Before becoming president, Donald Trump was a long-time proponent of single-payer health insurance (aka Medicare for All). That shouldn’t be surprising given that Trump was a liberal Democrat for most of his life until Obama was elected and then Trump’s dislike for Obama seems to have motivated him to become a staunch Republican for the first time. Trump first gained prominence in the party by promoting birther theories against Obama. Trump wrote about single payer at length in a book and repeatedly promised: “We’re going to have insurance for everybody” and “I am going to take care of everybody… The government’s gonna pay for it.”

He campaigned for single payer during the Republican primaries and although he gradually moved towards the standard Republican Party platform, after he became president, he still sometimes praised single-payer systems abroad like the system in Australia.

In today’s USA Today, Donald Trump published an op-ed that has been widely ridiculed for deceptions and/or errors. The Washington Post’s fact checker said, “almost every sentence contained a misleading statement or a falsehood.” Among the falsehoods are targeted attacks on Medicare for All claiming that proponents really want to cut Medicare not expand it. For example, Trump said:

- Democrats favor “eliminating Medicare as a program for seniors”;

- “the Democratic Party’s so-called Medicare for All would really be Medicare for None”

- “under the Democrats’ plan, today’s Medicare would be forced to die.”

This is how he is attacking the people who want to expand Medicare AND make it more generous.

The only age demographic in which a majority consistently opposed Obamacare was Americans older than 65 because they feared that Obamacare might take resources away from their socialized health insurance system: Medicare and Medicaid. US News listed several of the fears that senior citizens have had about that. Seniors were opposed to Obamacare even though it wouldn’t affect them at all largely because the Republican political elite succeeded in making them fear “death panels.” This was the idea that Obamacare would cut lifesaving Medicare benefits. Similarly, organizations like the Heritage Foundation that wants to cut Medicare and Social Security misleadingly criticized Obamacare by claiming it cut Medicare’s generosity to Senior Citizens by $700 billion. In reality, $700 billion was saved through greater efficiency and no benefits were cut. Heritage opposed Obamacare because it was too generous, not because it was spending less, but that would be a political loser, so they made Senior Citizens afraid of benefit cuts instead. Trump’s new op-ed is a another attempt to whip up new fears of death panels. He is literally claiming that Medicare for All would actually mean Medicare for none! This is Orwellian. Up is down!

The Republican party leadership, such as Paul Ryan, has a long history of promoting numerous proposals that really would have cut Medicare spending and privatized it. Ironically, Trump distinguished himself during the Republican primaries by consistently pushing back against that direction of the party elites during his campaign. He was correct when he proudly tweeted:

I was the first & only potential GOP candidate to state there will be no cuts to Social Security, Medicare & Medicaid.

Trump’s generosity towards senior citizen welfare programs is one reason why Trump’s supporters skewed more elderly than previous Republican presidential candidates. But Trump tried to break his signature promise after the election when he promoted every Affordable Care Act repeal proposal, all of which included large cuts to Medicaid.

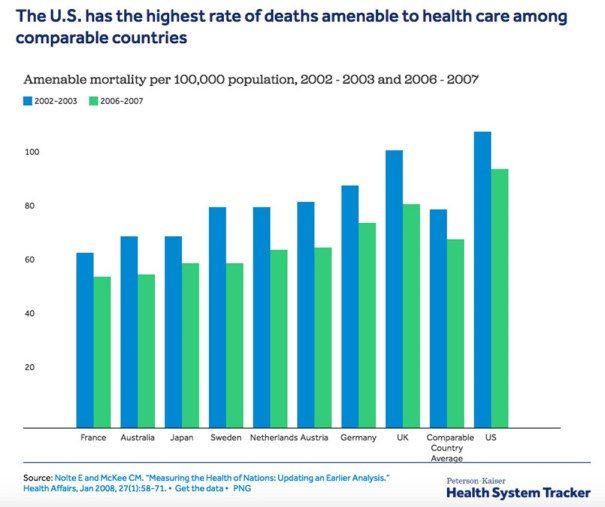

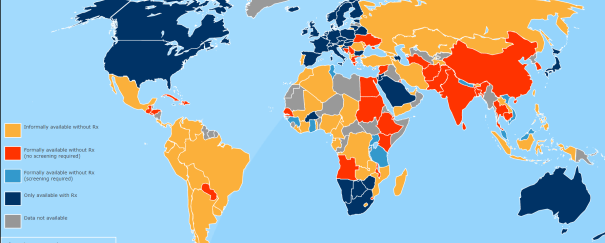

Meanwhile, some studies suggest that one reason the US has lower longevity than any other rich country despite spending more on healthcare (per person) than any other country on earth is that there are many Americans who lack adequate health coverage. Below is one such estimate.

All the other countries have universal health insurance. Maybe we could save lives and cut spending if we copied one of them? The Mercatus Center is another Republican think tank that with similar views to the Heritage Foundation. Mercatus did a recent analysis of single-payer healthcare which was supposed to be critical of it, but actually came to a number of conclusions that make it sound great. They fear that Medicare for All proposals will

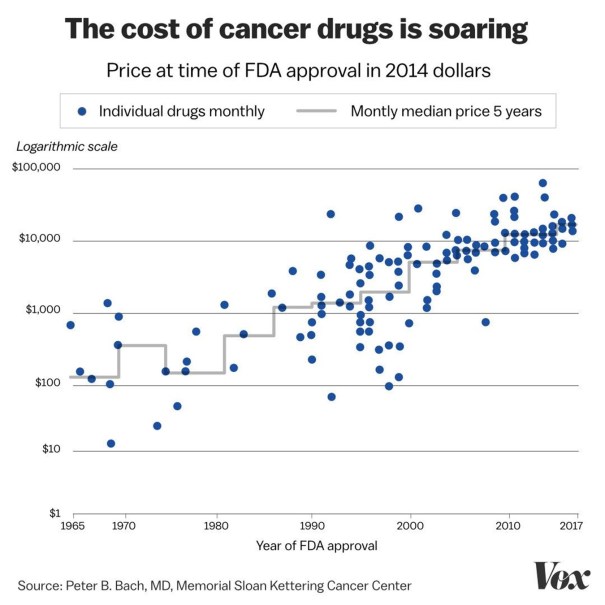

- “substantially reducing drug prices and administrative costs”. Sounds good to me.

- “become responsible for financing nearly all current national health spending.” That implies less out-of-pocket spending, yea!

- “expand the range of services covered by federal insurance (for example, dental, vision, and hearing benefits)” which would be more generous than in most single-payer systems like Canada.

- And reduce overall healthcare spending by over 2 trillion dollars over the first ten years despite more healthcare access! Here is their data in a chart by Kevin Drum:

Of course, they oppose this plan to expand healthcare and lower total spending because

- They think that moral hazard is a huge problem that would only get worse if people had better health insurance. In reality the moral hazard of patients isn’t a significant problem because doctors already ration all the expensive tests and treatments. Patients only have control over relatively cheap office visits and 99% of us don’t wants to go to any more doctor visits than the absolute minimum necessary for our health. Most Americans could probably benefit from more office visits. Other countries with single payer healthcare don’t have a worse problem with it than the US.

- They worry that spending less on healthcare would reduce the quality of healthcare. But for all of you who have a really generous ‘Cadillac-quality’ healthcare policy now, you will still be able to buy a supplemental private healthcare policy that tops off the generosity of the public plan if you want to just like most senior citizens buy supplemental private insurance to top off our existing Medicare insurance. Few people opt for supplemental insurance in nations like Great Britain because most people feel like their free insurance is good enough, but some British citizens want to additional private insurance and they are free to choose to spend more on even better healthcare. Universal healthcare generally only puts a floor on the minimum healthcare citizens can get. The only place I know of where there is any ceiling restricting the maximum is Canada, but I haven’t heard of American politicians proposing any limits on additional insurance that private individuals might want to add to the public plan.

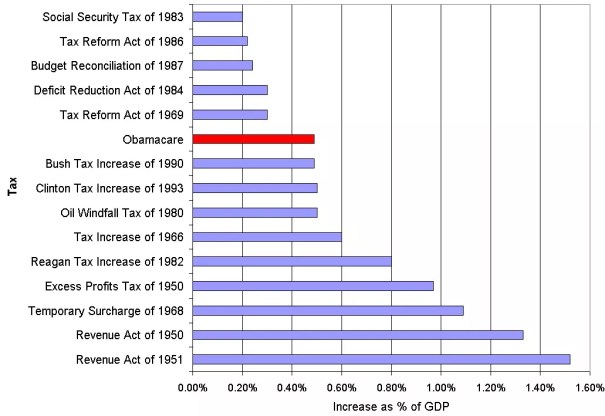

- It would increase taxes massively. Although Americans would have more disposable income on average because private insurance spending would drop more than taxes would go up, Mercatus really, really hates taxes. They are the kind of ideologues who would rather give $10 to a private health insurance company than pay $9 in taxes for a public health insurance plan that gives more coverage! This is also a major reason why they hate Obamacare. Most Americans don’t realize it because most of the burden fell on rich people and corporations, but it was one of the biggest tax increases in American history as this graph from the Incidental Economist shows:

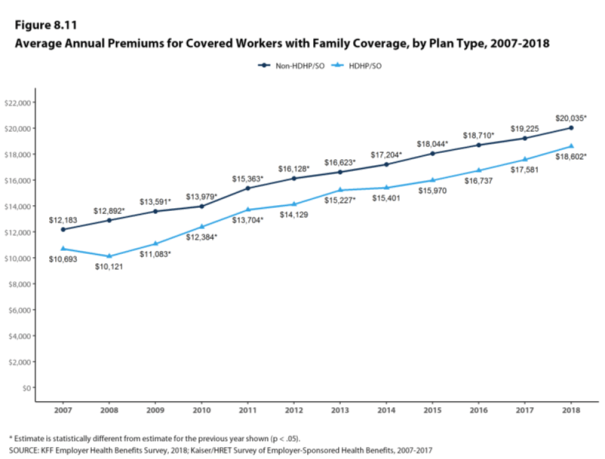

But turning most of the private insurance payroll deduction into a public insurance system would certainly mean that payrolls would have much higher taxes. The average cost of private insurance is over $20,000 per year for an average family policy with normal deductibles and over $18,600 for stingier family policies with high deductibles as the following graph shows. The full cost of healthcare for a family of four is sometimes estimated at about $28,000 per year on average! Even though single-payer would be cheaper, there is no way to replace private insurance without raising taxes a lot. Now, paychecks should still go up after taxes according to this analysis because the new taxes are projected to be less than the insurance they replace, but if you hate paying 95 cents of taxes more than a dollar of insurance payments, then this is a worse scenario.

Ronald Reagan also made similar ‘death panel’-style arguments against the original creation of Medicare in the 1960s. It is humorous in hindsight, particularly when combined with some funny video imagery from the era:*

Whereas Reagan said that Medicare would turn America into a socialist Russia, Trump’s op-ed is warning that it will turn America into a socialist Venezuela! It is the same fear all over again.

But Medicare for All is already much more popular than Obamacare ever was because it is based on a proven program that is even more phenomenally popular, Medicare, and everyone understands what that is. In contrast, Obamacare is confusing and complicated to explain. Some recent polls are finding that 70% of Americans are in favor of Medicare for All versus only 20% opposed.

Although Trump is an incredibly talented salesman, I don’t think his recent death-panel style attack on expanding healthcare coverage will work because Medicare is something Americans already know and love and it will be hard to convince Americans that expanding it is really cutting it.

In the remote chance that the Democrats end up winning a majority of both the House and the Senate in November and thereby getting the power to pass legislation, I’d be surprised if Trump didn’t sign it into law. He is rarely ideologically consistent and he has a long history of supporting this idea. Plus, it would be a great way to become popular and show that he can reach across the aisle to make deals with the Democrats. Ironically, Medicare for All could help him get re-elected in 2020!

Update: Trump’s White House released a book-length whitepaper arguing that Medicare for All would be a disaster because socialism is disastrous. Evidence for this argument includes the horrible famines that happened in the USSR’s Holodomor and Communist China’s Great Leap Forward. And it spends an entire page explaining that it is more expensive to buy and operate a Ford Ranger XL pickup in the socialist hellholes of Scandinavia than in the USA. That should turn some heads on Fox News, but it isn’t clear what it has to do with Medicare. Finally, it argues that Socialist medicine has longer wait times in some other nations than Socialist Medicare has in the US. It seems Trump’s advisers forgot that Medicare is socialist health insurance when they were praising its virtues in comparison with foreign socialist health insurance.

*If you want to hear the complete 12 minute recording of Reagan’s 1961 warning about the evils of Medicare, the original is available from the Reagan Presidential Library. When Reagan made the recording for the AMA, Medicare for All was the original plan and doctors opposed the idea of a universal insurance for all Americans because they were afraid that it would reduce their wealth and power. But Johnson compromised with the AMA and cut back Medicare into a program that only gave universal insurance to the elderly who rarely had been able to afford insurance anyhow. The AMA approved of this change because they figured that providing Medicare only to the elderly population would dramatically raise doctor incomes because the elderly had mostly been previously uninsured anyhow. Reagan also reversed his position from what he said in the above recording and he became such a big supporter of Medicare that he raised the payroll taxes that fund it (and Social Security) by more than any other president. He also tried to expand Medicare to cover pharmaceuticals and more.

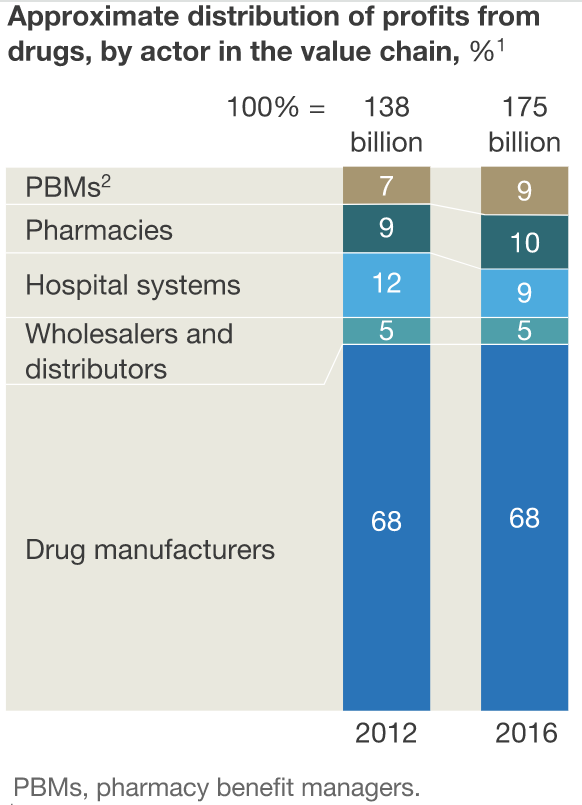

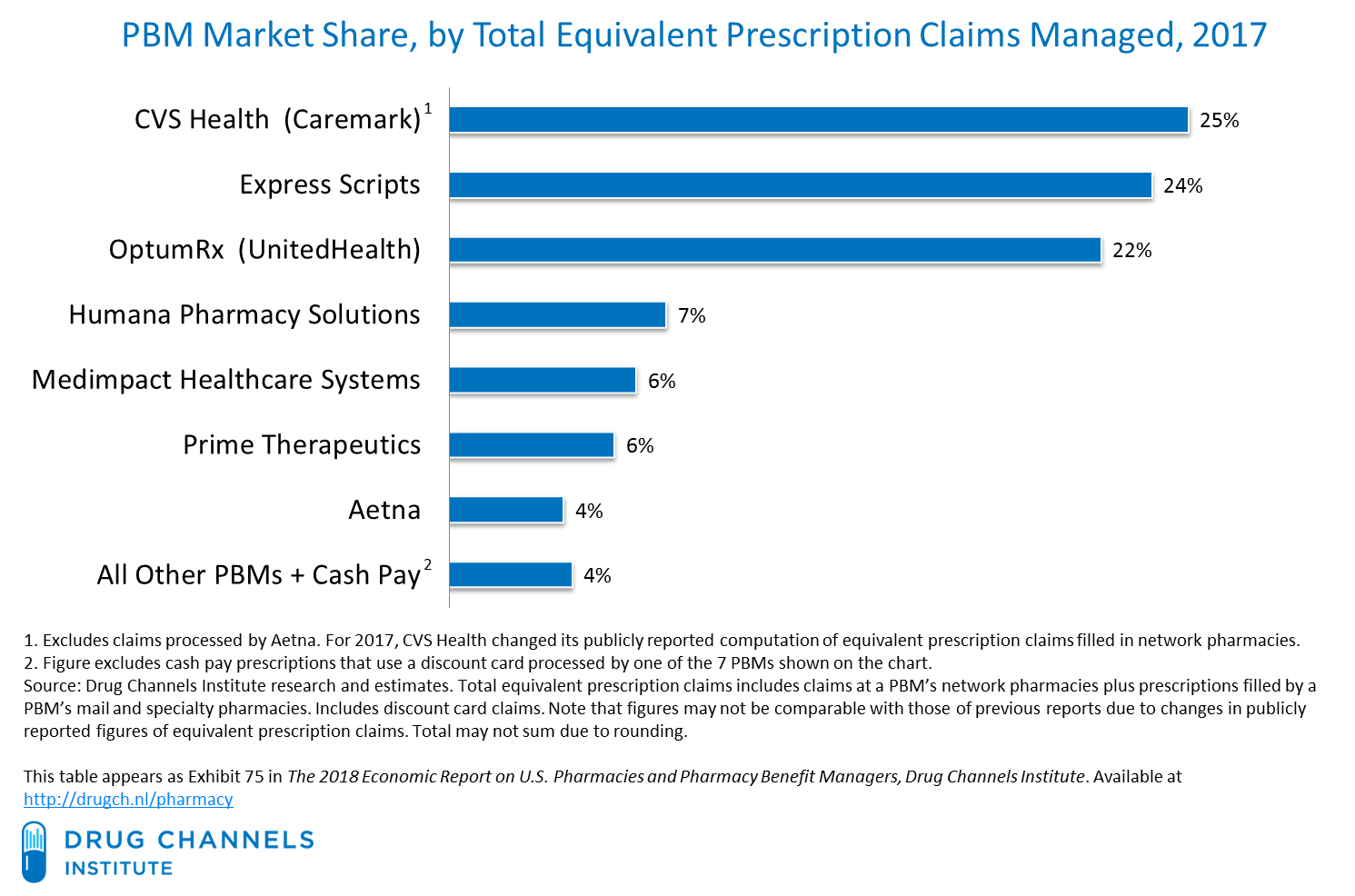

At this point already, all the pharmacies other than CVS just have two big independent PBMs that they can work with and all the health insurers other than UnitedHealth also just have two big independent PBMs. I predict that Walgreens (

At this point already, all the pharmacies other than CVS just have two big independent PBMs that they can work with and all the health insurers other than UnitedHealth also just have two big independent PBMs. I predict that Walgreens (