of longer-term changes in the Chinese economy. “Two dimensions of the Chinese economy have changed,” says the University of Houston’s Kei-Mu Yi. “First, as they’ve become more technologically proficient, they can make a lot of the intermediate inputs themselves, and to the extent they do, their demand for imports would fall. Second, as their economy has gotten bigger, they are selling more domestically rather than exporting.” Just as China’s entry into the global market boosted trade for the world as a whole, a persistent decrease in China’s trade could depress global trade growth…

In addition, rising labor costs in developing countries could alter the calculation; hourly manufacturing wages in China, for example, have increased on average 12 percent per year since 2001. Natural disasters such as the Fukushima earthquake also could make managers nervous about having long supply chains. Anecdotally, a number of American companies have been “reshoring” manufacturing to the United States. The Reshoring Initiative, an advocacy group, estimates that about 248,000 jobs that left the United States have returned since 2010…

In addition, rising labor costs in developing countries could alter the calculation; hourly manufacturing wages in China, for example, have increased on average 12 percent per year since 2001. Natural disasters such as the Fukushima earthquake also could make managers nervous about having long supply chains. Anecdotally, a number of American companies have been “reshoring” manufacturing to the United States. The Reshoring Initiative, an advocacy group, estimates that about 248,000 jobs that left the United States have returned since 2010.In addition, rising labor costs in developing countries could alter the calculation; hourly manufacturing wages in China, for example, have increased on average 12 percent per year since 2001. Natural disasters such as the Fukushima earthquake also could make managers nervous about having long supply chains. Anecdotally, a number of American companies have been “reshoring” manufacturing to the United States. The Reshoring Initiative, an advocacy group, estimates that about 248,000 jobs that left the United States have returned since 2010…

Constantinescu and her co-authors pinpointed 2000 as the beginning of the decline in the trade elasticity, other research has found that the decline did not occur until the Great Trade Collapse [of 2008].

It is true that trade has collapsed more in places like China and India than in the US. Here is the same data as in the first graph above, but with India, China, and the US added which shows that whereas trade in the US has changed at about the same rate as the rest of the world, trade in India and China has collapsed from where it was a few years ago.

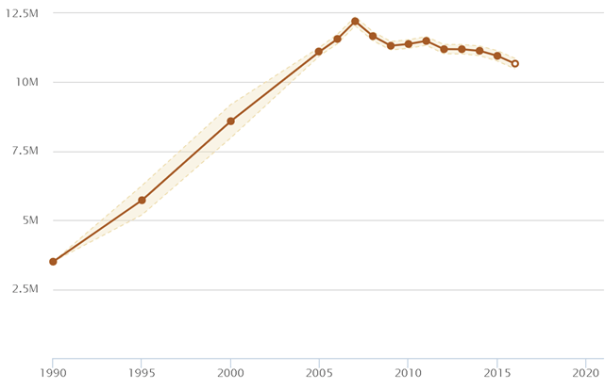

At about the same time as international trade has started falling, immigration also fallen. Immigration to the US peaked over a decade ago in 2007. Here is Pew’s data for the total number of unauthorized immigrants in the US.

Immigration has been declining for a decade too.

(

(