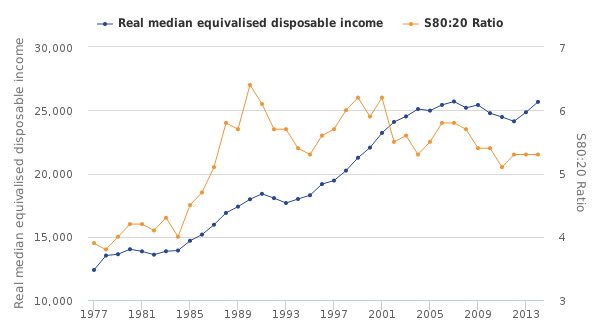

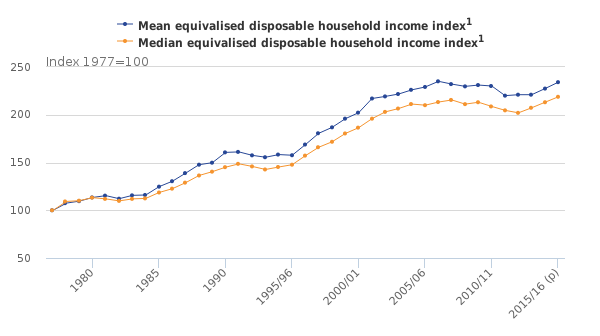

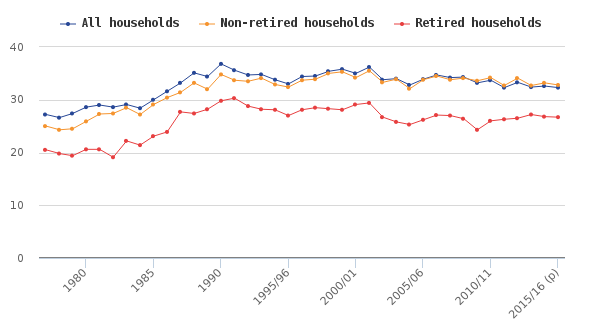

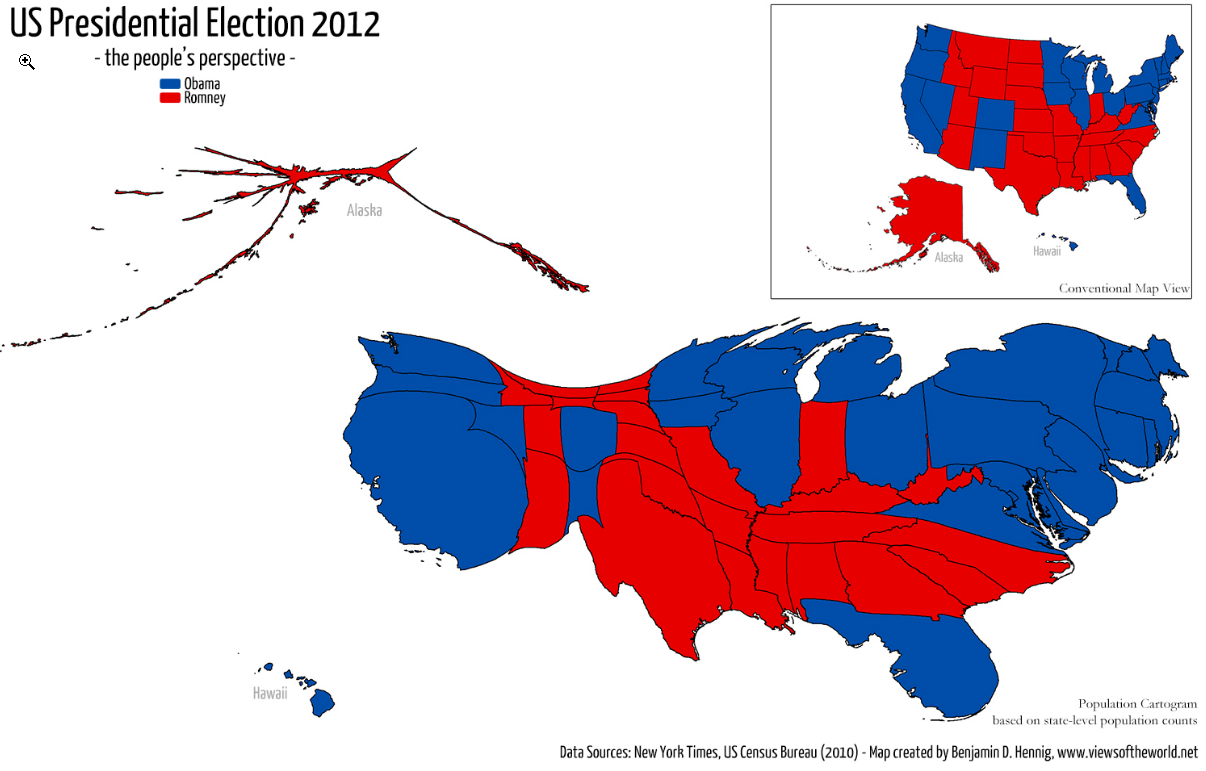

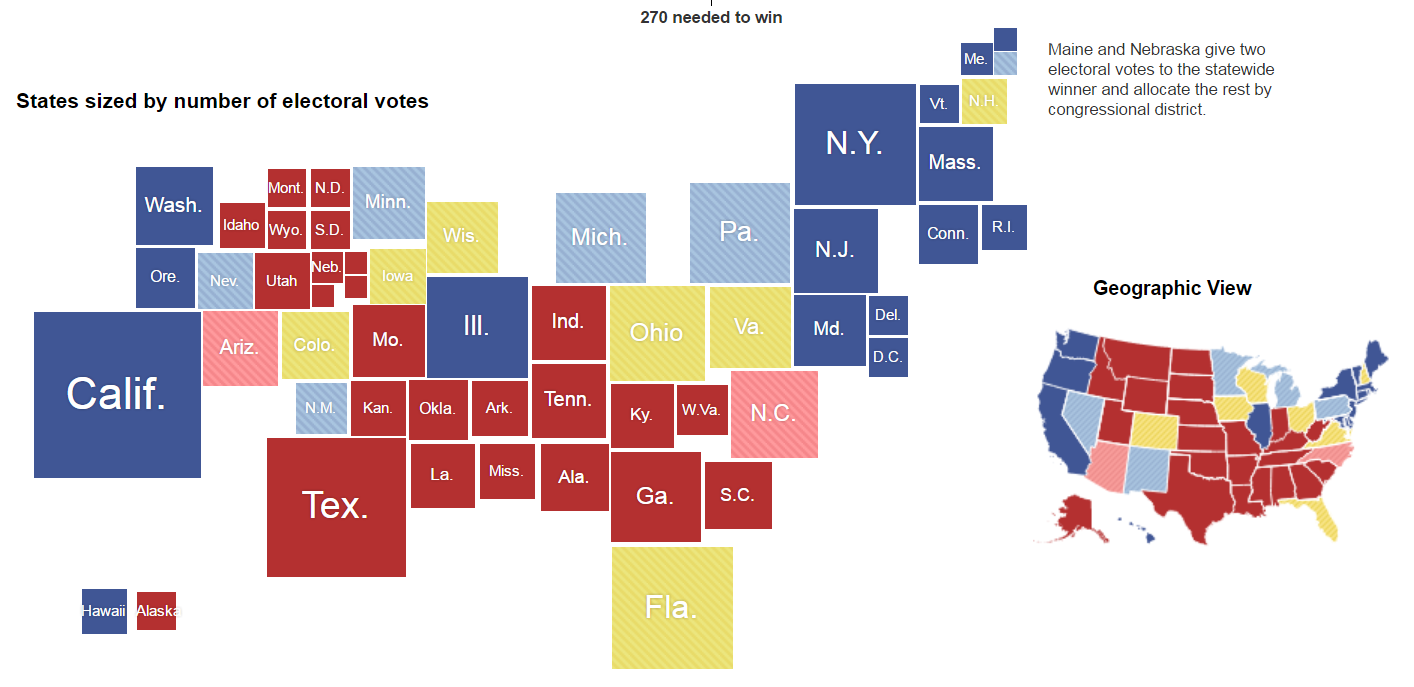

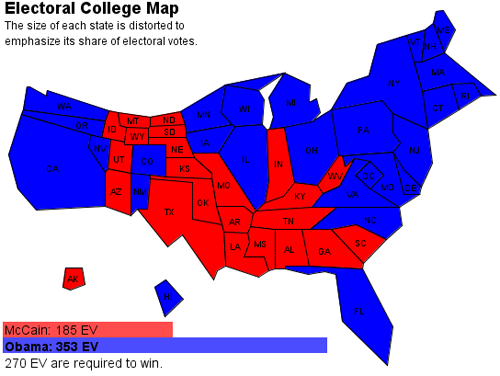

The main point of medianism is that economic measures should prioritize people more than money. That is why median income is a better measure than mean income. Similarly, when we display data about the distribution of economic wellbeing or democratic preferences on maps, they should be adjusted by making population-equalizing cartograms like this map showing the 2012 presidential election in which the area of each state is drawn proportional to its population.

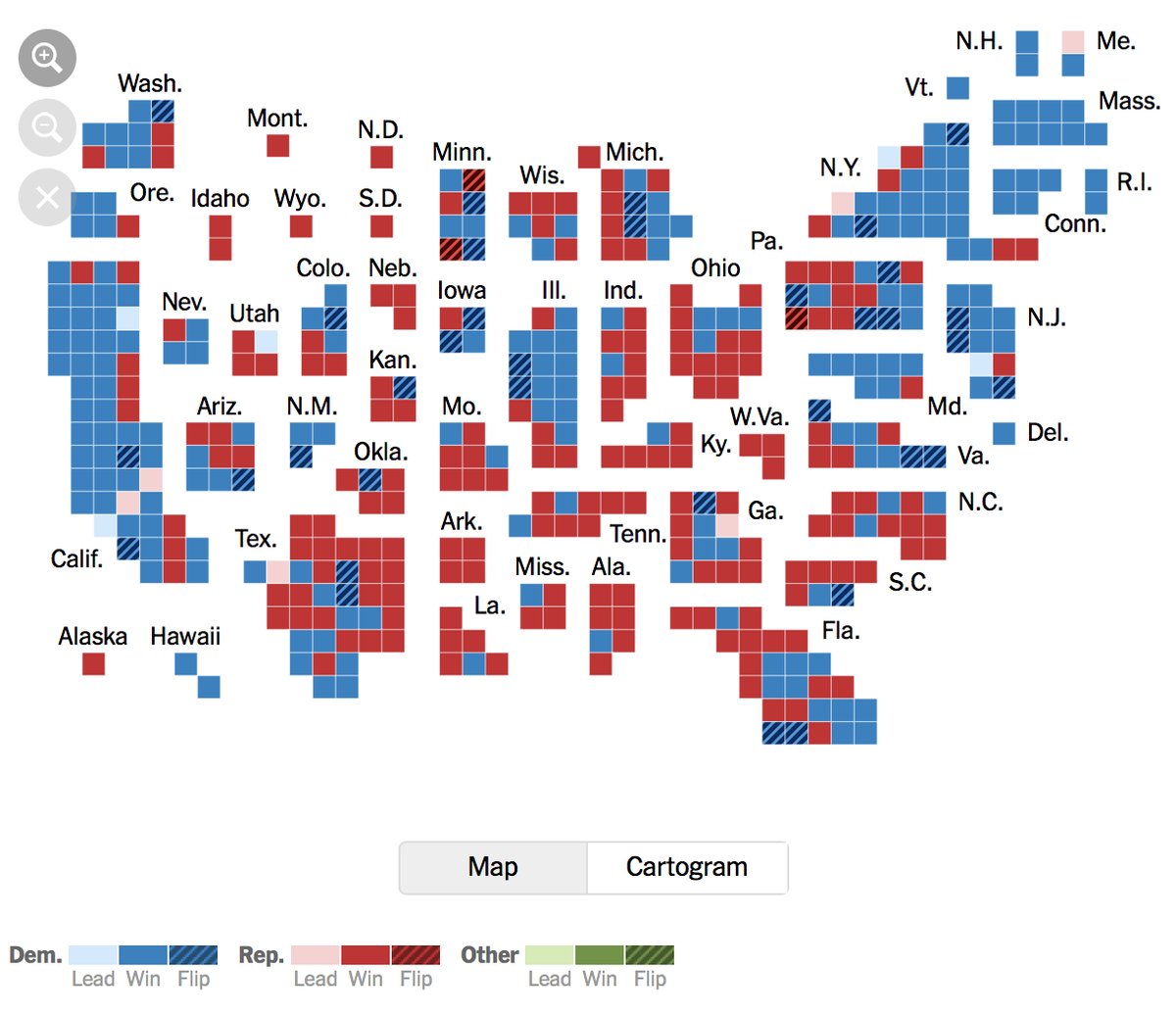

It looks crazy distorted, but you should get used this kind of map because it is a better way to graphically display the political preferences of America. The traditional political map in the upper right corner makes America look a lot redder than it actually was. The New York Times produced another alternative below that has the advantage of making the population of each state more comparable by displaying each state as a square. That makes it clearer that Ohio is bigger than Virginia and Hawaii is bigger than Alaska, but I prefer the cartography above because it is more elegant, it doesn’t require state labels because their shapes are easily recognizable, and it shows the geographic distribution of the voters more accurately which is usually the main point of a map. West Virginia isn’t really located south of Virginia and adjacent to Georgia like in the NYT map below.

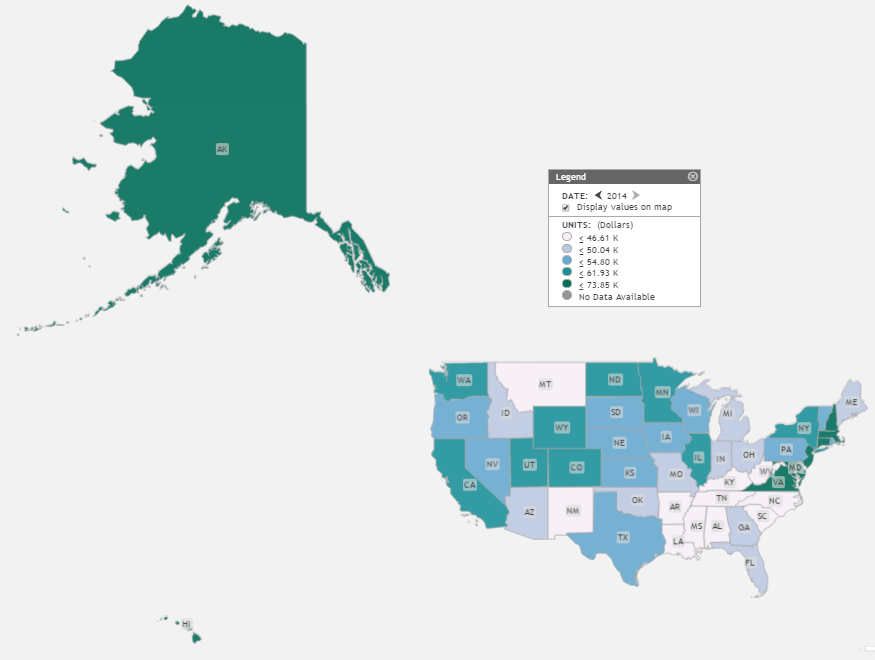

Making area proportional to population would also be a better way to show the distribution of economic variables like median income that mainly impact people rather than acres of land. The Saint Louis Federal Reserve has an excellent tool for mapping economic data called GEOFRED which should be displayed according to population rather than according to geographic area. People think of their map as being realistic, but all maps are distorted simplifications. The point of mapping is to select simplifications that communicate the most useful information. For example, the True Size Of website illustrates how any flat map is distorted because it is a projection of a curved surface. The standard maps that we usually see arbitrarily inflate the size of Alaska and shrink the size of Hawaii relative to the mainland US. Below is an example of the standard mapping projection used by the Saint Louis Fed which displays Alaska and Hawaii alongside the mainland with such distorted areas that they should look ridiculous, but it probably doesn’t because most people are used to it.

On the Fed’s map, Alaska looks bigger than half of the mainland USA when in reality, as the map below shows, Alaska is only about double the area of Texas.

But even this greatly overstates the size of Alaska in terms of human welfare. By population, Texas is over 37 times larger than Alaska, so a map showing human dimensions should show Texas as being 37 times bigger to reflect its human importance.

The population of the US is distributed very unevenly within states as well. About half the population of Illinois is in in the county where Chicago is located and over half the population of New York state is in its southern corner where the New York City metropolitan area is located. Because congressional areas are divided up to have fairly equal population, some congressional districts encompass enormous states like Montana and Alaska whereas the smallest districts would fit in a square that is less than four miles long. When the size of congressional districts is adjusted for population, they should all be approximately the same size because they should ideally have approximately the same population as you can see in this fascinating cartogram by Benjamin Hennig.

The large map on the bottom is a much more accurate representation of the distribution of political strength than the comparable geographic map seen to its upper right. You probably think it doesn’t even look like the USA, but that is only because it is brand new and you aren’t used to looking at it. If more people created this kind of map, we would get used to it and we could also figure out better ways to draw them. For example, it would be easy to make the shape of Alaska look more like Alaska and less like a spider. That would make it evident that Alaska is only about half the size of Hawaii in population. On this map, Alaska is so stretched out, it artificially looks much larger than Hawaii. This map is particularly bizarre because it shows congressional districts which are often stretched into bizarre shapes due to gerrymandering and nobody recognizes their bizarre shapes. They create arbitrary divisions that act a bit like camouflage on the map for people who aren’t familiar with them. When they are erased, and only the population density is displayed, then the cities where most Americans live naturally pop out of the map.

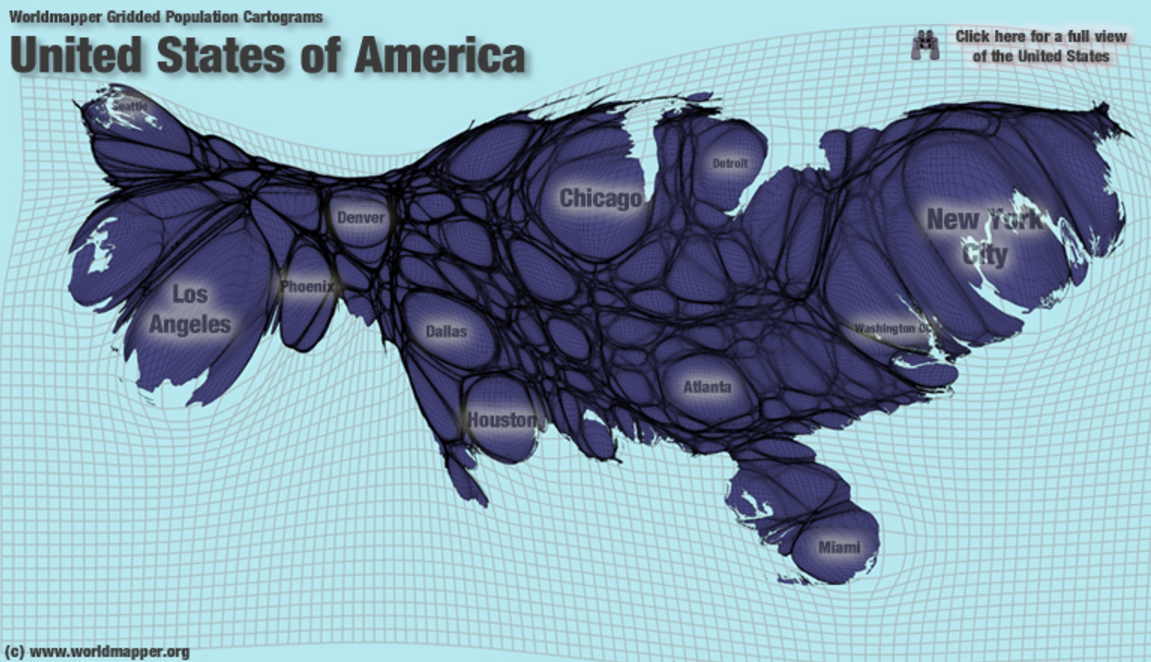

Worldmapper.org has created hundreds of wonderful cartograms for the globe and the following USA cartogram is more intuitive and less messy than the red and blue one above because it eliminates the gerrymandered congressional districts and instead shows lightly-populated rural areas as shrunken dark lines in between lighter-colored cities.

Although this kind of map takes getting used to, it soon becomes easy to identify major metropolitan regions even when they are unlabeled. This map gives insight into our economics that regular maps cannot. For example, it is easier to see the distance between metropolitan areas on this map by the amount of darkness between them. You can see the relative size of the conurbations of the Boston-DC megapolis and which are the closest together.

Toledo is the city just south of Detroit and then there are two bigger metropolitan areas directly south (and a bit west) of Toledo that are so close together, they look like twin cities with only a faint rural membrane separating them. They are Dayton and Cincinnati on the north and south respectively. Whereas the city of Dayton officially has less than half of the population of Toledo, this map accurately shows that its metropolitan area is much bigger than Toledo’s metropolitan area because Dayton has bigger suburbs. That helps explain why the Dayton airport is MUCH bigger than the Toledo airport. It would be interesting to see the locations of major airports superimposed on this map. Then you could see that the Dayton airport is inflated by the fact that it has little competition from the Cincinnati airport which is located in the rural southern edge of the metropolitan area and the Toledo airport is shrunken by competition from the Detroit airport which is nearby in the rural border between these two metropolitan areas.

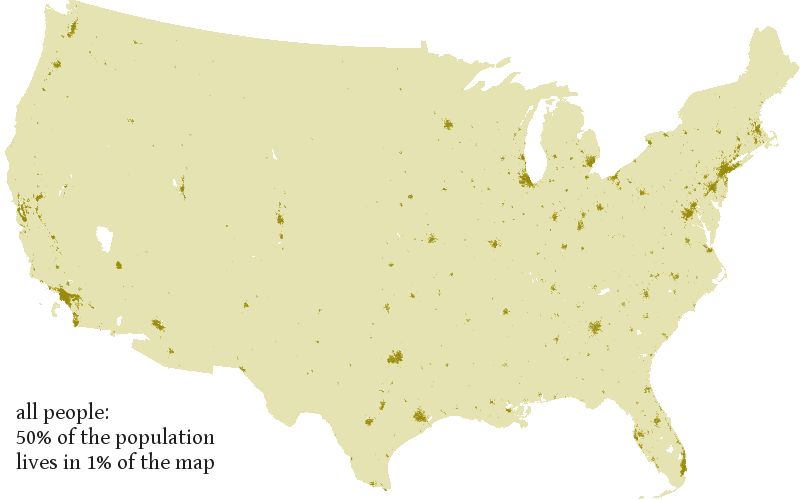

About 2/3 of Americans live in only 4% of our land area and 50% of Americans live on 1% of our land as you can see in this map by Joshua Tauberer, who wrote an excellent article in favor of cartograms. The dark dots on the map below should account for 50% of the area on any map that is trying to represent human geography rather than empty acres of land. That is what the cartograms above do.

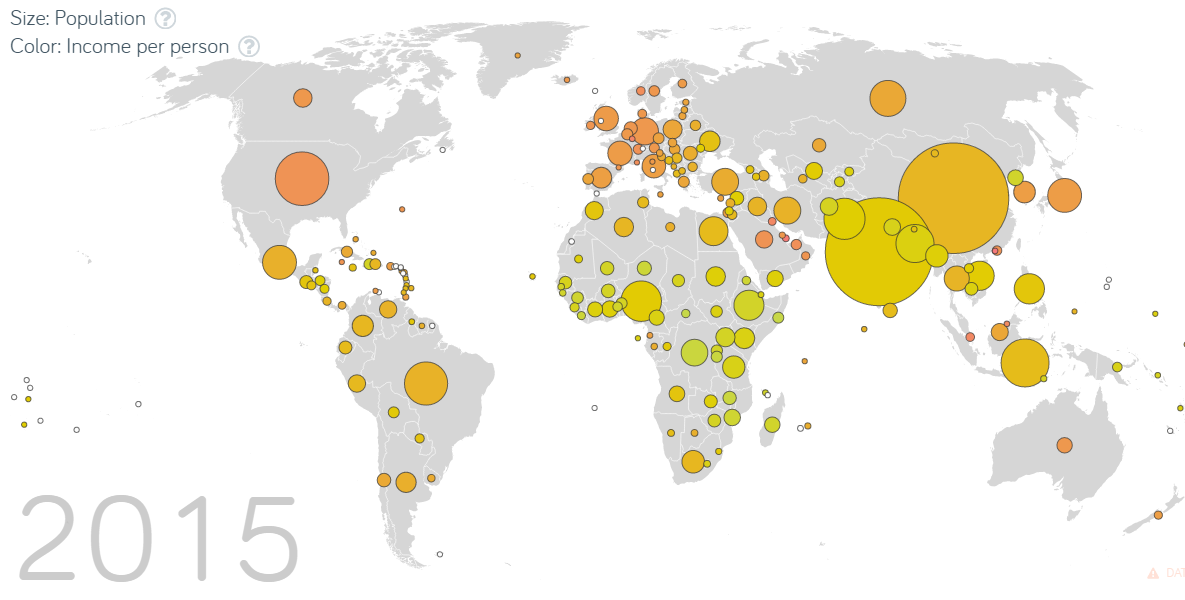

Gapminder also prioritizes human populations on all of its default graphs and maps. Below is a Gapminder world map of income, denoted by the color spectrum, and the population of each nation denoted using areas of circles rather than stretching the areas like in the above cartograms. This works fairly well for comparing the relative populations of spread-out countries like Mexico, Canada, and the US, but it fails for the region around China and India where those two giant circles blot out the map.

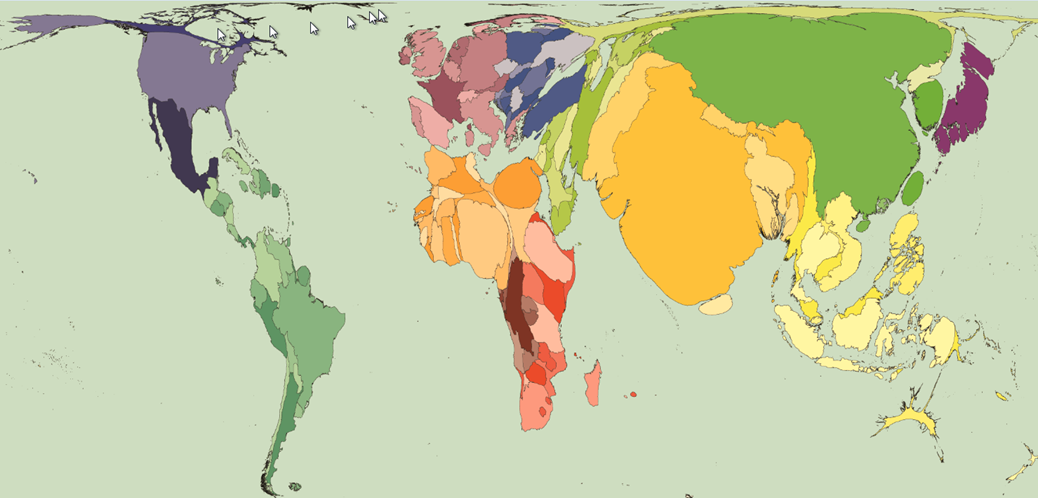

I think worldmapper’s map is a more elegant and realistic way to show the population distribution, but unlike in the Gapminder map, this time the colors are arbitrary.

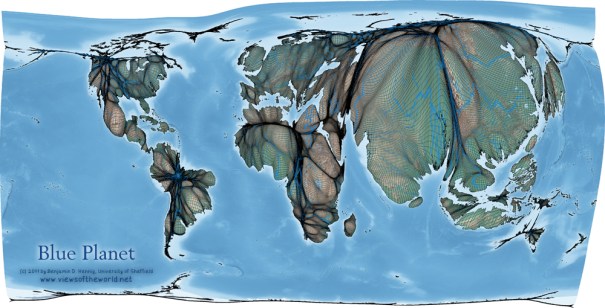

This map could still use work to make it more useful. For example, compare its representation of the US population distribution to the more accurate map above of just the US population that Worldmapper produced. Alaska hardly has any people in it, but it is ridiculously inflated in this Worldmapper map of the world, and the eastern US should be a lot bigger than the Great Plains and intermountain west. Benjamin Hennig has also created another version that more accurately shows population distribution within nations too. The one below shows how rivers run through the peoples of the world, and I also posted an even more beautiful version showing elevations on another post.

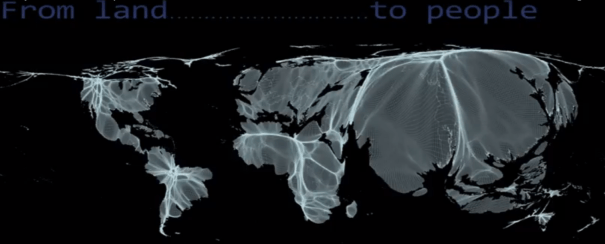

Benjamin Hennig also made a YouTube animation showing a map transforming from prioritizing the distribution of land to the distribution of people. Here is a still from the video:

Soo Oh wrote a “case against cartograms” like these and she has a lot of professional credibility as Vox’s map builder, but it is a very weak case. She made has two basic points: 1. Cartograms are new and unfamiliar which makes it harder to find a geographic region like Iowa on them, and 2. People are bad at making cardinal comparisons between different areas, so area doesn’t matter much.

Her first complaint was aimed at the blocky New York Times cartogram displayed above, but it doesn’t seem like a significant difficulty to me. The NYT solved the problem by simply labelling each square. It doesn’t apply to the Gapminder map above nor to the first cartogram in this essay which roughly maintained the shapes of each state so that they are quite recognizable despite their unfamiliar sizes (except perhaps Alaska which is still identifiable due to its location). This kind of cartogram could be made even more recognizable with a little tweaking of some states’ shapes, particularly Alaska as mentioned above. Furthermore, it is only unfamiliar because nobody uses it. If cartographers like Soo Oh would use it more often, she would demolish hew own complaint because it would soon become easy to find Iowa on the map.

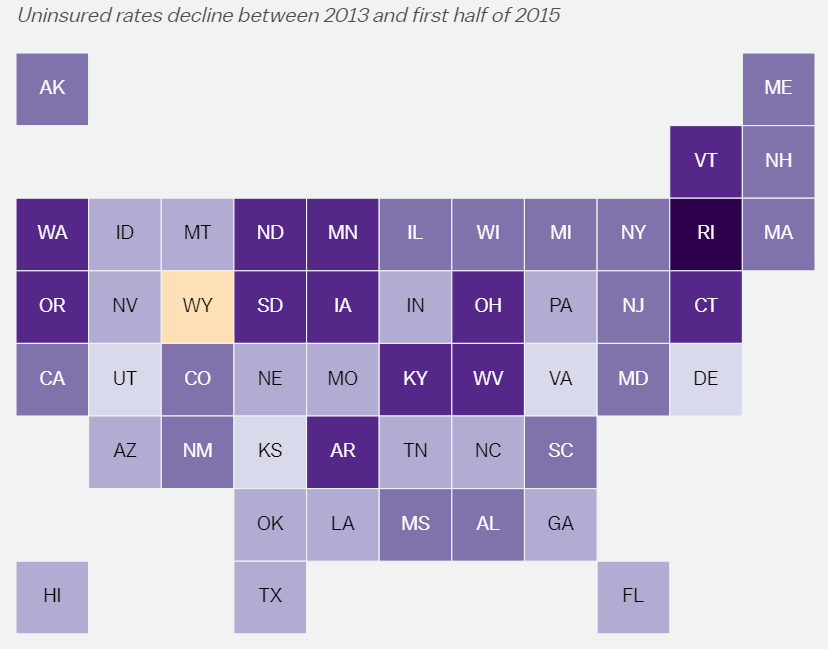

Soo Oh made the second complaint in two different formulations. It is true that people are poor at perceiving the cardinal magnitude of different areas, but we are pretty good at perceiving the ordinal magnitude, so we can still benefit from cartograms with areas that have meaning. For example, It is easy to look at the Gapminder map and see the ordinal differences in size: China’s population circle is bigger than the US which is bigger than Canada’s. It is hard to see accurate cardinal comparisons which would reveal that China is about 4 times larger than the US which is about ten times larger than Canada. Nevertheless, when we care about people more than acres of land, which is true for any map related to the geographic distribution of votes or economic wellbeing, then population-equalizing cartograms are much more accurate than regular maps. Ironically, in Soo Oh’s case against cartograms, she links to an example of the kind of cartogram that she makes, and her own cartogram is worse by her own standards than the ones that she complains about. It is so distorted that it is even harder to find Iowa and other particular states than in any of the cartograms on this page and because each state is exactly the same size, the areas are even more distorted and less useful than in the cartograms she criticizes or traditional maps. There are many tradeoffs in cartography between what kinds of information to prioritize. I advocate for prioritizing the geography of human populations over the geography of empty acres when we are mapping economic welfare or democratic representation. Here she mapped a change in economic welfare and eliminated useful geographic information without adding anything at all.

This preserves the worst of both cartograms and traditional maps. It would be much more useful to display the geographic distribution of the welfare of uninsured Americans if she had just color-coded the map at the beginning of this essay that Benjamin Hennig created for the 2012 election. It isn’t perfect, but it is the best population-weighed cartogram of US states and it should be the standard upon which we should try to build new and improved cartograms.

Here is another example of a population-area map by Sam Wang, who does excellent polling work using the median poll:

It is more blocky than the Woldmapper maps which makes it easier to see relative sizes of the states. For example, it clearly shows that Hawaii is larger than Alaska. But it isn’t as blocky as the NYT map, so you can still identify the states by just looking at their shapes. I think there is more work to be done to create the best tradeoff between stylized blocks (or circles like Gapminder’s map) and stretched geograpic shapes like Worldmapper, but this is better than the standard projection that Sam Wang usually uses

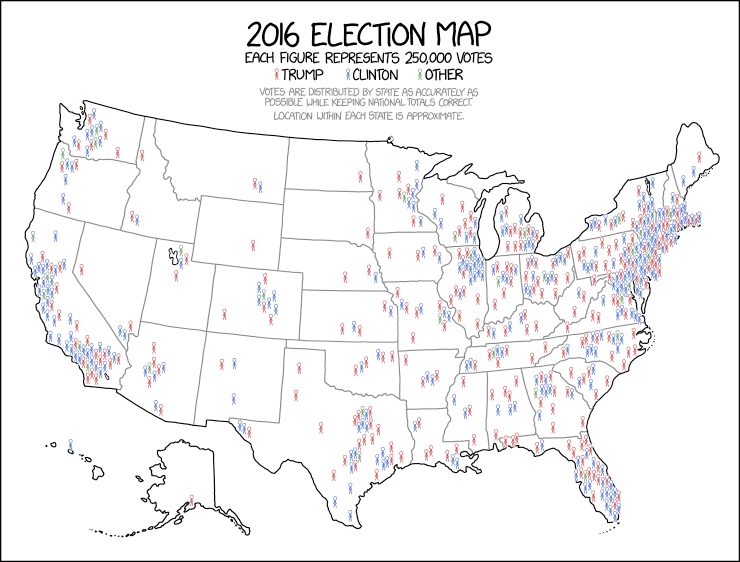

Webcomic XKCD author Randall Munroe produced a nice map by putting people into the geographic map to show both area and population:

Alan Cole argues that it is the best way to draw a political map among several other alternatives that he presents.

Finally, below is a good way to display the house vote in the 2018 midterm election. Unfortunately it overstates the population of places like Wyoming and understates others like the District of Colombia, but that is because our democratic system is biased and this cartogram is accurately displaying the distribution of political power.

Finally, this map of political donations by zip codes shows what a purple country the US is. There are significant red areas in “blue” states and significant blue areas in “red” states.

Update: My next post shows a mmutilitarian map of the world.

Update 2: The Sightline Institute gives several other alternatives.