Back in 2011, which kind of license would cost more money to obtain in New York City,

A) a license to practice medicine

or

B) a license to drive a taxicab?

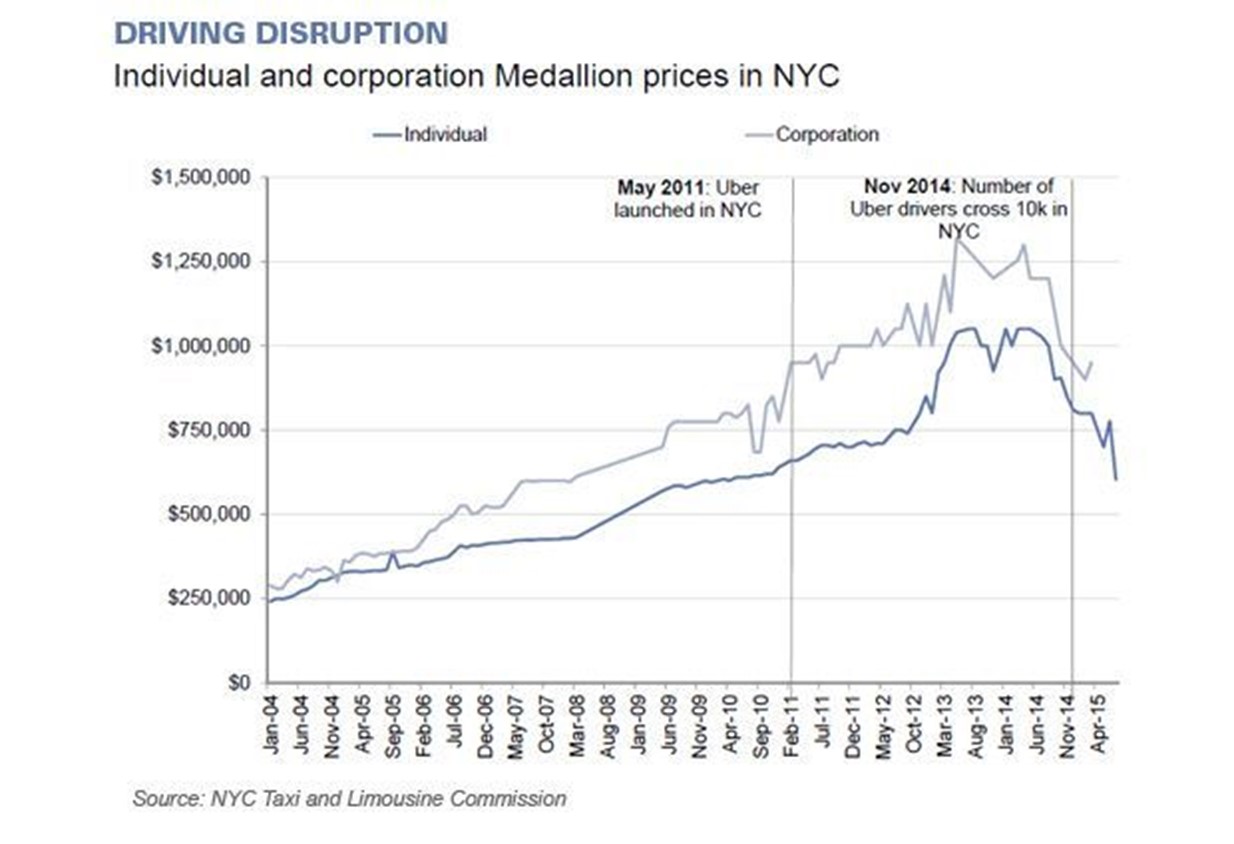

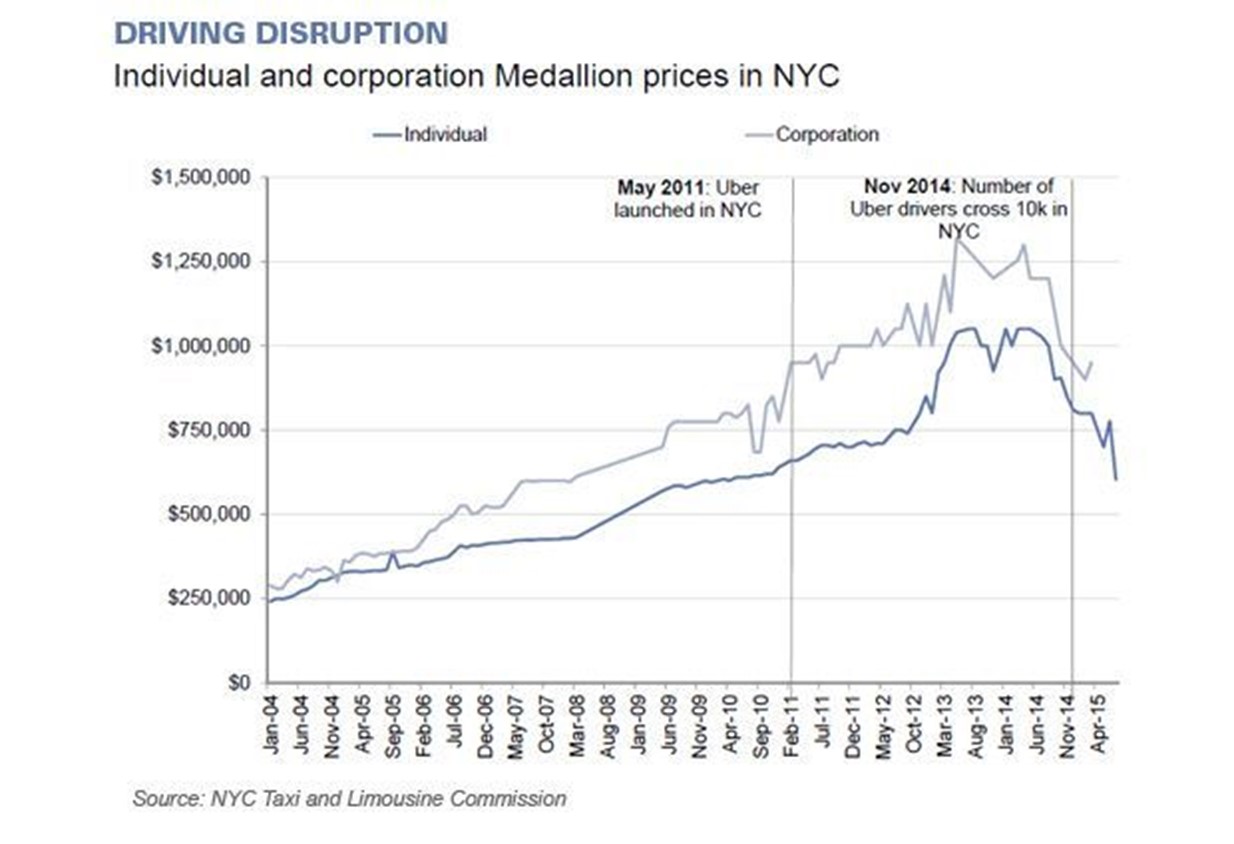

In 2011, a taxi cab license cost over $1 million. That was about eight times more than doctors had been paying for their medical licenses. According to the AMA, the average debt facing medical doctors graduating in 2009 was only $156,000 plus out-of-pocket tuition averaging approximately $45k according to my calculations. Meanwhile, in 2012, New York City had hundreds fewer cab licenses than it had in 1937! Taxicab license owners caused a shortage of taxis and bad taxi service because of low availability and high prices.

The reason there is a BIG difference in pay for doctors versus taxi drivers is that that each worker was licensed in medicine whereas each vehicle was licensed for taxis. The owners of scarce resources get the income boost, so whereas doctors owned the scarce ability to practice medicine, the owners of the taxis owned the chokepoint and got most of the taxi revenues. The wealthy taxi owners typically rent out the vehicles to low-paid drivers and extract most of the profits from the high taxi fares.

Occupational licensing is growing

Adam Smith famously said, “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.” Occupational guilds are an ancient example and modern licensure in the USA dates back to the Flexner Report in 1910 which exposed poor quality doctors and medical education. It described medical schools as, “private ventures, money making in spirit and object… No applicant for instruction who could pay his fees or sign his note was turned down.” Anyone could practice medicine whether they had any education or not. The Flexner Report led to licensure of medical doctors and medical schools which dramatically raised the standard of care and wages. Other occupations soon copied the same strategy.

James Bessen wrote :

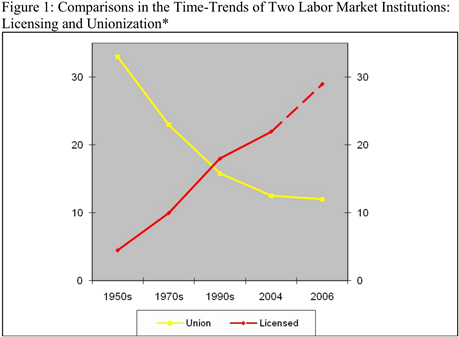

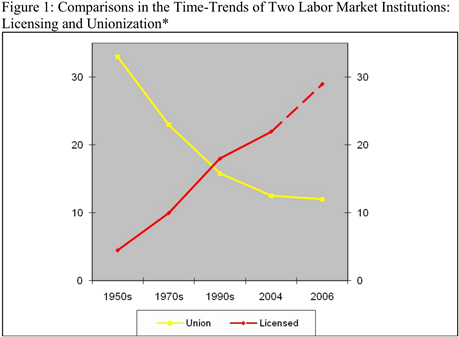

In the 1950s, only 70 occupations had licensing requirements, and these accounted for 5 percent of all workers. By 2008, more than 800 occupations were licensed in the various states and they accounted for 29 percent of all workers. Licensed occupations include everything from barbers and interior designers to nurse practitioners and physicians.

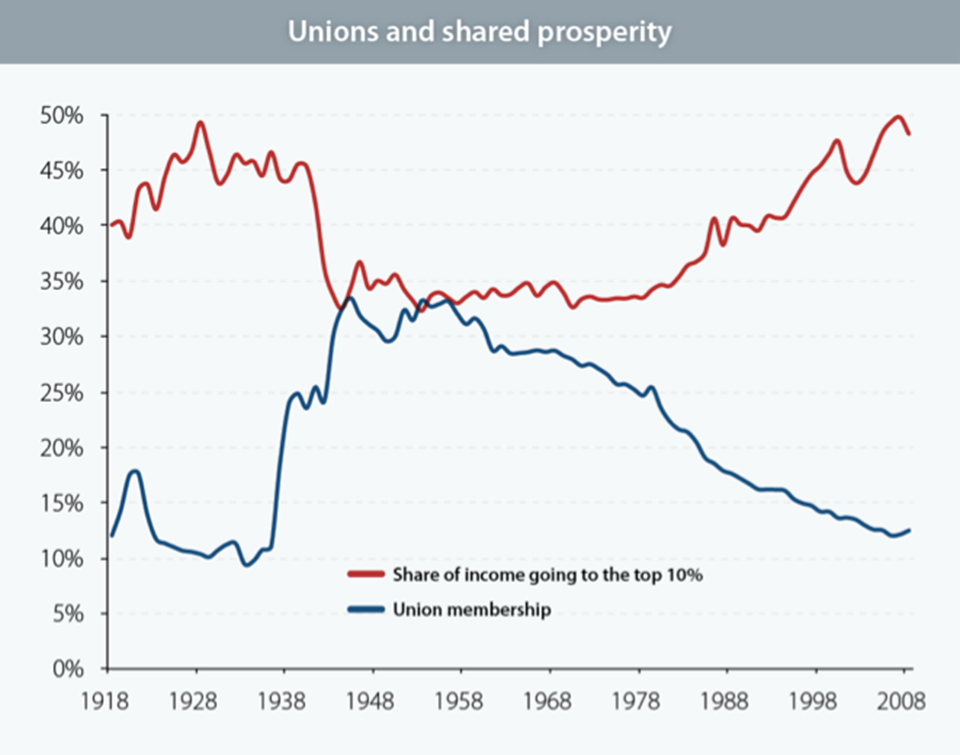

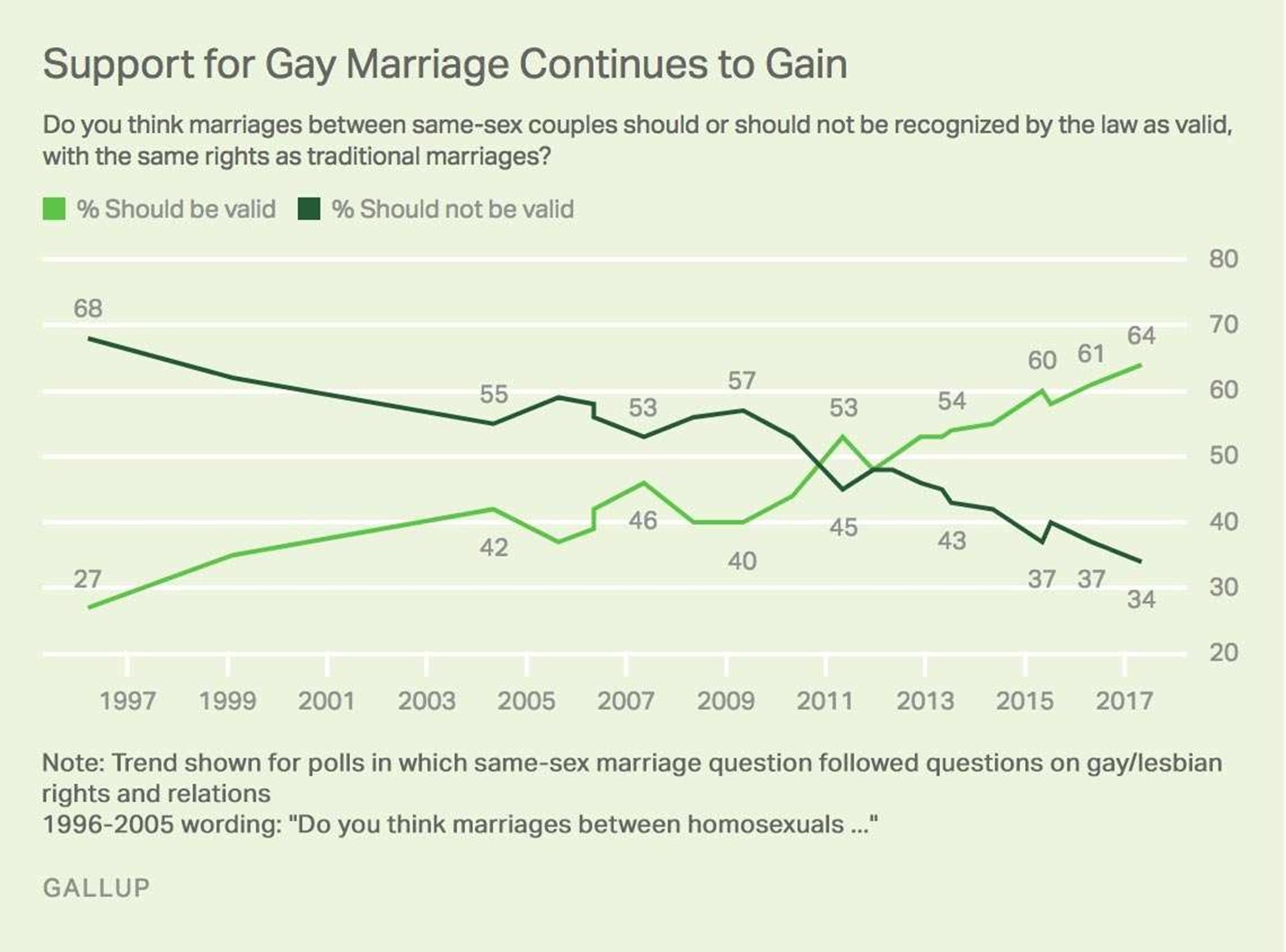

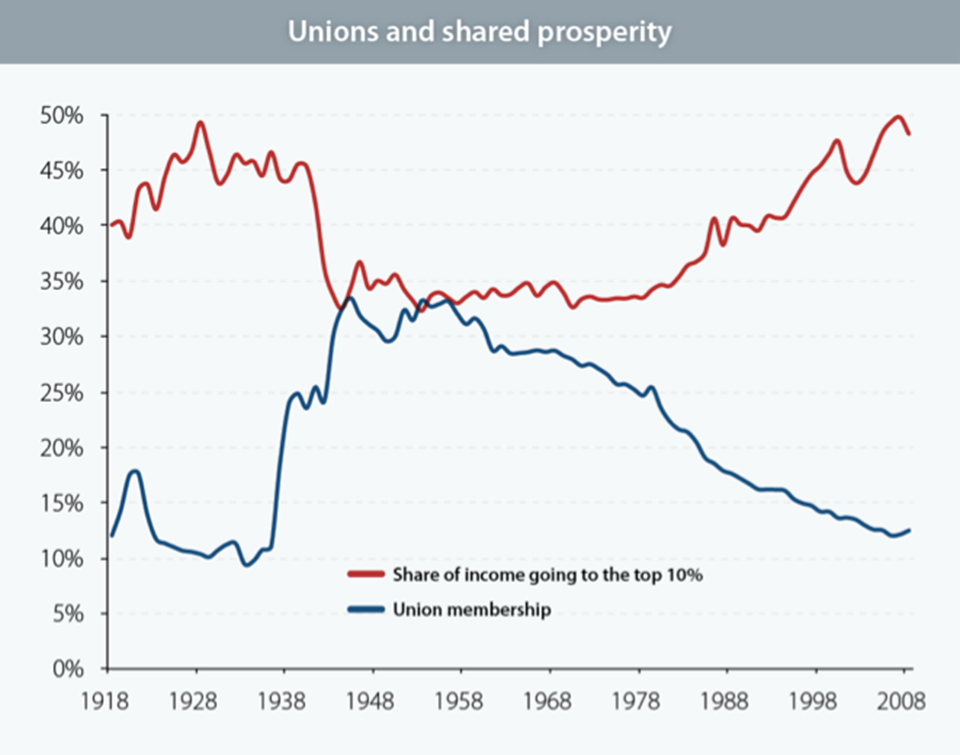

Whereas 35% of Americans working for the private sector were union members in the 1950s, by 2017, that number dropped to only 6.5%. Today licensure has replaced unions as the main mechanism whereby workers band together to raise their wages as demonstrated by the following graph by Morris Kleiner and Alan Krueger:

Kleiner and Krueger found that licensure boosts wages about 15% which is similar to what unions achieve for workers. As of 2008, 29% of workers had a government license for their job.

Unfortunately, the economics textbooks are still stuck in the 1950s. Uwe Reinhardt surveyed labor economics textbooks and found that the median amount devoted to unionization was an entire chapter versus zero pages about occupational licensure.

Mechanisms for restricting competition

Licensing boards limit competition through various kinds of requirements:

- Training programs. They regulate accreditation of schools and/or limit the number of openings available for incoming students.

- Experience as a low-paid apprentice to a licensed practitioner. This creates a barrier to entry and directly boosts the income of the cartel members by giving them cheap labor. At one time, it took longer for an apprentice to become a master plumber in Illinois than for a medical student to become a Fellow of the American College of Surgeons after getting the basic medical degree. Physician interns are routinely kept awake for 24hr shifts which may lead to increased patient deaths because “practicing medicine while

sleep-deprived is akin to working while drunk.” There is no educational rationale for making the least experienced doctors work while fatigued and sleep deprived, but many doctors who have passed through this initiation rite defend it with cult-like devotion and it does provide a lot of cheap labor for their supervisors and makes a great barrier to make it harder to become a doctor. Medical students typically work 80 hours per week on shifts often lasting 24 hours at a time for years during their residencies and that reflects a considerable cutback due to new regulations in the 2000s.

- Entrance exams. Licensure boards often make exams harder to reduce competition, but none of the existing practitioners ever has to retake the new “improved” exams. Some exams have little relationship to the actual services of the occupation. For example,

- Fees. This both creates a barrier to entry and helps fund the professional organizations that maintain the barriers to entry.

- Personal characteristics: Age requirements, citizenship, residence, bans on ex-convicts, etc. Many of these requirements are unconstitutional, but they often remain on the books in many states because the people who are hurt by these restrictions (unlicensed workers and consumers) do not challenge the laws in court.

- Operating separate requirements in each state to prevent competition from people in other states. This makes life particularly hard for military spouses that move frequently across state lines which makes licensure nearly impossible. And servicemembers also learn valuable expertise in the military, but after discharge, their military training rarely qualifies them for a civilian license in their home state.

Licensing increases wages for practitioners by raising costs for consumers.

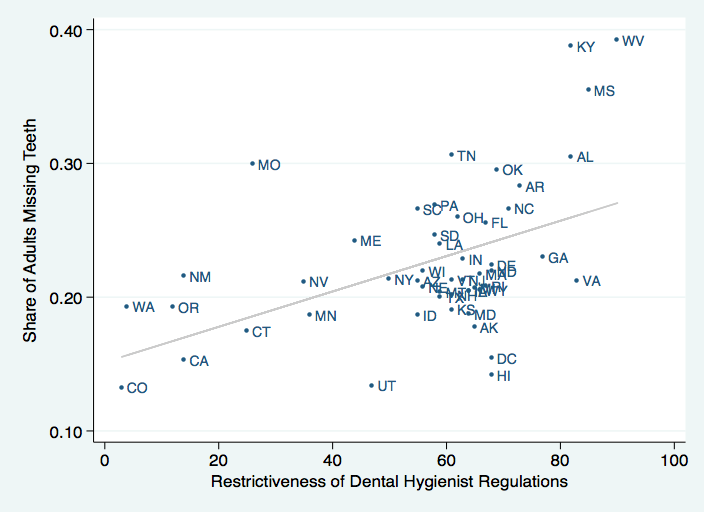

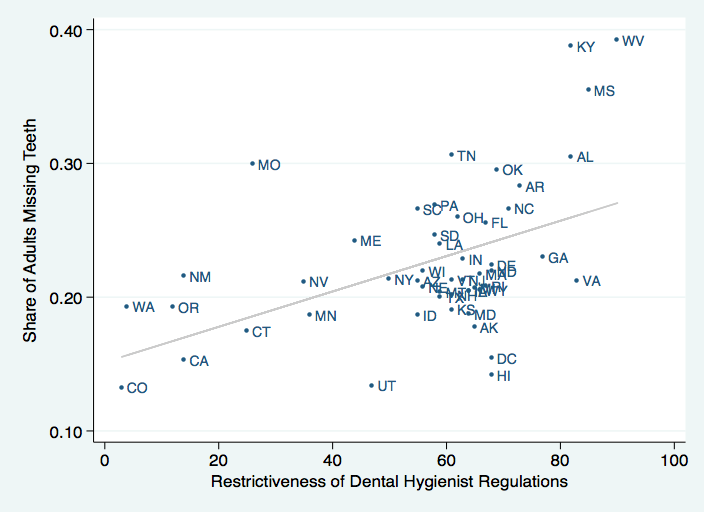

A third of Americans don’t get dental care each year and the main reason Americans get poor dental care is high costs. For example, a study of Air Force cadets found that cadets from states that have stricter licensure for dentists did not produce better dental health. James Bessen:

Dentistry provides a striking example of how excessive regulation can harm patients. Dental fees are substantially higher in states that do not recognize out-of-state licenses for dentists. The Federal Trade Commission found that just the regulations on the roles of dental hygienists and the numbers working per dentist raised dental fees by 7 to 11%. Excessive licensing also reduces access to services. Facing higher fees, consumers purchase fewer services, including health care. State regulations on dental hygienists have been shown to be associated with fewer office visits, which can lead to poorer health. …The figure shows that on average, states with stricter regulations of dental hygiene perform worse on one measure of oral health: the percentage of adults who have lost teeth from tooth decay or gum disease. Dental hygienists provide preventive care that can avert tooth loss. States with the most restrictive occupational regulations have about twice as many adults who have lost teeth. While factors other than regulation affect oral health, careful studies (and this one) find a robust relationship between regulation and access to care.

…The figure shows that on average, states with stricter regulations of dental hygiene perform worse on one measure of oral health: the percentage of adults who have lost teeth from tooth decay or gum disease. Dental hygienists provide preventive care that can avert tooth loss. States with the most restrictive occupational regulations have about twice as many adults who have lost teeth. While factors other than regulation affect oral health, careful studies (and this one) find a robust relationship between regulation and access to care.

In some states, dental hygienists can work independently of dentists and in other states, they can only work for a dentist. Forcing dental hygienists to work for dentists, increases the wages of dentists and reduces the wages of dental hygienists thus harming dental patients by reducing affordability. There is a similar dynamic happening by forcing nurse practitioners to work under the supervision of doctors. For example, nurse practitioners in North Carolina pay about $12,000 per year to doctors to sign forms to permit the treatments the nurse practitioners are trained to provide. In 22 other states they have “full practice authority” to work independently.

Sidney Carroll and Robert Gaston found that electrocution rates are higher in states with more restrictive licensing laws for electricians possibly because there is more do-it-yourself electrical work where it is harder to hire a professional. James Bessen says there is no measureable relationship between quality and licensure of interior decorators:

In the states where [interior decorators are licensed, they] are required to pass a national exam, pay fees, and devote six years to education and apprenticeship. Yet studies show little safety or quality benefits: interior decorators do not have lower insurance premiums, lower rates of fire deaths, or fewer complaints to the Better Business Bureau in states that impose these requirements.

The transitional gains trap of licensure

Usually a new licensure system ‘grandfathers’ all the existing workers and only applies to newcomers. The way it works is that a group of professionals like hairdressers meets for a state convention and decides to lobby the government to make licensure mandatory. The new fees and requirements reduces the supply of hairdressers and raises wages, but the newcomers don’t really benefit from the boost in wage because it just becomes a compensating wage differential that matches the amount they paid to get the licensure.

Gordon Tullock calls this the transitional gains trap of licensure. When licensure limits the supply of workers and raises wages, the 1st generation of incumbent workers benefit from licensure because they are grandfathered in and do not have to pay a price for licensure and purely benefit from the higher wages caused by limited supply.

Subsequent generations don’t benefit from higher wages because they have to pay the price of licensure. But after they have paid the price, they want to keep licensure because they do not want additional competition.

Thus, it is a trap that only gives a transitory benefit to the first generation and no benefit to subsequent workers, but they want to keep it nonetheless.

Political determinants

The Institute for Justice is fighting to reduce occupational licensure requirements and they ranked the states using various metrics to assess which states have the most burdensome licensure. Can you guess whether conservative states or liberal states have more burdensome regulations? It turns out that there is no discernable partisan tendency. Some states simply have more organized professional associations. A 1991 study found that the main reason for differences in licensure requirements between states was whether a local professional association funded a lobbying effort to require licensure in each state.

Licensing requirements are often irrational and enforcement is bizarre

The White House CEA found that there is too much variance in licensing requirements in different states to be explainable by any rational need for the requirements.

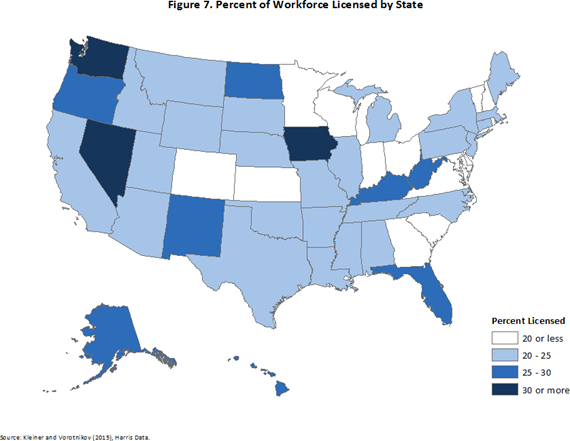

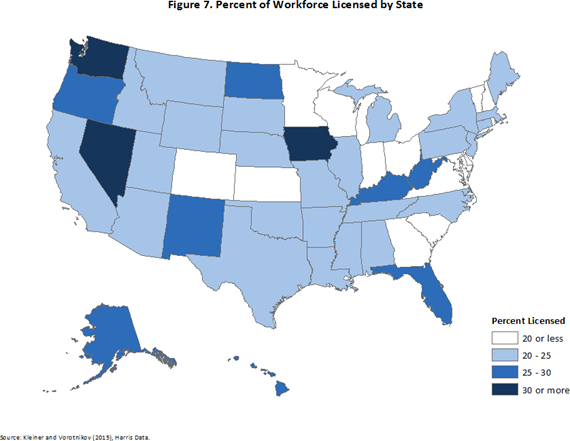

Estimates suggest that over 1,100 occupations are regulated in at least one State, but fewer than 60 are regulated in all 50 States, showing substantial differences in which occupations States choose to regulate. For example, funeral attendants are licensed in nine States and florists are licensed in only one State. The share of licensed workers varies widely State-by-State, ranging from a low of 12 percent in South Carolina to a high of 33 percent in Iowa… States also have very different requirements for obtaining a license. For example, Michigan requires three years of education and training to become a licensed security guard, while most other States require only 11 days or less. South Dakota, Iowa, and Nebraska require 16 months of education to become a licensed cosmetologist, while New York and Massachusetts require less than 8 months.

Licensure requirements are sometimes bizarre:

Entrepreneur Taalib-Dan Abdul Uqdah runs Cornrows and Company, a Washington, D.C., salon that specializes in braiding the hair of black women. Starting with $500 in 1980, Uqdah had created a $500,000-a-year hair-care business by 1991. He refuses to use chemicals and, instead, weaves the hair into hundreds of tiny braids. The District of Columbia government has tried at least four times to prosecute Uqdah for operating his shop without a license. Anyone who works with hair in D.C. must spend nine months in cosmetology school, at an out-of-pocket cost of about five thousand dollars. Yet such training would be useless for Uqdah and his employees because the schools do not teach his methods; because braiding does not use chemicals, it is not regarded as cosmetology. Uqdah tried to get the law changed by having the D.C. Board of Cosmetology create a license for braiding, but the board refused. When he appealed to the City Council, the board successfully lobbied against him. The board recently fined him one thousand dollars for “operating an unlicensed beauty shop.” At this writing he faced the possibility of a prison sentence.

Yes, cutting hair without a license can lead to jail time. It can even bring on the SWAT teams:

In Florida, up to 14 armed police raided over 50 barbershops in predominantly black and Hispanic neighborhoods without warrants. The police were in SWAT gear, armed with masks and guns and police dogs, according to Reuters. Over 30 barbers were handcuffed, in front of customers, on criminal charges of barbering without an active license.

At one barber shop, the scene looked like this:

They blocked the entrances and exits to the parking lots so no one could leave and no one could enter. With some team members dressed in ballistic vests and masks, and with guns drawn, the deputies rushed into their target destinations, handcuffed the stunned occupants — and demanded to see their barbers’ licenses…

the shop was filled with anywhere from ten to twenty-five waiting customers. As the first day of the school year was approaching, several of the customers in the shop were children… The officers immediately ordered all of the customers to exit the shop and announced that the shop was “closed down indefinitely.” …Anderson was handcuffed by a masked officer…

While Trammon, Anderson, and Berry were restrained [in handcuffs on the floor], Inspector Fields and the OCSO officers conducted their “inspection” of the barbershop. …At the conclusion of the inspection, it was determined that all of the barbers had valid licenses and that the barbershop was in compliance with all safety and sanitation rules. No criminal violations were discovered, and Berry, Anderson, and Trammon were released from their handcuffs…

Whereas the police do not help unions bust their competition, the strong arm of the government does the expensive dirty work of keeping outsiders from competing for work against the wishes of licensure organizations. Most Americans seem content with this arrangement because they are told that it help them get higher quality services.

Medical and legal services have the most licenses

Milton Friedman wrote:

“Would it not… be absurd if the automobile industry were to argue that now one should drive a low quality car and therefore that no automobile manufacturer should be permitted to produce a car that did not come up to the Cadillac standard. …[Doctors] argue that we must have only first rate physicians even if this means that some people get no medical service—though of course they never put it that way.

Once when Friedman told this to a group of lawyers, one of the lawyers said that we SHOULD only accept the best quality (Cadillac) lawyers. The lawyer unabashedly argued that we should ban mediocre-quality legal services because anything but the best would be too dangerous to the public. The Economist magazine disagrees because US lawyers have a greater monopoly on preventing competition than almost any other profession rivaled only by healthcare.

Almost every American state forbids those who do not have a three-year law degree from providing most legal services. Bar associations—composed of lawyers themselves—often define what counts as legal practice. In 2000 the American Bar Association, after rejecting a proposal to allow lawyers to split fees with non-lawyers, asserted that “the maintenance of a single profession of law” was a core priority. “In no other country does the legal profession exert so much influence over its own regulatory process,” writes Deborah Rhode of Stanford University in her book “The Trouble with Lawyers”. Outsiders typically cannot even invest in law firms, limiting funding for innovative new business models, such as providing fixed-fee legal advice over the internet, or through retailers. Even those who are qualified can struggle to compete across state boundaries, because of the need to pass a separate bar exam.

Advocates for reform compare America’s model unfavourably with that of Britain. There, non-lawyers have a built in majority on legal regulatory bodies, which are tasked with promoting competition as well as protecting consumers. Outside court, anyone can offer legal advice, or provide basic legal services like drafting documents. The result seems to be cheaper access to justice, and more innovation. The World Justice Project ranks America 96th of 113 countries for access to and affordability of justice, sandwiched between Uganda and Cameroon. (It does not help that there is hardly any legal aid [for people who cannot afford a lawyer in the USA].)

And because legal services are much more expensive in the US than in other nations, the meagre legal aid does not stretch to serve very many people.

The supposed rationale that every professional organizations has for is licensure requirements is to increase quality. However, there is scant evidence that most licensure requirements produce benefits at all and when there are benefits, they rarely suffice to justify the increased costs. If professional organizations really wanted to increase the quality of their services (rather than just increase their incomes) a more important way to prevent bad quality work would be to punish professionals who do bad quality work. Unfortunately, as S. David Young explains, that rarely happens.

licensing agencies are usually more zealous in prosecuting unlicensed practitioners than in disciplining licensees. Even when action is brought against a licensee, harm done to consumers is unlikely to be the cause. Professionals are much more vulnerable to disciplinary action when they violate rules that limit competition. A 1986 report issued by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services claims that despite the increasing rate of disciplinary actions taken by medical boards, few such actions are imposed because of malpractice or incompetence.

The evidence of disciplinary actions in other professions, such as law and dentistry, is no less disturbing than in medicine. According to Benjamin Shimberg’s 1982 study, for example, as much as 16 percent of the California dental work performed in 1977 under insurance plans was so shoddy as to require retreatment. Yet in that year, the dental board disciplined only eight of its licensees for acts that had caused harm to patients.

Licensure associations are happy to send the SWAT teams out to bust unlicensed workers (regardless of whether they are doing quality work), but they can hardly be bothered to investigate dangerous quality work of card-carrying members of their association.

The following graph from Thomas Getzen shows the number of new medical doctors in the US. The Health Professions Educational Assistance act of 1963 & 1965 increased the number of medical schools in the United States and over the following two decades, the number of students in US medical schools doubled and new physicians entered the workforce at three times the rate that older doctors left practice. Then in 1982, the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee (GMENAC), recommended that U.S. medical schools decrease enrollment levels by 10 percent relative to the 1978 level and for three decades, there was less production of new medical doctors than there was in the 1970s even as the demand for doctors continued to grow.

Between 1978 and 2008, the population grew 36%, the average age of the population rose, and new technologies like the MRI were developed, all of which increased the need for US doctors even though the medical cartel did not increase production.

This is why the US has fewer doctors per capita than all other rich nations except Japan, Canada, and Singapore. Although the US is far behind almost all rich nations, Americans can take comfort in knowing that at least America surpasses most poor countries as shown in the World Health Organization graph below. Darker colors mean more physicians per 1,000 people. Cuba tops the list with almost three times more doctors per capita than the US. Whereas the US doctor shortage created in the above graph, makes the US a huge importer of doctors, Cuba has a comparative advantage in producing doctors and is a major exporter of doctors’ services. In 2014 the Cuban government had contracted out 37,000 doctors working in 77 countries generating $8 billion in foreign exchange plus there were many more doctors that permanently emigrated from Cuba. Over 7,000 Cuban healthcare professionals had come to work in the US as of 2015.

Not only does the American medical cartel determine the number of US medical school graduates, they also get the government to pay the bulk of the costs of educating doctors through various subsidies. Yes, medical school students pay a lot for tuition, room, and board over the seven years or more that it takes to become a doctor. I estimated above that medical school students paid roughly about $200,000 in 2010. But medical school is taught by top doctors with small classes. You know how much a 15-minute office visit with a specialist costs? Well medical school is as expensive as spending hours every day with top specialists for a minimum of seven years plus several more years for doctors who want to become specialists themselves. Most of that is paid for by the government via Medicaid and Medicare payments for patient fees at teaching hospitals, research grants, and other subsidies.

Not only does the US have fewer doctors than most rich nations, the US had more doctors in the 1800s according to census data:

The rise since 1980 was mostly due to an increase in immigration of foreign doctors to the US. For example, 55% of the increase in doctors from 2000 to 2007 in the US were immigrants from foreign countries. In contrast to a century of declining numbers of doctors, the quantity of nurses exploded over the same time period which is only natural given the rapid rise in healthcare expenditures and services during this time. According to this data, we had over five nurses for each physician in the US in 2000.

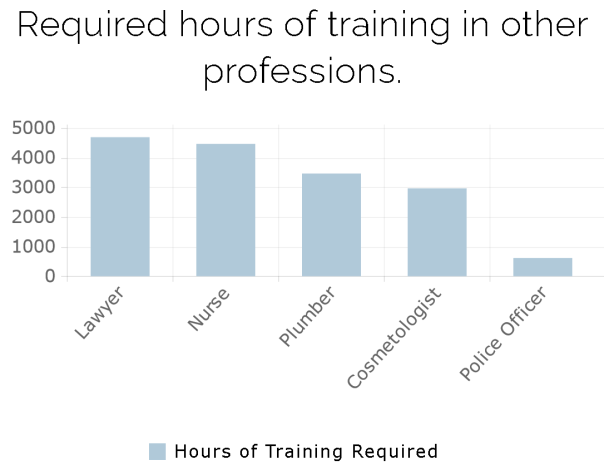

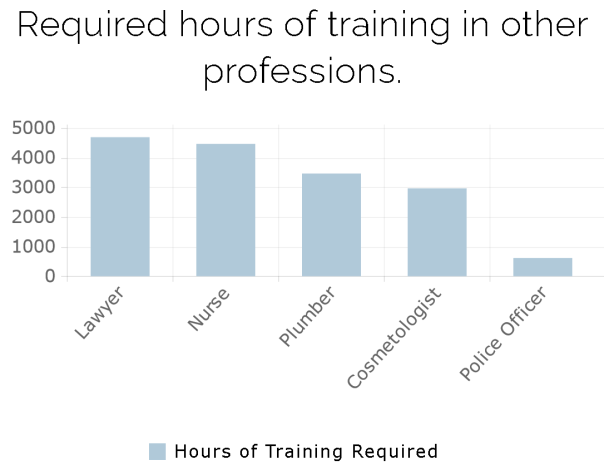

Police have much less training than you would expect!

Whereas some occupations have too much licensure requirements others may have too little. As Colin Kaepernick said, “You can become a cop in six months and don’t have to have the same amount of training as a cosmetologist. That’s insane. ”

Police officers get far more training in most nations of the world. The US also has a much bigger problem with police killing civilians than in other rich countries, so perhaps policing is one area where stricter licensure standards would be beneficial.

Inequality

The Economist magazine points out that whereas unionization tended to decrease inequality, many kinds of licensure has the opposite effect:

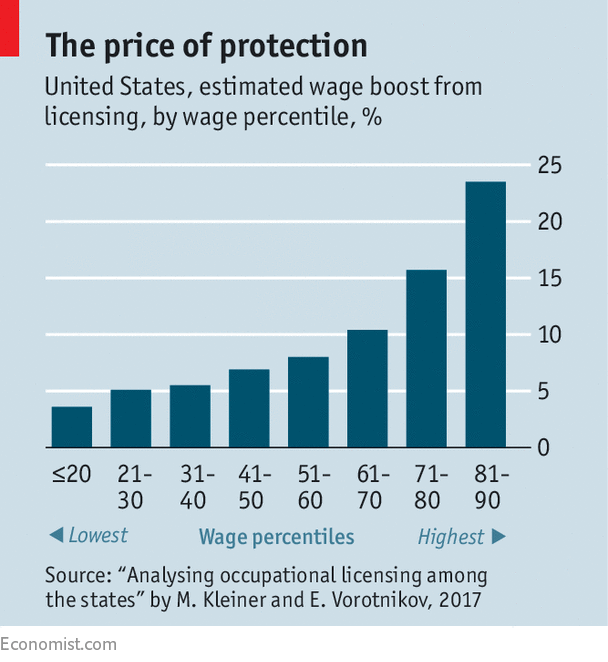

Lobbyists justify licenses by claiming consumers need protection from unqualified providers. In many cases this is obviously a charade. Forty-one states license makeup artists, as if wielding concealer requires government oversight. Thirteen license bartending; in nine, those who wish to pull pints must first pass an exam. Such examples are popular among critics of licensing, because the threat from unlicensed staff in low-skilled jobs seems paltry. Yet they are not representative of the broader harm done by licensing, which affects crowds of more highly educated workers like Ms Varnam. Among those with only a high-school education, 13% are licensed. The figure for those with postgraduate degrees is 45%.

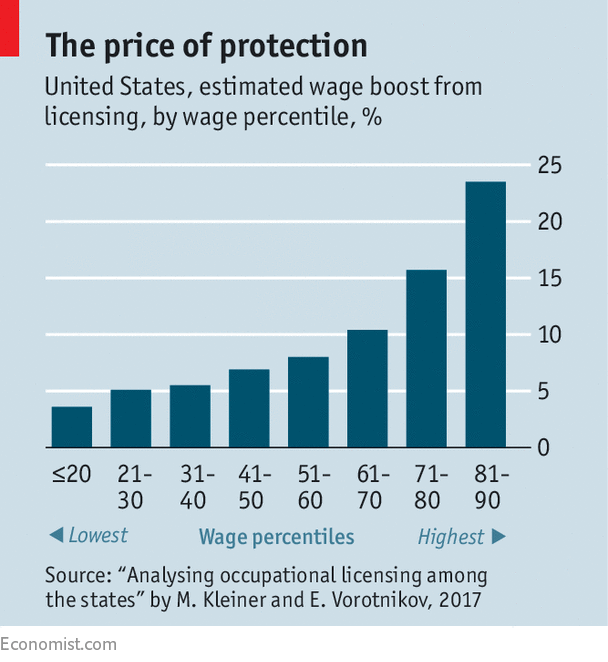

More educated workers reap bigger wage gains from licensing. Writing in the Journal of Regulatory Economics in 2017, Morris Kleiner of the University of Minnesota and Evgeny Vorotnikov of Fannie Mae, a government housing agency, found that licensing was associated with wages only 4-5% higher among the lowest earning 30% of workers. Among the highest 30% of earners, the licensing wage boost was 10-24% (see chart 1). Forthcoming research by Mr Kleiner and Evan Soltas, a graduate student at Oxford University, uses different methods and finds no wage boost at the bottom end of the income spectrum, but a substantial boost for higher earners.

The medical and legal professions [are the most dominated by licensure and they] account for around a quarter of the top 1% of earners, whose incomes have grown faster in America than in other rich countries in recent decades. A study published in Health Affairs, a journal, in June 2015 found that the average doctor earns about 50% more than comparably educated and experienced people in other fields. Another study, from 2012, put the wage premium from working in law at 23%.

[American] Doctors are also unusually well-paid compared with …other countries. The average general practitioner earns $252,000 and the average specialist $426,000 [in America. That is approximately double the average salaries in other rich nations after adjusting for living costs].

More competition would surely bring both wages and prices down. And less licensing across the board would make entrepreneurship easier. It might even palliate populism, which is partly driven by voters’ sense that the economy is rigged to benefit the rich and powerful—a hypothesis which the evidence on licensing plainly supports.

The following graph shows that there are some people working in healthcare and the legal professions whose jobs do not require licensure, but they typically work for bosses who have a license and use it to squeeze more money out of the industry so licensure increases inequality even when you just examine inequality among workers within industries like healthcare and the law.

Whereas the old manufacturing unions organized low-paid assembly-line workers so that they could negotiate more money out of their bosses, licensure often works the opposite way. Licensure in law and medicine would be more analogous to a manufacturing system whereby the factory owners banded together to prevent competition from outsiders and achieve greater control over their workers by lobbying the state to enforce regulations that give the factory owners greater control over what happens in the manufacturing industry.

Most union jobs do not required workers to pay for testing, training, and apprenticeships before they can join. In contrast, the rising share of American jobs that require licensure are only accessible to people with the time and money to complete lengthy licensing requirements. One study found that even for a subset of low- and medium-skilled jobs, the average license required around 9 months of education and training. That is fine for people with time and money, but it could create a kind of poverty trap for less fortunate workers.

One of the most remarkable features of the US economy was the dramatic drop in inequality that happened beginning around the end of the Great Depression through WWII as you can see in the red line in the graph below.

One of the factors that might have contributed to the fall and then rise in American inequality is the rise and then fall in unionization. As unions have disappeared since the 1970s, licensure has been growing and has replaced unions as the dominant way workers have been organizing, but licensure had had the opposite effect on inequality. This is not to say that unionization and licensure are THE cause of inequality, but they likely contribute.

Taxi cab licensure is a good case in point showing how licensure can increase inequality. Taxi licensure likely began when cab drivers banded together to limit the number of cabs and control the quality of the vehicles. Unlike most forms of occupational licensure, it doesn’t directly restrict the people who can do the work. It restricts the vehicles that can do the work.

As the value of cab licenses or “medallions” rose, their ownership became too expensive for cab drivers to afford. Only a multi-millionaire can afford to invest in a medallion for a single taxi that costs $1.25million. Cab drivers had to rent a medallion to be able to work. Renting the medallion became the most expensive part of cab driving in New York City and elsewhere with medallions. The medallions became more valuable as the demand for cabs rose because the supply of cabs was fixed and that increased the price of cab fares. That was also what made this market so appealing for disruption by Uber and Lyft which destroyed the value of medallions by getting around this licensure restriction and offering lower fares.

The medallions ended up increasing inequality because the millionaires who owned them got all the benefits of the higher prices. The taxi drivers had to pay the medallion owners a lot more of their fare money than they got to keep even though they did all the work. The medallion owners defended the system by arguing that it was necessary to ensure the quality of taxis, and it is true that they had some interest in preventing the worst kind of quality problems, but the licensure system was a kind of cartel which has zero incentive to reduce prices and only very minimal incentive to improve quality.

The laziness of the taxi cartels was one reason Uber was able to destroy them. Their monopoly power had provided no incentive to improve and they were offering mediocre quality at a very high price. Unfortunately, Uber did not fix the inequality issue. Uber drivers probably earn even less than the cab drivers because Uber has figured out how to take advantage of the fact that most drivers fall prey to the hidden-cost fallacy and don’t factor in any cost of capital for vehicle depreciation per mile.

MIT estimated that the median pay for Uber in the US is about $3.37 per hour! Larry Mishel of EPI estimated that Uber drivers earn $9.21/hour and Noah Smith estimated that it might be as high as $10 per hour which is much better, but that would still put full-time drivers at the poverty line unless they were single adults without any dependents. Most drivers quickly figure out how bad the pay is and that is why 96 percent of Uber drivers quit working for Uber in less than a year.

Voluntary Certification vs. Mandatory Licensure

The bachelor’s degree is a certification that gives a signal of worker quality, but it is purely voluntary. Any employer can choose whether to hire someone with this certification or not. Workers with bachelor’s degrees earn about 80% more than workers without, so it is a valuable certification, but nobody has to pay this wage premium. Most workers do not have this certification and anyone can hire them, so the only reason to pay extra is because people with a bachelor’s degree are more productive and this gives an incentive for people to learn productive skills in getting their degree.

Licensure eliminates the choice whether to legally hire someone without a license, so there is little incentive to actually become more productive. The only justification for preferring mandatory licensure over voluntary certification is if customers are incompetent at judging the quality of workers. There is an argument that most people cannot judge how good their doctor is, but rather than give one licensure organization a monopoly over medicine, it would be better for society if there were competition between multiple organizations that offered licenses because they would compete to demonstrate that their group is better quality than the other.

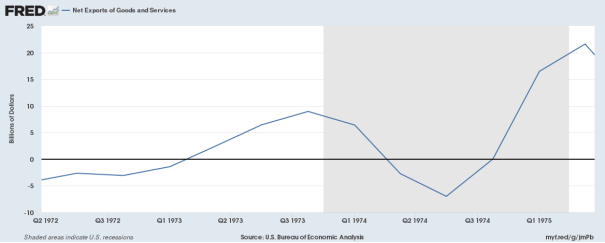

Then it happened again in 1979 due to the Iranian revolution shutting down its massive oil exports. Again, US oil imports dropped, prices rose and

Then it happened again in 1979 due to the Iranian revolution shutting down its massive oil exports. Again, US oil imports dropped, prices rose and